Our actions, more than our words, teach those around us. If our actions are uncharitable, we teach others to act similarly, and have no concern for others; if, on the other hand, we engage others with charity and grace, helping them as we can, we teach those around us, those who look up to us, to follow our example and care for others as well. It is easy to speak well, and to say what should be said, if we use the words of others. However, if we don’t put our words into action, even if the words are good, others will see how we ignore them and treat them as insignificant, and so they will see them as holding little to no true value. Some, of course, will look beyond the messenger and engage the words and live them out, but many, if not most, will not pay attention and just pay attention to what we actually do, and focus on that, imitating us and our actions. We can see this in the way many engage bishops; even if they speak good words, it is their actions which dictates what is seen as important. Those who want bishops to lead by example become more than a little perplexed when they see such bishops acting against the words they speak. Bede, in his commentary on James, therefore says if we are to teach, we should do so through works of charity and hospitality and other similar virtues:

For if anyone shows his neighbors the examples of good actions and turns them back to imitating the works of almsgiving or hospitality or of the other virtues which they had neglected, even though his tongue be silent, he actually executes the office of teacher and obtains from the devoted judge a sure reward in return for the salvation of his brother whom he has corrected.[1]

All Christians, as they are called to the universal priesthood in Christ, should be teaching by example. They should be ministers of grace, sharing the grace they have received with the rest of the world. Those we materially help, such as by giving them money, will not only be made physically better, but they will be spiritually nourished as they are taught by our deeds. The more we do this, the more we will find grace comes to us, allowing us, and not just those we help, to be saved. Scripture gives us several examples of this, such as Lot: “Call to mind Lot and you will discover that it was not the strangers who sought for him, but he who looked for strangers and this was pursuing hospitality.”[2] For Lot didn’t simply wait and help people who came to him, he went to the gates of the city, looking for people in need:

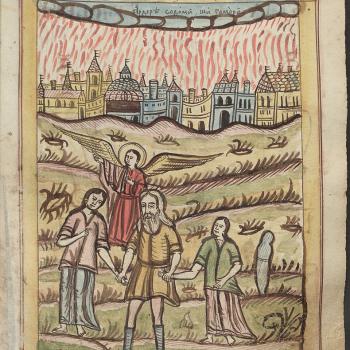

The two angels came to Sodom in the evening; and Lot was sitting in the gate of Sodom. When Lot saw them, he rose to meet them, and bowed himself with his face to the earth, and said, “My lords, turn aside, I pray you, to your servant’s house and spend the night, and wash your feet; then you may rise up early and go on your way.” They said, “No; we will spend the night in the street.” But he urged them strongly; so they turned aside to him and entered his house; and he made them a feast, and baked unleavened bread, and they ate (Gen. 19:1-3 RSV).

Lot was saved, and brought out of Sodom before its destruction, because he learned from Abraham the importance of charity. He was saved because he was a just, kind man who put others over himself, welcoming them as they should have been welcomed (while the rest of Sodom and Gomorrah ignored their duty, and so suffered the consequence of their evil deeds).

Monastic tradition is often filled with those saints, sometimes nameless (because many of them wanted to be nameless), who did more than merely follow ascetic discipline, but who showed the world what it was to be a Christian by engaging great acts of charity and love. Monasticism must not be seen as some sort of quietist retreat from the world, but rather, a discipline which helps people develop themselves and their natural goodness. That is, they are to find their own true nature, and discern the way it imagines and represents the divine nature with its loving embrace for all creation. Thus, many writers, though they discussed the discipline which was needed, also wrote on the kind of person that discipline should produce, which is what St. John Moschos did when he gave an account of a monastic elder who constantly looked for ways to help others:

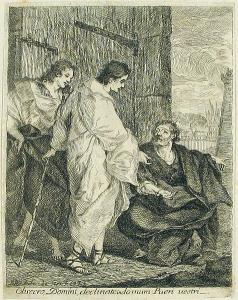

There was an elder living at the Cells of Choziba and the elders there told us that when he was in his <home> village, this is what he used to do. If ever he saw somebody in the village so poor that he could not sow his own field, then, unknown to the man who worked that land, he would come by night with his own oxen and seed – and sow his neighbour’s field. When he went into the wilderness and settled at the Cells of Choziba this elder was equally considerate <of his neighbours>. He would travel the road from the holy Jordan to the Holy City <Jerusalem> carrying bread and water. And if he saw a person overcome with fatigue, he would shoulder that person’s pack and carry it all the way to the holy Mount of Olives. He would do the same on the return journey if he found others, carrying their packs as far as Jericho. You would see this elder, sometimes sweating under a great load, sometimes carrying a youngster on his shoulders. There was even an occasion when he carried two of them at the same time. Sometimes he would sit down and repair the footwear of men and women if this was needed, for he carried with him what was needed for that task. To some he gave a drink of the water he carried with him and to others he offered bread. If he found anyone naked, he gave him the very garment he wore. You saw him working all day long. If ever he found a corpse on the road, he said the appointed prayers and gave it burial. [3]

It is easy for a monastery to become like Sodom and Gomorrah if its monks misunderstands the point of asceticism. That is, it can find itself embracing the vices of Sodom and Gomorrah if its monks engage rigorous asceticism as a way to entirely reject the world and those living within it. For, denouncing the world as evil, they quickly swell up with pride, thinking they deserve every benefit they get, trying to keep it to themselves without sharing it with outsiders, and as such, they truly display the qualities condemned by Ezekiel: “Behold, this was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had pride, surfeit of food, and prosperous ease, but did not aid the poor and needy. They were haughty, and did abominable things before me; therefore I removed them, when I saw it” (Ezek. 16:49-50 RSV).

The comfort of the monastic community, the spiritual pride which can follow rigorous discipline, and the security of the monastery, allowing those within the be filled with food and drink, can easily make monks forget themselves and what they should become. Despite the appearance of holiness, they can end up being far from it because they have ignored the point of it all, which is to become more like Christ. But, as we see in accounts such as the one given above, many in the monastic communities knew and understood this, and so they served, by their examples, as teachers of their community, reminding them what they should be like. They showed that, no matter what they were doing for their own personal holiness, they should not neglect their responsibility to others. We can also learn from these, accounts, because, we too, need to remember that the best life is a life lived in charity.

We are to love and be loved. This should be at the forefront of our teaching, whether we teach by words or by deed. And as love, for it to be true, requires more than words, but actual deeds, if we are to teach only by words or deeds, it is far better to teach by deeds. For then, those who listen to us, those who follow after us, will know we truly value the path of love, instead of merely speaking about it while hypocritically acting against it. And seeing how much we value such love, they will feel the call to follow the path of love themselves, and through it, develop themselves the best they can and see, in that love, the way everything is made better, including their own lives.

[1] Venerable Bede, “Commentary on James” in Commentary on the Seven Catholic Epistles. Trans. Dom. David Hurst, OSB (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1985), 65.

[2] Origen, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans: Books 6-10. Trans. Thomas P. Scheck (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2002), 214-5.

[3] St. John Moschos, The Spiritual Meadow. Trans. Jon Wortley (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 1992; repr. 2008), 16 [#24].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!