One of the many intriguing stories in Genesis is that of Jacob dreaming about a ladder which went up to heaven:

Jacob left Beersheba, and went toward Haran. And he came to a certain place, and stayed there that night, because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones of the place, he put it under his head and lay down in that place to sleep. And he dreamed that there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it! And behold, the LORD stood above it and said, “I am the LORD, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac; the land on which you lie I will give to you and to your descendants; and your descendants shall be like the dust of the earth, and you shall spread abroad to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south; and by you and your descendants shall all the families of the earth bless themselves. Behold, I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done that of which I have spoken to you.”

Then Jacob awoke from his sleep and said, “Surely the LORD is in this place; and I did not know it” (Gen. 28:10 – 16 RSV).

It was commonly believed that God could and often did communicate with people through dreams; indeed, dreams were one of the ways prophets got in touch with the transcendental reality of God. Through his dream, whether or not it was directly given to him by God, or his mind working with the presence of God which he encountered at the place he was at before he went to sleep, Jacob perceived that heaven and earth were connected together as if by a ladder. Then, he received a message from God concerning the blessings which God had promised to Abraham.

There are many ways this story can be interpreted, and each of them can complement each other. This is because each passage of Scripture has many meanings implied at the same time. Of course, we do not have to agree with all possible interpretations; it is not a free for all. But we are free to accept those which we believe are applicable, so long as they connect with and continue to present the Christian faith (and not contradict it).

The simplest meaning for the story is the one which suggests that God granted Jacob an understanding of the future glory of the people of Israel and the land in which they would dwell. The historical legacy of the people of Israel, and their residence in the land of Israel, represents ways in which God kept his promise to Abraham.

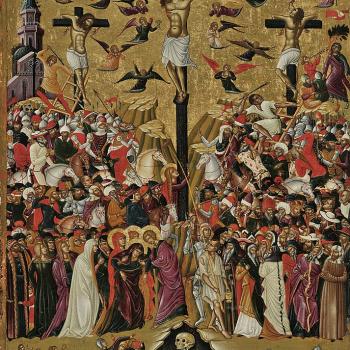

Nonetheless, there are other interpretations which can be had with this verse (even as there are other, complementary interpretations of God’s promise to Abraham). Christian commentators suggest that all the talk of Israel, all the talk of the descendants of Jacob, all the talk of the land, also represents the glory which Christ’s resurrection brings to the world. The incarnation especially fulfills God’s promise to Abraham. Through Jesus, everyone is called to share in that promise, to become heirs of God’s promise to Abraham. Thus, some, like St. Chromatius of Aquileia, would suggest that Jacob’s Ladder is itself a foreshadowing of the Cross, the ladder which all the adopted children of God can use to climb up to heaven:

Therefore, the way is opened by Christ’s resurrection. Hence it is not without reason that the patriarch Jacob related that he saw a ladder in that place [see Gen 28:16] whose top reached to heaven, and the Lord was leaning upon it. The ladder fixed from earth to the heaven [see Gen 28:13 LXX] is the Cross by which there is a place for us in heaven that truly reaches up to heaven. On this ladder many steps of virtue have been inserted by means of which the stages of our ascent to heaven consist: faith, justice, modestly, holiness, patience, piety, and the other goods of the virtues [see Gal 5:22-23] – these are the rungs of this ladder. If we faithfully ascend by means of them, doubtless we shall reach heaven.[1]

St. Irenaeus, likewise, sees the tree of life, the Cross, indicated by Jacob’s Ladder:

Jacob also, while journeying into Mesopotamia, sees Him, in a dream, standing at the ladder, that is, the tree, set up from “earth even to heaven”; for by it those who believe in Him mount to heaven, for His passion is our raising on high. [2]

Important to St. Chromatius is the relationship between the Cross and the Two Testaments, which means we must not deny the value of the Tanakh and the traditions surrounding it:

Now it is right for us to recognize that the ladder signifies the cross of Christ, since just as a ladder is held together by two beams, so too the cross of Christ is held together by the two testaments, containing between them the rungs of the heavenly precepts by which ascent is made to heaven. [3]

