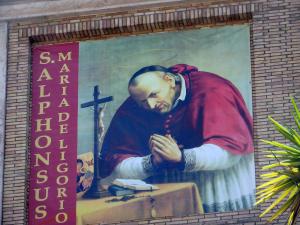

We have grown accustomed to accept the notion that ignorance of the law is not an excuse. The law is the law, and authorities have the power to enforce it, even upon people who had no way to know what the law expected them to do. Taken as an absolute, this would be unjust which is why, when we look to how ignorance is dealt in the judicial system, sometimes ignorance does become an excuse. If this were not the case, laws could be created with the express intention of keeping the public ignorant so that it became easy to punish them mercilessly. Laws made with such an intention would be unjust, and as such, could not be held obligatory as an unjust law is no law at all. The same, it can be said, with laws, which were not promulgated in such a way that they could be readily known by the public. Thus, ignorance sometimes can be and should be an excuse, otherwise, those with power can easily abuse their authority and turn the justice system upside-down. This is why it can be said that for a law to be valid, that is, for a law to hold some authority over the public, the public would need ample opportunity to know it exists. On the other hand, if someone were not to know about a particular law, and they did not know because they made sure they didn’t know what was or was not lawful, then they would be held culpable for their ignorance, and it is in such a situation, ignorance is not an excuse. Finally, if someone were not capable of knowing or understanding the law, such as those who have not reached the age of reason, they should be treated with mercy when they violate the law. This understanding of the law, and when ignorance could serve as an excuse, holds true, not just with civil law, but with natural law and eternal law, as St. Alphonsus Liguori explained in his discussion as to when one of those such laws could be seen as morally obligatory. He made the distinction between natural law and or eternal law because he thought we should not confuse what we find ourselves obligated to do or not to do under the natural law with the absolute truth of the divine law; instead, he saw that the natural law represented our best apprehension and participation of the divine law within particular contexts or situations.

Natural law is what we come to know of good and evil, of what is and is not expected of us, through our use of reason[1]. Insofar as we come to know something as good or evil, we must avoid the evil and embrace the good. Natural law, in this way, is a construction of the human mind, though one which is to be understood as influenced by the light of truth, that is the eternal law which transcends us. St. Alphonsus made it clear that the two are not to be equated because we are finite, temporal beings, looking to understand how we are to act in time and space; the eternal law, by its nature, transcends the natural law, transcends our limited, temporal existence, and so transcends our ability to understand it and its expectations. For this reason, the eternal law cannot be said to be obligatory to us, because its transcendence makes our ignorance of it a kind of invincible ignorance. In presenting this position, he took much from the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, especially in relation to the distinction between the eternal and natural laws, to show the distinction is not one which he himself made up but rather represents a long-standing theological understanding in the theological tradition:

St. Thomas, speaking on the eternal and natural law, teaches that to this end, that it could be a measure to us, it ought to be very certain and made known to us. Let us attend to the words of the Holy Doctor. He objects to himself, “A measure ought to be very certain (nota); but the eternal law is unknown to us; therefore, it cannot be the measure of our will that the good of our will would depend on it.” And so he responds, “Although the eternal law is unknown to us according to what is in the divine mind, nevertheless it is made known to us in some way through natural reason, which is derived from its own image, or is added from above through some revelation” (1.2. qu. 19, art. 4, ad 3). The reason is obvious why law ought to be certain; since law, according to the Holy Doctor, is a measure and a rule whereby a man is measured and ruled concerning certain actions; he can in no way be rightly measured and ruled unless the measure and rule were certain that it would oblige, that it would also be made known to man. [2]

While St. Alphonsus, therefore, pointed out the eternal law is beyond us, he also said we are not obligated to follow what the natural law can tell us to do if we do not have sufficient grounds or reason to establish those expectations, such as when we try to determine what we should do and yet find ourselves coming to an uncertain conclusion. This is because all laws, including the natural law, need to be given in such a way that they can be known by us. If we cannot determine what the natural law should lead us to do, it would not have been sufficiently promulgated, and so it would not be obligatory, just as any other law, which is not properly made known, allows ignorance to serve as a legitimate excuse. For, as he said, “If these principles the most certain is that A doubtful law cannot induce a certain moral obligation.” [3] St. Alphonsus suggested the promulgation of natural law comes through our reason, and what it is capable of determining from what it can and should know. This is why, for example, before the age of reason, no one is bound by the dictates of natural law, “Therefore, the natural law is not promulgated to man, nor does it bind him, except when a man attains to the use of reason, whereby the law is made know to him and promulgated.” [4]And this is why, when our reason cannot offer us an answer as to what is or is not to be done, or what can or cannot be done, a person cannot be said to be under any obligation, for they cannot be held culpable to what not been made clear to them. “Therefore, by no means does one sin when he scrutinizes the law with the hesitation of two equally probable opinions, and after applying due diligence, finds it altogether dubious and therefore not obliging.”[5]

We should seek to conform ourselves to the divine will, but that means, to doing what we understand to be good and just. We cannot conform ourselves to the divine will in the way God can, because we do not have God’s omniscience and omnipotence. Thus, if we are mistaken about what is good, we can be said to be conforming to God’s will if we do what we understand to be good, even as we would not be conforming to it if we act in such a way to reject that good. For it is seeking to do what is good which leads us to the good which is found in and with God’s will:

Therefore, St. Thomas teaches that when a man always wishes something for the sake of the good, he is already conformed to the divine will: but he is not in any way held to conform himself to the divine will in particular things that are unknown to him, and especially in precepts where this divine will has not been manifested. [6]

This is why, even if our understanding of the good is in error, we can be led by the pursuit of the good to the greater good, and by engaging that pursuit, be seen to conform ourselves to God’s will. Natural law is the best foundation we have to determine such good, which is why natural law is important. The expectations given to us by natural law are those which our reason demonstrates for us. But, we must remember, reason doesn’t produce such answers by itself; it gives us answers based upon what is given to it, and so the better we understand the world, and all that is in it, the more information and data our reason will be able to use to determine what should or should not be done. And so, it can be said that what we are obliged to do as a result of natural law will change, even as its obligations can differ from person to person.

Since what we find ourselves obligated to do changes, we have another reason to understand why the natural law must not be confused with the eternal, absolute truth. Instead, it should be seen for what it is, a relative truth which is derived from but is not the same as that eternal truth. Sadly, many try to conflate the two, confusing the truth which they apprehend with their reason with the absolute, transcendental truth, and in doing so, they absolutize the relative truth in such a way they undermine the absolute truth itself. They confuse their conventional understanding of the world as the absolute truth, and so they try to universalize what should not be universalize, trying to make, therefore, their own understanding obligatory on everyone else. Thus, it cannot be stated enough, the natural law must never be confused with the eternal law, just as in Christology, the human nature of Christ must never be confused with Christ’s divine nature. Once we understand this, we understand why we must not express the natural law in such a way as if it were the eternal law, nor must we try express the eternal law as if it were the natural law which is obligatory for us to follow:

Even so, I assert (and will clearly prove) that the eternal law, in respect to men, is not a proper law; for a proper law in regard to them is the natural law, which, although it participates in the eternal law, still it is that which properly binds men, since the natural law should only be promulgated to men and is applied by the light of reason. At least I saw (insofar as other theologians say) that the eternal law, although it has in itself the force to oblige in the first act, still was not a law actually obliging, and in the second act, until it was proposed, and through its understanding was applied to creatures; and thus I say emphatically it is taught by St. Thomas and by other theologians. [7]

So long as we try to make the transcendent law obligatory for us, we will demand what is impossible, for it represents the eternal activity and decisions of God, an activity which only God can and will do. Nonetheless, the conventional truth, what is obligatory to us through natural law, as it is determined by our reason, takes into consideration what is revealed to us from even the eternal law — revelation, and not just our experience, provides us our connection with the transcendent law in such a way as to make sure even our engagement of the natural law points us towards transcendence and not merely the natural law itself.

As we differ from each other even in our apprehensions of the truth, of the world around us, so our consciences will differ, meaning, what each of us is obligated to do through the natural law can be said to differ. This is not to say there will not be many common elements which are apprehended by us all, leading to common obligations by all; there will be such apprehensions, which is why we can establish various rights and laws based upon them. But even those principles which are held in common will be understood differently by different people, providing different expectations. When we properly understand this, we will better grasp the use and limits of the natural law. We will no longer consider it in a fundamentalistic, rigoristic fashion, the kind of engagement which, because it is no longer grounded upon reason but its similitude, has led many to question the very notion of natural law. For those questions come out of the way the natural law has been absolutized and universalized so as to confuse the natural law with the absolute, universal law which it cannot be. This shows us that what people question is not the principles behind the use and application of the natural law, but the abuse of the natural law which has bee confused with the natural law principle itself. Once that abuse is known and seen for what it is, the principles behind the natural law can and should once again be engaged, and as w will be taking in what we now know (such as has been revealed by the sciences) to help us in our moral reflections, we should not be surprised the conclusions we make today will differ from those of other ages.

[1] In this way, the conscience can be said to serve as the basis by which we know what the natural law expects for ourselves. For our conscience uses reason to establish its obligations: “Conscience is so defined: ‘It is a judgment, or practical command of reason, in which we judge something must be done here and now as a good, or something must be avoided as an evil.’ Moreover, conscience is called a practical command, in distinction from synderesis, which is the speculative knowledge of universal principles to live well, certainly: ‘That God must be worshiped, you do not do to another what you do not wish for yourself, etc.’, as St. Thomas holds, p.1, qu. 79, art. 12.,” St. Alphonsus Liguori, Moral Theology. Volume I: Books I – III On Conscience, Law, Sin and Virtue. Trans. Ryan Grant (Post Falls, ID: Mediatrix Press, 2017), 25.

[2] St. Alphonsus Liguori, Moral Theology. Volume I, 68-9.

[3] St. Alphonsus Liguori, Moral Theology. Volume I, 41.

[4] St. Alphonsus Liguori, Moral Theology. Volume I, 109

[5] St. Alphonsus Liguori, Moral Theology. Volume I, 115.

[6] St. Alphonsus Liguori, Moral Theology. Volume I, 72-3.

[7] St. Alphonsus Liguori, Moral Theology. Volume I, 98.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!