Paul tells us to look at the God-man in the incarnation, to contemplate his kenosis, and to use what we see as an example for how we should love: “Have this mind among yourselves, which was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men” (Philip. 2:5-7 RSV).

Jesus, the God-man, did not attach himself to his divinity in such a way as to ignore his humanity; rather, he emptied himself, detaching himself from an exclusive engagement with his divinity, so that he could engage creation with his love. This is not to say he no longer was God: he was, and he will always be God. This is not to say he no longer experienced the divine life: he did, but he did not find himself holding to it in exclusivity. His human consciousness, his human mind, experienced the divine life thanks to the hypostatic union, realizing the divine life is the life of love. He lived out that experience by being in the world and working for the salvation of all within it. He did not remain secluded from the world; he took the divine experience with him in all that he did, showing that there need not be any distinction between that experience and his activity in the world. Indeed, if we are careful and pay attention, Jesus consistently showed us that the two go together as one.

If we experience some great mystical experience, if we are lifted up by grace, we should not be attached to the experience, seeking after it in such a way as to have it separate us from the world. We must not retreat from the world in that way. Such a gnostic denial of creation opposes the intention of the incarnation. Rather, we are to take that experience with us, indeed, to find a way to have it always with us while we go out in the world, working the work of Christ in the world, seeking to make it a better place, offering it Christ’s grace. We must avoid self-attachment, where we become so self-absorbed, we ignore the world around us. When we die to the self, when we overcome those attachments which would lead us to close ourselves off from the world, we do not lose the grace which we have received, but rather, we let its effects grow, in us and in the world, so that we do not become stuck in a certain position but rather find ourselves engaging perpetual theosis.

This is not to say there will be no time for us to go on some sort of retreat from the world, but we must remember, we do so to rest, to prepare ourselves for our greater work in and for the world. Jesus, at the beginning of his mission, went into the desert to fast and pray, showing us that we, too, can and should make a time of purification and preparation for ourselves so that we can be open to the grace of God in our lives. We must silence ourselves so we can experience the presence of God. It is there. It is always there with us. What we need to do is find the way to experience it. And this is what such times of purification are about; they allow us to empty ourselves and divest ourselves from all distractions, so that once our undue attachments are set aside, we not only become aware of the presence of God, we will be ready to listen to and follow what God is willing to reveal to us when we experience his presence in our lives. We must learn to deny ourselves, to overcome the inordinate habits of concupiscence; once we have done so, we can learn to live in a radical state of love, a state in which we will always find the experience of God is with us wherever we shall go.

When we begin to experience the glory of God in our lives, and we see some sort of great miracle or blessing coming from it, the worst thing to do is become attached to what experienced, for then we become prideful, and through that pride, become attached to ourselves, losing our proper relationship with God. So many people get lost in spiritual delusion because they allow pride to develop as a result of their spiritual experiences. We must truly learn the way forward is further detachment, further kenosis, so that such pride cannot take root. Once we have learned this lesson, we can truly begin our walk with God. Then we will know that we must follow him wherever he should lead, and that often means, into the world, to be with people, doing what we can to help them instead of being concerned solely on our own private good. If we truly have emptied ourselves of ourselves, we will love others, and in that loving of others, we will find we will not lose our connection with God.

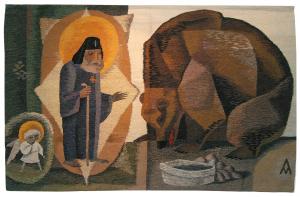

Thus, even great, ascetic saints, great hermits, find themselves challenged to be in the world, working for the benefit of the world; once they have overcome that challenge, their lives become one of constant intercession with God, integrating their experience of God with their actions, so that all they do works to share God’s grace to the world. Likewise, they find themselves often called outside of their retreat from the world, to be in the world, to speak and act from their experience of God, and because their experience is not based upon their retreat from the world but rather what they learned in that retreat, they could and would go into the world, acting on its behalf. St. Anthony the Great left his cell to go into the world to help the confessors and martyrs of the faith, and later, he would do so again to go to Alexandria and help Athanasius in his fight against the Arians. Likewise, St. Seraphim of Sarov, after he found that he truly had acquired the Holy Spirit in his life, knew he could not stay in a retreat from others, and so he opened himself to others so that he could share God’s grace with them:

After five years of this seclusion within the Monastery, St. Seraphim, by a special revelation, opened the door of his cell for all who desired to see him; but still he continued his spiritual exercises without paying any attention to his visitors or answering their questions. After five more years the Mother of God again appeared to him, together with Sts. Onuphrius the Great and Peter of Mt. Athos, instructing him to end his silence and speak for the benefit of others. Now he greets all who came with a prostration, a kiss and the Paschal greeting: “Christ is risen!” Everyone he called “my joy.” In 1825, the Mother of God again appeared to him and blessed him to return to his forest cell.

For the last eight years of his life St. Seraphim lived in the forest of Sarov and received the thousands of pilgrims who came to him to ask his prayers and spiritual counsel.[1]

Nicholas Motovilov was one of those who was welcomed by St. Seraphim, and when he did, he found himself partaking of the vision and experience which St. Seraphim experienced, seeing all things in and through the grace of the Holy Spirit. This was possible once St. Seraphim of Sarov had reached his final stage of spiritual development, when he moved from his seclusion to being open to the presence of others in his life. He found his experience of God not only continued once he moved out of seclusion, but it was something he could share with others, helping them receive, at least in part, the experience which he had experienced, sharing the grace which he had attained so that their lives could be and would be changed. He learned that the final stage is to follow the pattern of the self-emptying of Christ, to divest himself of himself by being with others, and in that way, to truly experience how God makes heaven and earth one.

Jesus, being God and man, continued to experience the glory of his eternity, even in the self-emptying of the incarnation. He shows us that divesting ourselves of ourselves is the proper way to live and thrive. Novices in the spiritual life often get caught up in various experience they have. They need to resist the temptation to hold onto what little they have experienced, making the beginning of their spiritual journey their end. They must not attach themselves to it lest they get caught up in themselves and cut themselves off from God in their pride. This temptation is normal. We see even Peter, James, and John, when they experienced the glory of the transfigured Christ, fell for it, and it was thanks to the guidance which they received and accepted, that they were able to see past the moment and detach themselves from it and leave Mt. Tabor behind. They did not lose what they experienced; rather, by detaching themselves from it, they were able to have the experience continue on with them, to grow with them, so that they finally were able to understand that what they experienced on Mt. Tabor is something they could and would experience everywhere they should go.

This is what we must also learn. We must not try to reify the moment we are in and be stuck in it. We must detach ourselves from it, no matter how great it seems, and when we do, then we are on our way to finding the kingdom of God, realizing it is all around us. What we thought was great will be revealed as nothing in comparison to what we can and will have when we live through true detachment. This means, working for the good of the people of the world, far from diverting us from our spiritual profession, is a part of it. This, again, is what God shows us in the incarnation. He loved the world. The Logos assumed human nature to be in and with the world. He did not ignore the world, he did not to ignore the pain and sorrow of the people of the world; rather, he came to help us all, healing us both in soul and in body. We cannot ignore the suffering of others and think we are truly following the way of Christ. There are, of course, different ways we can be called to work for others. But what must be understood and accepted is that we should seek to make thing better, not just for ourselves, but for all, so that we end up sharing the grace of God with the world, healing it from the defacement of sin. This is why, if we imply the work for social justice, the work for the betterment of the world, is in some way contrary to the spiritual life, we only show ourselves to be like the so-called gnostics of the past, and far from the full realization of the Christian faith. So long as we are attached to ourselves and our own spiritual experiences, seeking to increase them while ignoring the plight of others, we are far from the path of Christ and those experiences are in vain.

[1] Little Russian Philokalia. Volume I: St. Seraphim. Ed. and Trans. Seraphim Rose (New Valaam Monastery, Alaska: St. Herman’s Press, 1991), 19.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!