Jacob’s Ladder, the way which leads up to heaven, the way which heaven and earth is connected, the way which angels are found to travel to and from the earth, is remembered during the time of Lent in the Byzantine Calendar by the commemoration of St. John Climacus on the Fourth Sunday of the Great Fast. He is famous for his text, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, which borrows from the image of Jacob’s Ladder, suggesting that the path to heaven is like a ladder with many rungs. Because the book was written primarily for monks, and so often discusses practices suitable only for a monastic community, the text often needs to be read with prudence, with the realization that many of its practices need not, or should not, be acted upon by the ordinary reader. Nonetheless, with that caveat, one can sift through the book and find wisdom applicable by all, making it and its author worthy of being honored during Lent.

Indeed, it is important to point out that John Climacus began his work with a note that God loves all, and is working to save everyone; he did not want to suggest only those who had a monastic vocation, or those who followed an extreme ascetic discipline, would be saved:

God is the life of all free beings. He is the salvation of all, of believers or unbelievers, of the just or the unjust, of the pious or the impious, of those freedom from the passions or caught up in them, of monks or those living in the world, of the educated or the illiterate, of the healthy or the sick, of the young or the very old. He is like the outpouring of light, the glimpse of the sun, or the changes of the weather, which are the same for everyone without exception.[4]

In this passage, we get a sense of Climacus’ Christian foundation. He understood God’s saving grace was at the center of our salvation. God is working to save everyone. Even those who are unbelieving sinners can be saved by him. This is not to say those who need to be reformed should not reform themselves; rather, God’s love is so great, he sends his saving grace out to all, and so those who people perceive as far from God can still be called by him, change their ways, and be saved.

Climacus’ analogy to the sun is very appropriate because it connects with the way Jesus himself is seen as the sun of righteousness (cf. Mal 4:2). Just as the sun shines on all, so God shares his grace with all. This, of course, helps us to realize that God is working for all of us; once we realize this, we have reason to have hope and never fall into despair. Likewise, because it is God who is at work and his grace which perfects us, we must avoid all sense of vainglory, for such vainglory gets us away from the grace of God. Thus, seeing the similarity and difference between despair and vainglory, St. John writes:

The spirit of despair exults at the sight of mounting vice, the spirit of vainglory at the sight of the growing treasures of virtue. The door for the one is a mass of wounds, while the gateway for the other is the wealth of hard work done.[5]

God established the means of our salvation. He opened up the path to heaven. His grace perfects us so we should not despair when we falter, but because it is his grace which does the greater work (and not us, though we must cooperate with it), we should not pursue works of virtue as a way to glorify ourselves. All glory is from God, through God, and with God.

Even though it is God who does the major lifting and has set up the “ladder” to heaven, we still need to climb the rungs, which, like St. Chromatius, St. John says is connected with the virtues:

The holy virtues are like the ladder of Jacob and the unholy vices are like the chains that fell off the chief apostle Peter. The virtues lead from one to another and carry heavenward the man who chooses them. Vices on the other hand beget and stifle one another. [6]

Our vices, our sins hold us back, like the chains of St. Peter. We must struggle to get free, to pursue the virtues and gain the strength which they bring us. We must not despair once we get caught in some sin, but rather, we must once again return to the practice of the virtues, and let the grace of God help us as we grow in virtue and so climb up, as it were, the rungs of the ladder which lead us to heaven.

Not everyone is expected to pursue the holy life in the same way. The spiritual life cannot be and should not be reduced to one form, even if the principles (the virtues) behind the spiritual life remain the same. We must find what way of life we are to live, and follow through with it: “The real servants of Christ, using the help of spiritual fathers and also their own self-understanding, will make every effort to select a place, a way of life, an abode, and the exercises that suit them.” [7] Some will be monks and nuns, some will be priests, but most will find their way of life is in secular society; they will have to pursue the virtues in society and not apart from it. But everyone must seek God where they are at, and pursue God with the greatest virtue of all: love. For it is love which overcomes evil: “Love is the banishment of every sort of contrariness, for love thinks no evil.”[8]

