Sometimes, what is good and useful for a time must be put aside, not because it was never good, but because people have come to abuse the good, using it in a way which runs contrary to its original intention so that it no longer serves the good it once promoted. That abuse can actually turn the good thing into an idol, and those who promote it end up no longer promoting the good originally intended by it but some form of idolatry which has later formed in relation to it. This is what happened to the bronze serpent which Moses made. At its inception, it served as a tool for God to work wonders:

From Mount Hor they set out by the way to the Red Sea, to go around the land of Edom; and the people became impatient on the way. And the people spoke against God and against Moses, “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we loathe this worthless food.” Then the LORD sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. And the people came to Moses, and said, “We have sinned, for we have spoken against the LORD and against you; pray to the LORD, that he take away the serpents from us.” So Moses prayed for the people. And the LORD said to Moses, “Make a fiery serpent, and set it on a pole; and every one who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.” So Moses made a bronze serpent, and set it on a pole; and if a serpent bit any man, he would look at the bronze serpent and live (Num. 21:4-9 RSV).

The bronze serpent and the pole were preserved as holy relics. Great miracles, it would seem, continued to happen in and through their presence. They served as signs of God’s grace to the people of Israel. But slowly, though time, people began to misconstrue the serpent, ignoring its original signification as they turned it into an idol. While not everyone did so, and so it is likely some people were able to receive the benefit originally intended to be granted through it, enough people turned it into an idol so that it had to be destroyed:

In the third year of Hoshea son of Elah, king of Israel, Hezekiah the son of Ahaz, king of Judah, began to reign. He was twenty-five years old when he began to reign, and he reigned twenty-nine years in Jerusalem. His mother’s name was Abi the daughter of Zechariah.

And he did what was right in the eyes of the LORD, according to all that David his father had done He removed the high places, and broke the pillars, and cut down the Asherah. And he broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the people of Israel had burned incense to it; it was called Nehushtan. (2 King 18:1-4 RSV).

The idolization of the Nehushtan shows us what often happens in religion; some good becomes misunderstood and confused as being a higher good than it is, causing people to misconstrue the actual good (with the worst case scenario being the object in question becomes confused with the highest good, and in this manner, it is turned into an idol and used by people to turn away from the absolute good of God). When this happens, havoc follows. The teachings of the religious tradition in question are mutated and turned against themselves. Everything is read in and through the distorted understanding of the good, meaning the truth itself becomes rejected for some simulacra of it. Religious authorities will then have to deal with the problem at hand; if they can correct people’s mistaken views, they will do so, but if they find the cult around the particular good does not allow correction, then those leaders will have to take direct action against such abuse, even if it means discontinuing or dismantling the good which once was there.

We are to worship God in spirit and in truth, but we are also to do so with love, love for God as well as love for our neighbor. If particular religious practices get in the way of the law of love, if we begin to regard such practices as being more important than the truth and good which is meant to be represented by them, then we must not be surprised if some correction is made, some reform is had, which can include the elimination of particular forms of worship if and when they have become abused. If someone were to assert only one liturgical tradition is valid, and within that tradition, only one form of it can be followed, it is clear they have gone beyond the truth and have turned their liturgical preference into an idol. At such a time, the church needs to act; if such liturgical idolatry is followed by a large number of people who are militant in their idolatry, the church might have to follow the example of Hezekiah and do away with the liturgical form in question. This does not mean the church denies the historical value of that liturgical form, nor say that only the forms which exist today are what the church will ever permit, but instead, the church will act in relation to the times, dealing with the situation it finds itself in, so that what once was permitted might for a time have to be put to stop, or what once was stopped might one day be put to use once again (do we not see the latter in the restoration of the permanent diaconate?).

Liturgy is important, but we must understand, it has constantly been under development, and no liturgical tradition has been without change. Each tradition was originally created to meet the needs of particular peoples, to help make sure they can come together as one and partake of the blessings of God. They can be and are quite remarkable in their ability to do this, though it must be understood, they are not of much value in and of themselves, but rather it is the grace which God grants to them, the grace which brings various gifts like the sacraments to the people, which truly make such liturgies invaluable. That we see a diversity of rites and traditions shows that there is no one form which needs to be put in practice in order to receive these gifts. Liturgy must not be understood as mere magical incarnations which will no longer have validity if the rites are changed; the validity comes not through the words, but through the Holy Spirit (which is why some rites rely upon the Spirit more than the words themselves). Those who get confused and think it is about the liturgical rites and repeating exactly specific words and phrases do not truly understand liturgy; it is, indeed, this ignorance which leads so many people to idolize a particular form of the liturgy and think it must be done in one exact way for it to be valid. Such idolatry of a particular liturgical form is dangerous, because it leads to an impoverished, indeed, potentially dead faith, as it confuses liturgical practice with the faith itself.

