Christian history, sadly, has a great deal of anti-Semitism in it, and many great saints and theologians, Christian history, sadly, has a great deal of anti-Semitism in it, and many great saints and theologians, who otherwise should have known better, fell for Anti-Semitic tropes, helping to preserve them for future generations. When they did so, they are not to be commended. We need to be realistic about them, and understand that they were fallible men and women who, though filled with grace, and who did some great things through the grace they were given, still could and often did many terrible things which later Christians would have to fix. Holding onto tradition, looking to the past to learn from what was known and accepted, to how things were done, does not mean we should just embrace everything we find uncritically. There are many things which were done that we now know were wrong (among which, of course, is slavery). The most important thing we learn from the past is the way God is always at work with humanity, and humanity is always wrestling with – and learning from – the way God works with them. Things change. Our knowledge and understanding develops and changes. We are able to speak of things in ways the earliest Christians could not; we would be wrong to go back to the ambiguity of the ante-Nicene age in regards the Trinity. Thus, Christians need to realize holding onto tradition does not mean holding to all the beliefs and practices of the past, but rather, it is about sifting through it, taking the good while discarding, and indeed criticizing the bad. If we don’t, then, as Marsilio Ficino said, traditionalism can become a dangerous trap which leads us astray: “Furthermore, ancestral custom and time-honoured tradition easily trap everyone in any error whatsoever.”[1]

When we look back, and see something which was done, many of us will say that we must continue and do exactly the same, because we believe what was done in the past must be seen as a good, not realizing that in every generation, Christians will do both good and bad. Thus, while we must not assume everything was bad in the past, indeed we must acknowledge holy tradition exists and is to be followed, we must not assume everything which was done in the past was actually for the good, nor actually was a part of holy tradition. Rumors, gossip, speculations, and the like often have people think and act in certain ways, which, once explored and shown to be false, will lead them to be embarrassed. This is especially true in regards Anti-Semitism. It is based upon all kinds of falsehoods. It has been used to justify all kinds of great evils. And, Christians, looking back, should feel ashamed for its presence in Christian history.

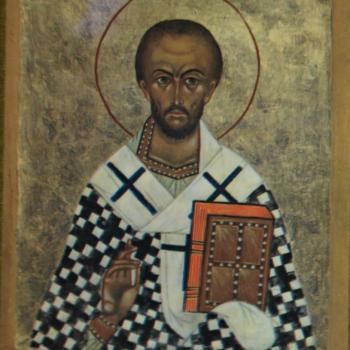

Sadly, many so-called traditionalists (who embrace only a narrow slice of the past, and create, with it, a false vision of it and therefore, of tradition), see the hostility many Christians had against the Jews, and embrace it as a part of holy tradition, demanding, therefore, others to do likewise. They are right in pointing out how wide-spread it was, and they certainly can show us the terrible words spoken by otherwise great men like St. John Chrysostom (or Marsilio Ficino himself), but the spirit of such Anti-Semitism has always gone against the preaching of Christ and the Apostles. Paul consistently spoke in favor of the Jews and reminded converts not to be disdainful of them. Following tradition, however, requires us to do more than repeating what others did in the past, for it requires us to sift through such practices, to purify them, and to embrace and pass on, not everything we find from the past, but only what is good and true, what is holy and just. Tradition is living, and therefore in constant development, casting away the chaff of the past; if not, then all we will have is new wine (the world as it is today) being put in old wineskins which cannot take the new wine. Jesus wanted his followers to understand the error of this, which is why he said:

He told them a parable also: “No one tears a piece from a new garment and puts it upon an old garment; if he does, he will tear the new, and the piece from the new will not match the old. And no one puts new wine into old wineskins; if he does, the new wine will burst the skins and it will be spilled, and the skins will be destroyed” (Lk. 5:36-37 RSV).

Wine, it can be said, represents tradition. New wine is the way tradition is embraced in the current age. The wineskins are the beliefs and practices in which tradition is to be found. We are given new wine, and so we are to use new wineskins, that is, those practices which fit for the new wine we have been given. In regards Anti-Semitism, this means, we must entirely denounce it as evil, looking back to the way it came about, so that we can overcome its causes, but also rejecting the evil which it caused, evil which eventually came to the head with pogroms and the Holocaust in the modern age. Nostra Aetate rightfully tells Christians to undergo metanoia, to repent of the evils they have done to others. Bigotry must be abandoned. The other must not be criticized just because they are different.

