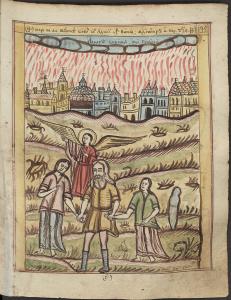

Sodom and Gomorrah are frequently brought up in Christian conversations, but often for the wrong reasons. Too many think of them only in relation to sex, and not to the fundamental errors Scripture indicates lay behind the destruction of the cities. Politicians, and demagogues, like to mention them for the sake of culture wars, once again, dealing with sexual matters, while ignoring the real reason why the sins of Sodom and Gomorrah cried up to heaven. Yes, there was sexual immorality, with the worst kind represented in the way many of the people were shown wanting to sexually assault strangers (who happened to be angels) when they visited the city. Their attitude, their desire to dominate, control, and cause harm shows us what the real problem is, the one which the prophet Ezekiel called out and warned Israel not to imitate, the problem of social injustice: “Behold, this was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had pride, surfeit of food, and prosperous ease, but did not aid the poor and needy. They were haughty, and did abominable things before me; therefore I removed them, when I saw it” (Ez. 16:49-50 RSV). The libertine lifestyle many think about when reflecting upon Sodom and Gomorrah certainly was an issue, but it was an issue because it represented the crass selfishness of the people. All they sought after was their own private pleasure, even if it came at the expense of others (which is why so many wanted to rape strangers, because they saw it another opportunity to embrace their wildest passions and experience the pleasures they believe would come from it). Prosperity itself was not the issue, it was how they used their wealth, which is how they used everything: in an exploitive manner, showing no care or concern for the consequences of their actions upon others (save for Lot, and perhaps the rest of family). They built gates around their cities to fortify their wealth, and with it, the lifestyle which flowed their prosperity allowed them to engage – again, only Lot would be different, as he would go outside the city gate awaiting those in need, helping them as he could (which is one of the reasons why he could be saved).

The sin of Sodom and Gomorrah cried out to heaven because the people of Sodom and Gomorrah were a menace to the world. Likely, they were as destructive to the land around them as they were to the strangers who came to be with them, strangers who were asked either to become like them, making Sodom and Gomorrah great, or else to suffer harshly at their hands (and sometimes, probably, both). If we learned the lesson of the story, we would not follow their destructive ways; we would be kind and considerate to others, and work to take care of the planet around us instead of exploit it, because such exploitation ends in destruction. Sadly, it doesn’t seem we have understood the point. Far too many Christians act just like the people of Sodom and Gomorrah: in their prosperity, they exploit all those who come around them, and through their wealth, they think they have a right to treat others, especially foreigners, with contempt; they show no care for the earth, let alone the future of humanity, all the while saying their prosperity makes them great.

The “Song of Moses” in Deuteronomy is one of the places where we find Sodom and Gomorrah mentioned, and it does so, not just to talk about how bad Sodom and Gomorrah were, but to show how the spirit of Sodom and Gomorrah continues after the cities were destroyed. It talks about how many, who otherwise claim to follow God, take more from the “vine” of Sodom than from God: “For their vine comes from the vine of Sodom, and from the fields of Gomorrah; their grapes are grapes of poison, their clusters are bitter” (Deut. 32:32 RSV).

St. Maximos the Confessor, when asked how we should interpret the verse, followed the tradition of his time which said we should find out how to make the text relevant to the contemporary reader instead of just talking about its historical meaning. To do that, one engages allegory, analogy, and anagogy, which, for Maximos, meant translating the meaning of the names of Sodom and Gomorrah, explaining what those names mean for us:

“The vine of Sodom” is irrationality. “Sodom” is translated as looking into, or, rather, blindness, and Gomorrah is translated as “embitterment.” For the embitterment of sin results from irrationality, and the manic drunkenness of evil is from wine. From that point, the passage commands the Nazarite to abstain from such wine; and “Nazarite” is translated as “one who is fenced about.” For it is necessary for the one who has become secure in the law of God to abstain from this wine of irrationality, but also from the grape, that is, from anger, and from the raisin of resentment, for this is the aging of anger; but also form vinegar, from the sadness resulting from the failure to achieve things according to taking vengeance against one’s neighbor – for all fortified drinks are sweet; but also from the pressed remains, the intentional and concentrated (sustatika) forms of evil. But such a person does not cut off his hair, that is, the various concentrated thoughts of the nous that lends amendment to it. [1]

Maximos, therefore, tells us that we are to engage the world around us, not blindly, that is, not being directed by our inordinate passions and desires, giving into them, no matter what they suggest we should do, but according to the use of reason, directing and moderating our passions. The people of Sodom were blinded by their desires, and so through that blindness, they lost the sense of justice; without such justice, they then did whatever came to mind, whatever their passions suggested, without considering whether or not they should do so. Similarly, he said that Gomorrah represents “embitterment” and so anger and bloodlust, the kind of passion which develops when people think they should get whatever they want, do whatever they want, and are justly prevented from doing so. Those who are rich and wealthy, those who are prosperous, often think they should be given room to do whatever they want, that the law should not apply to them, and we can see how they rage whenever someone tries to stop them.

We do ourselves a great disservice if we read the story of Sodom and Gomorrah merely as a story about sexuality; rather it is a story about the lack of restraints, the kind of restraints which comes about when we use our reason to embrace the way of justice, mercy and compassion. It is the kind of story which, if considered in this fashion, criticizes many of those who claim to be religious but who ignore the plight of their neighbor, the plight of the poor and the oppressed, promoting instead, the desires of the rich, because they want to join in with the rich, having their every fantasy fulfilled. It tells them that such a way of life leads not only to their own destruction, but to the destruction of the society around them.

Sodom and Gomorrah, therefore, should be seen to represent the kinds of societies where basic compassion, basic justice, and the common good is rejected. It should not be seen merely as a story about sexual passions, thinking the main issue God had with the people was that they gave in to their sexual desires. While, to be sure, they did give in to their lusts, they gave in to so much more, so much worse. The cities thought they were great, and thought that to be great, they would need to continue to be free to do as they wish, no matter how much their actions hurt others. The story we have concerning them is a warning of what happens when we lose sight of the common good, of the good will and hospitality which we should have for others; eventually, when the common good is destroyed, society will eat itself us and destroy itself, leaving nothing behind, which is exactly what we see happened with Sodom and Gomorrah.

[1] St. Maximus the Confessor, Questions and Doubts. Trans. Despina D. Prassas (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2010), 70.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.