It was such confusion, perhaps, which led to the important declaration:

The sacred liturgy does not exhaust the entire activity of the Church. Before men can come to the liturgy they must be called to faith and to conversion: “How then are they to call upon him in whom they have not yet believed? But how are they to believe him whom they have not heard? And how are they to hear if no one preaches? And how are men to preach unless they be sent?” (Rom. 10:14-15).[1]

Liturgy is important, but it is a part of a greater whole. Liturgy is a way for us to express our faith, to engage God, and receive the gifts of God, but there are other ways for us to do this as well. Yes, it can be said to be the summit of our earthly activity, especially because through it, we are called to communion and receive the eucharist, but we must remember, that as the summit, it includes and presupposes the rest of the faith and its practices. Moreover, what makes it the summit must be clear, it is the eucharist and the sacramental gifts we receive, not, however, the form of the liturgy itself, which is why the liturgy can come in many forms:

Even in the liturgy, the Church has no wish to impose a rigid uniformity in matters which do not implicate the faith or the good of the whole community; rather does she respect and foster the genius and talents of the various races and peoples. Anything in these peoples’ way of life which is not indissolubly bound up with superstition and error she studies with sympathy and, if possible, preserves intact. Sometimes in fact she admits such things into the liturgy itself, so long as they harmonize with its true and authentic spirit. [2]

Thus, instead of enforcing one form of the liturgy, the church wants diversity. Such diversity allows the people to be what the church wants them to be, active participants in the liturgy. And because different people, different cultures, have different ways of being, this can mean there will be the need for radical differences in liturgical celebrations around the world, and when they are seen, they must not be assumed as being some sort of liturgical abuse:

In some places and circumstances, however, an even more radical adaptation of the liturgy is needed, and this entails greater difficulties. Wherefore:

1) The competent territorial ecclesiastical authority mentioned in Art. 22, 2, must, in this matter, carefully and prudently consider which elements from the traditions and culture of individual peoples might appropriately be admitted into divine worship. Adaptations which are judged to be useful or necessary should then be submitted to the Apostolic See, by whose consent they may be introduced.

2) To ensure that adaptations may be made with all the circumspection which they demand, the Apostolic See will grant power to this same territorial ecclesiastical authority to permit and to direct, as the case requires, the necessary preliminary experiments over a determined period of time among certain groups suited for the purpose.

3) Because liturgical laws often involve special difficulties with respect to adaptation, particularly in mission lands, men who are experts in these matters must be employed to formulate them. [3]

The notion that there should be only one liturgical form around the world, and to make it as if that is all the Christian (or Catholic) faith is about is to misconstrue the faith itself. This is why those who see things being different in other places as being some sort of diminishment of Catholicism are wrong. There are many ways to be Catholic, many ways to embrace Catholicism. There will certainly be things in common, and indeed, if one looks beyond the external differences, and to the core, one will find the diverse forms of liturgical celebration hold the same basic elements. Those who deny this by claiming one form of the liturgy is superior to all others, and so no other forms are permissible, end up creating an idol out of the liturgy, which is why they focus so much on the rites of the liturgy and not on the greater Christian faith, because they think the liturgy and its form is all they need to care about in their practice of the faith.