The Church reproves, as foreign to the mind of Christ, any discrimination against men or harassment of them because of their race, color, condition of life, or religion. On the contrary, following in the footsteps of the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, this sacred synod ardently implores the Christian faithful to “maintain good fellowship among the nations” (1 Peter 2:12), and, if possible, to live for their part in peace with all men,so that they may truly be sons of the Father who is in heaven. [2]

We must not assume the reason why others don’t believe as we do is because they are willfully ignorant or evil. This, assumption, sadly, is what has caused Christians to treat Jews and Muslims with contempt. Nostra Aetate tells us to consider our own actions, our own ignorance of the other, our own ignorance of their beliefs and practices (and with it, therefore, the false assumptions and polemical treatises made based upon such ignorance), and see how this has caused pain and confusion in the world. To fix the problems we have caused, we must seek to know others better, to appreciate them and show them the love and respect they should have (even as we want it from them). Thus, in regards Muslims, we are told:

Since in the course of centuries not a few quarrels and hostilities have arisen between Christians and Moslems, this sacred synod urges all to forget the past and to work sincerely for mutual understanding and to preserve as well as to promote together for the benefit of all mankind social justice and moral welfare, as well as peace and freedom. [3]

This is also true indeed, especially true in regards to Christian relations with the Jews. We need to move past all our hostility, all the hatred and Anti-Semitic rhetoric found in the Christian tradition, call it out for what it is, so that we not only discard it, we work to repair the harm it has caused. We should repent and make satisfaction for the crimes against humanity our Anti-Semitism brought into being. Then, we can and should work to promote mutual respect and love with the Jews. Again, it becomes vital that we condemn Christian Anti-Semitism, even when it comes from otherwise great men and women of the church; their greatness does not make everything they believed or thought correct. When we can see our own great saints and thinkers doing wrong, and needing correction, we can begin to purify ourselves, and learn from them, not what we should be like, but what it is we must repudiate and correct in ourselves. And so, Christians need to learn from the Jews, just as they need to learn from Muslims:

Since the spiritual patrimony common to Christians and Jews is thus so great, this sacred synod wants to foster and recommend that mutual understanding and respect which is the fruit, above all, of biblical and theological studies as well as of fraternal dialogues. [4]

We need to be humble. We need to acknowledge our sins, and see among them, some of the greatest sins of Christianity lay with Anti-Semitism and the justifications it gave for abusing the Jewish people. Triumphalism suggested that the Christian faith should be easily seen as true by everyone, and so assumed the worst by those who didn’t become Christian. Ficino’s vile take on the Jews represents a common belief and approach which developed within Christendom:

But the Jews have been given over to avarice, usury, lies, and sin. And they themselves even grant that it is because of their sins that they live in this misery, and compelled by the authority of Deuteronomy, they admit that if, after giving up their depravity, they are converted to God, they would be delivered forthwith. [5]

Ficino, who should have known better himself, shows how easy one can be led astray and find it hard to see through the ignorance one has come to believe represents knowledge and truth. But we, who have learned more, and have seen through such ignorance, now have the responsibility to repudiate it. This is what Nostra Aetate has done, showing that we cannot and must not blame the Jewish people for what a few had done:

True, the Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ; still, what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today. Although the Church is the new people of God, the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures. All should see to it, then, that in catechetical work or in the preaching of the word of God they do not teach anything that does not conform to the truth of the Gospel and the spirit of Christ. [6]

We cannot ignore the past, and the Anti-Semitism found in the Christian tradition. We must point it out, acknowledge it, and repudiate it. This does not mean we can and should abandon the whole of the Christian tradition, for that would lead to the same mistake which led to Anti-Semitism. We should acknowledge, rather, the way people can be complicated, personally and communally, and that those who do good in one area, can and should be acknowledged for that good (such as St John Chrysostom’s work to promote notions of social justice), while they can and did much which was bad or evil in another (as Chrysostom, Ficino, Chesterton, and so many others showed in the way they embraced Anti-Semitism). If we want to appreciate them for the good they have done, we must also acknowledge that evil, otherwise, we will hinder the good because others will see the evil and associate all that they have done as being equally evil. When we look to the past, then, as Ficino said, we must not let our embrace of tradition allow the evil of the past to trap us in continuing that evil today. In regards Anti-Semitism, we must note it whenever we find it, realizing there are many kinds and levels of Anti-Semitism in Christian history, even as there are many kinds of it among us today. All need to be repudiated, though the difference between them acknowledged. We must do what we can to counter its re-emergence, and we must make amends for it, not only for what was done in the past, but what is currently being done in the name of Christ today. We can’t let Anti-Semitism continue. It must be repudiated. Anti-Semitism is an evil, and one which if embraced, will only lead everyone back down the path to hell, the path of the Holocaust. We can’t let that happen again,

[1] Marsilio Ficino, On the Christian Religion. Trans. Dan Attrell, Brett Bartlett, and David Prreca (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022), 219.

[2] Nostra Aetate. Vatican translation. ¶5.

[3] Nostra Aetate, ¶3.

[4] Nostra Aetate, ¶4.

[5] Marsilio Ficino, On the Christian Religion.145.

[6] Nostra Aetate. Vatican translation. ¶4.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!