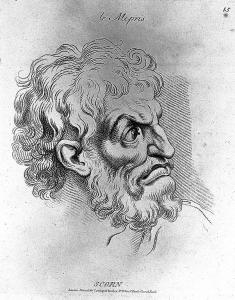

Charity, love, is at the heart of authentic Christian morality. What we do must be borne out of love. When we try to engage morality through any other means, such as legalism, we ignore love, and as such, our moral claims have no proper foundation on which to stand. There are many ways we can and should engage love, yes, and so different people, different saints, will express its meaning within their own context. This shows us that our particular engagement with love must be done in and with wisdom. We should understand what is good in one situation might not be as good in another. This is how and why legalism falters, as it knows none of the balance and nuance which wisdom embraces. Abba Theodore of Pherme, therefore, can be understood as doing this when he said, “There is no other virtue than that of not being scornful.”[1]Scorn has us act contrary to what love would have us do, as it has us despise someone for those qualities we find scornful. And as Abba Theodore was speaking especially to monks, who were actively seeking to root out all the inordinate passions which would have them act contrary to the perfection they were seeking in their lives, it is clear he was telling monks this because they often think of their disciplines as being what makes them virtuous, and as such, they use their disciplines to judge others, especially those who are not monks, scorning those who are not as disciplined and focused as they have become. He was pointing out, therefore, if they follow that route, they will have rejected the root of virtue, and so will never have the perfection they seek. And if there were any doubt, he made it clear, someone should not become a monk because they despise others: “The man who has learnt the sweetness of the cell flees from his neighbour but not as though he despised him.” [2]

It is a common for people to assume monks (and nuns, though in the early Christian era, all nuns were also referred to as monks) flee the world, in part, because of hate for the world and those who live within it. It is quite possible some did do so for this very reason. But this stands against the monastic principle. Monks might flee the world, but it is not out of hate for the other, but rather, as a way to get to a place they can engage an intensive ascetic regime, to make sure they remove themselves from temptations and situations which would otherwise hinder their own spiritual and moral development. The development, moreover, is not just for themselves, but for others, as they believed the better they become, the more they can and will help the community and the world around them. Thus, while some have been led to see an individualistic moral principle underlying monasticism, in reality, monks were not so cut off from the world and their responsibility to it; they engaged their discipline, not just for themselves, but for the good of all. Those who became monks without a sense of love, without a sense of compassion and care for the community at large, cut themselves from the foundation they need to make sure their discipline was effective. And so, as Abba Theodore of Pherme indicated, their scorn of others would make sure they would not develop the virtue, the holiness, that they desired for themselves. So long as they could not love their neighbor, everything else they did, however great it was, would not help them, but instead, could actually stand in the way of attaining true virtue.

This is not to say Theodore thought monks should ignore the things which could help or hinder them in their own spiritual development. He knew we can all be and are influenced by those around us. This, again, is one of the reasons why someone can seek to be a monk, to get away from the world, as it were, because they want to cut themselves off from bad influences. But even then, care must be had; Theodore thought the worst influences come from those who would otherwise influence us with heretical notions, encouraging a disoriented, lopsided spirituality, and not those whose lives could be said to live a sinful life, for the problem with bad ideologies is how easy they can corrupt us, even if we try to fight against them and resist them (perhaps, this is one of the problems many professional apologists face). Thus, while not being scornful to anyone, he said:

If you are friendly with someone who happens to fall into the temptation of fornication, offer him your hand, if you can, and deliver him from it. But if he falls into heresy and you cannot persuade him to turn from it, separate yourself quickly from him, in case, if you delay, you may be dragged down with him into the pit. [3]

We must understand the context of his words lies in the way particular monastic communities often found themselves coming together in order to put into practice various ideological notions which they had come to believe. Theodore, in his wisdom, was warning would-be monks to be careful when determining which monastic communities to engage or embrace. For if a monk would join a community based upon poor theological and spiritual principles, they would find that the community will hinder, instead of help, their spiritual development, as would happen, for example, if they joined a community tainted by Gnostic ideologies which denied the good of the body and the material world. We, on the other hand, can understand the wisdom behind his words in the way we choose the relationships we keep, such as on social media, and how we sometimes have to cut ourselves off from others because of how aggressive they come at us with their ideological slant, wanting to take up all our time and thought, disturbing, therefore our own spiritual pursuits. When we find our lives dominated by those trying to cause trouble, those only wanting to challenge us, to criticize us without mercy or love, we will end up being dragged down by them. If we do not become convinced by them, we will slowly experience a banter riddled with scorn, and as such, we will find ourselves being led astray, not because we accept their ideology, but because we find ourselves losing the love and compassion we know we should possess. But, what is more, what Theodore said about sin is very important as well – we must realize that our embrace of others when it is done in and with love, will not lead us astray. What will is holding others to scorn, for that scorn will eat away out us, and our own goodness, while doing nothing to help those we criticize. We must love others. Our interest in them must be to love them, and so our task first and foremost, is to see them as people to be loved, not as sinners who need our correction. We should love them for who they are, not what we want to make out of them. The more we do this, the more we will find everyone, including ourselves, will be made better through that love, revealing that we have truly taken in and accepted the teaching of Christ, which is the teaching of love itself.

[1] The Sayings of the Desert Fathers. trans. Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1984), 75 [Saying of Abba Theodore of Pherme #13].

[2] The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, 76 [Saying of Abba Theodore of Pherme #14].

[3] The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, 74 [Saying of Abba Theodore of Pherme #4].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!