Tradition is meant to be living, going forward, meeting new needs as time goes by; those, however, with a dead, idolatrous faith like to trap us with the way things used to be, to turn the faith into a museum, as it were, where everything is unchanging because life has been taken away from it. Faith requires us to move forward, to be willing to change; pride, on the other hand, often gets in the way, as Pope Francis explained to the Curia at the end of 2021:

Yet, if our remembering is not to make us prisoners of the past, we need another verb: to give life, to “generate”. The humble – humble men or women – are those who are concerned not simply with the past, but also with the future, since they know how to look ahead, to spread their branches, remembering the past with gratitude. The humble give life, attract others and push onwards towards the unknown that lies ahead. The proud, on the other hand, simply repeat, grow rigid – rigidity is a perversion, a present-day perversion – and enclose themselves in that repetition, feeling certain about what they know and fearful of anything new because they cannot control it; they feel destabilized… because they have lost their memory. [4]

We can see this throughout history. Legalism develops as a result of people unwilling to deal with the troubles of the present by demanding things to return to the way they think things were in the past. It creates a past which did not really exist, and tries to force it upon the present (and the future). Whenever the church has found itself being fought by people who held to such rigidity, that is, such desire not to allow for the church to change to deal with the pastoral needs of the people, the church has had to respond, first with exhortation, and then, if that did not work, with authoritative rejection of such rigidity. The Novatians, with their unwillingness to promote mercy and grace. cut themselves off from that mercy and grace. Hus, and so many others in the late medieval and early renaissance eras of the church, saw problems in their own day, complaining about changes in liturgy and worship as one of the major causes of the problem instead of realizing it would be the way the problems could be solved. Nicholas of Cusa, in responding to various critics of his time who were upset with various liturgical changes which happened in Western history, explained that such changes represent the way Christ and the Spirit are at work:

Hence, even if today there is an interpretation by the Church of the same Gospel command differing from that of former times, nevertheless, the understanding now currently in use for the rule of the Church was inspired as befitting the times and should be accepted as the way of salvation. [5]

Pope Francis, therefore, is right in dealing with those who would circumvent the church’s work in the world by idolizing a particular form of the liturgy and using that idolization as way to contend against the ongoing mission and work of the church. The liturgy has always been in flux, and will continue to be in flux until the end of time; there has been no liturgical tradition which has gone unchanged. There have been and are several different liturgical traditions, each of value in and of themselves, but each, likewise, changing and developing over time. The current form of the Western liturgy is a part of that development; those who try to act like it was created ex nihilo because it differs from their own liturgical preferences, or because it is clear people were involved in that development, ignore that the liturgy they like also had people involved in its creation and promotion in the time in which it became normative (causing people to fight against those changes when they occurred). Moreover, many of them that the normative Western form as it is practiced in the church today follows came out of and is an authentic development of the greater Western tradition; it continues with the basic elements of that tradition, transforming them to meet the needs of the time in which we live. This is not to say we cannot like, or even prefer, some forms of the liturgy over another, but we must remember, doing so does not make them better or superior. When we try to turn our personal preferences into absolutes and ignore the moving of the Spirit in the times which we live in, our rigidity threatens to be turned into idolatry. “Certainly in this lies the beginning of all presumption: when individuals judge their own understanding of divine commands to be more conformed to the divine will than that of the universal Church.” [6] When that happens, not just with us, but with large groups of people, then we should not be surprised ecclesiastical authorities will take note and deal with the problem as necessary, including the abrogation of certain forms of the liturgy so long as they remain a major cause for idolatry. This is not to say things cannot and will not change in the future. The church, in its wisdom, often takes from its past, but it never does so without prudence, without transformation; if some older liturgical forms find their use once again allowed in the future, it will be done only after the idolization and misunderstanding concerning them have been removed, and that means, it will likely be through some adaptation of those forms, as there will be other elements which will likely be kept as a thing of the past.

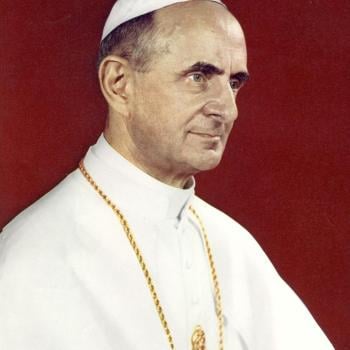

[1] Pope Paul VI. Sacrosanctum concilium. Vatican translation. ¶9.

[2] Pope Paul VI. Sacrosanctum concilium, ¶37.

[3] Pope Paul VI. Sacrosanctum concilium, ¶40

[4] Pope Francis, “Address to Roman Curia” (12-23-2021).

[5] Nicholas of Cusa, “To the Bohemians” in Nichola of Cusa: Writing on Church and Reform. Trans. Thomas M. Izbicki (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 23.

[6] Nicholas of Cusa, “To the Bohemians,” 17.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!