If we want to grow in virtue, we must fight against their contraries, the vices. Thus, charity helps us overcome avarice. And we must take extra concern with avarice, for the love of money is the root of all evils. Avarice distracts us with an idol which it puts in our way: “Avarice is a worship of idols and is the offspring of unbelief. It makes excuses for infirmity and is the mouthpiece of old age. It is the prophet of hunger, and the herald of drought.”[9] For this reason, those who pursue wealth, ignoring and contending against the proper distribution of goods by hoarding material possessions for themselves, find themselves going against the Gospel: “The miser sneers at the gospel and is a deliberate transgressor. The man of charity spreads his money about him, but the man who claims to possess both charity and money is a self-deceived fool. “[10]

What we seek is not mere entry into heaven, but union with God and the theosis which follows. For us to attain this union, we must learn how to detach ourselves from all things which keep us apart from God. This is not because we should nihilistically reject them, but rather, because we should first seek God and then all things will be given over to us once we find ourselves joined together with him. Once we have experienced such unity with God, we will be able to understand what God has said and done and why he has done so. Until then, we must be humble about what we say, knowing that we talk about God and the truths of God with great difficulty: “When a man’s senses are perfectly united with God, then what God has said is somehow mysteriously clarified. But where there is no union of this kind, then it is extremely difficult to speak about God.”[11]

Only when we are united with God and see and know all things in and through the light of God’s grace, will we see things as they are; we can become attracted and fascinated with things in the way they appear to us apart from the light of God’s grace, and that is how they can divert us from the glory which we are meant to attain and receive. This is why detachment is important: it is not about denying any created good, rather, it is about receiving it in its proper form and rejoicing in it as it is revealed in the glory of God.

We will one day die, and we will not be able to keep the things we have in the way we have them after death. We will feel pain and sorrow from the detachment which must come about in our death if we have not yet found a way to cut off all attachments before we die; this is why we must “die” to the world, so that before our death we already experience such detachment. Otherwise, at the point of death, we will be addicted to and attached to the things of the world, suffering in accordance to the level of attachment we have with them when we leave them behind at death. And so, “The man who has died to all things remembers death, but whoever hold some ties with the world will not cease plotting against himself.”[12]

The ladder to heaven, the Cross, requires us to embrace all that the Cross means so that through it we can die to the self and find ourselves resurrected in Christ. We should pursue the glory of God, not by abandoning care or concern for others, but by abandoning our unhealthy way of engaging the world. We must come to know ourselves, know where we falter from grace, so that we know what needs to be done. Them, we can slowly grow in virtue until, at last, we find ourselves shining with the glory of the kingdom of God, capable of sharing that grace with others:

Among beginners, discernment is real self-knowledge; among those midway along the road to perfection, it is a spiritual capacity to distinguish unfailingly between what is truly good and what in nature is opposed to the good; among the perfect, it is a knowledge resulting from divine illumination, which with its lamp can light up what is dark in others. [13]

The Great Fast reminds us of our spiritual quest. The Ladder of Divine Ascent represents one way in which that quest has been mapped out for us. It is written for monks, and so, since not everyone is called to the ascetic life, not everyone is expected to follow all of its contents. But it contains wisdom and lessons which we can all reflect upon and employ in our own life. It reminds of the value of discipline for the spiritual life even as it warns us of various spiritual traps which can stop us from our pursuit of heaven. It represents the way of the Cross, and with it, the dying to the self we all need before we can experience the full glory of the resurrection to come.

[1] St. Chromatius of Aquileia, Sermons and Tractates on Matthew. Trans. Thomas P. Scheck (New York: Newman Press, 2018), 19 [Sermon 1].

[2] St. Irenaeus, Proof of the Apostolic Teaching. Trans. Joseph P. Smith, SJ (New York: Newman Press, 1952), 77.

[3] St. Chromatius of Aquileia, Sermons and Tractates on Matthew, 19 -20 [Sermon 1].

[4] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 74.

[5] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 202.

[6] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 152.

[7] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 79.

[8] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 286.

[9] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 187.

[10] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 187.

[11] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 288.

[12] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 135.

[13] St. John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 229.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!