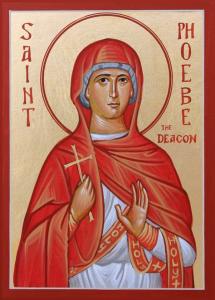

Church history shows that there were many women who were ordained as deacons, many of whom were also saints. Indeed, the Council of Chalcedon, in stating when they could be ordained, shows us women were ordained as deacons (i.e., deaconesses):

A woman shall not receive the laying on of hands as a deaconess under forty years of age, and then only after searching examination. And if, after she has had hands laid on her and has continued for a time to minister, she shall despise the grace of God and give herself in marriage, she shall be anathematized and the man united to her.[1]

Some try to deny that Chalcedon indicates women can be ordained deacons by suggesting the word, normally used to indicate ordination, meant something else when talking about women. This is because they say the word can mean different things, just as the word for deacon can mean many things. In doing so, they do not see how they have created an argument, not just against the ordination of women into the diaconate, but against all forms of ordination in the ancient world. For it provides the means by which we can deny anyone was ever ordained, that when the word is used also for men, such as men being ordained as deacons or as priests, the word also didn’t really imply ordination in the way we take the word ordination to mean today. They, of course, try to argue that the word implies ordination when it applies to men, but in doing so, they demonstrate the kind of sophistry which should make everyone question their reliability, as they are inconsistent in how they engage texts which talk about ordination. In reality, we can see this is just a defensive posture, where they are trying to deny the historical record and what it actually presents so as to support a predetermined conclusion. They do not want to accept the possibility that women can be ordained and considered among the clergy (as deacons), even if ancient texts, such as the Code of Justinian, showed women deacons were considered among the ordained clergy and not just the laity.

Thus, many have come to a particular conclusion, and force that conclusion out of the texts they use. That is, they engage proof-texting, with all the problems involved with that kind of methodology, such as taking particular quotes out of context to imply a meaning not given in the greater context. We can see this in the way some engage Canon XIX from the Council of Nicea:

Concerning the Paulianists who have flown for refuge to the Catholic Church, it has been decreed that they must by all means be rebaptized; and if any of them who in past time have been numbered among their clergy should be found blameless and without reproach, let them be rebaptized and ordained by the Bishop of the Catholic Church; but if the examination should discover them to be unfit, they ought to be deposed. Likewise in the case of their deaconesses, and generally in the case of those who have been enrolled among their clergy, let the same form be observed. And we mean by deaconesses such as have assumed the habit, but who, since they have no imposition of hands, are to be numbered only among the laity.[2]

Usually, they will quote a small portion of the canon, the part which discusses Paulianist deaconesses, and say this proves that Nicea denied women could be ordained to the diaconate. “And we mean by deaconesses such as have assumed the habit, but who, since they have no imposition of hands, are to be numbered only among the laity.” What they do is ignore the context in which this text is to be found. It is a discussion of the Paulianists, and how the church is treat those who once were among them but have come back to the Catholic faith. The Paulianists denied the proper teaching of the Trinity, and embraced modalism, which is why the text said that their baptism was to be rejected. As their baptism was invalid, so their ordination was also invalid. Those who were chosen among them to be clergy could be recognized as clergy once they became a part of the institutional Catholic church, but to do so, they would have to be baptized and then ordained. Those women who were among them, who took on a position of helper, named among them as deaconesses, were not considered by them to be among the clergy, and so were not considered ordained by the Paulianists. This is why, when they came into the institutional church, they also were recognized as coming from the laity, and so were not ordained deaconesses. Now, if one were to accept the argument, since their women were not ordained as deaconesses, no women could be ordained as a deaconess, thanks to the words in the canon, the rest of the canon would have to be read similarly, giving universal declarations. Thus, as none of their men were properly ordained, would we not have to conclude no one can be ordained? The canon itself shows this is not the case as their clergy could be accepted into the church and ordained, showing that ordination is possible. Thus, if the rhetoric used about Paulianist clergy does not lead to a universal statement indicating that there is no such thing as ordination, then its discussion concerning Paulianist women called deaconesses, who were not recognized by them as being among the ordained clergy, does not give a universal statement about women and the possibility of their ordination to the diaconate. The fact is, those who try to deny women deacons based upon this passage, do not deny the possibility of ordained clergy, and so they understand that the canon is to be read contextually; it seems the reason why they do not exercise caution when dealing with its statement about women deacons, seeing it relates only to the sect in question, lies in the way they use an ideology (if not outright misogyny) as the basis of their hermeneutic.

In reality, far from suggesting women can never be ordained as deacons, the canon actually implies the reverse. If what the council wanted us to believe is that women couldn’t be ordained as deacons, they would have said Paulianist deaconesses are not ordained deacons because women cannot be ordained. What they said is that they are not ordained deaconesses because they did not undergo such ordination within their sect. The difference is key. It implies that there are other women who have undergone ordination, the laying on of hands, and so are ordained deacons. It gave a condition by which it denied Paulianist deaconesses from being ranked among the clergy. What is necessary is the intention of ordination and the actual act of ordination, neither of which was found with the Paulianists, and so their women, chosen to serve a particular role in their sect, were not seen as holding equal status to women in the institutional church who had received such ordination. It would be no different than saying someone cannot drive a car because they do not have a driver’s license; saying that does not mean no one can drive cars, nor that no one has a driver’s license, but rather, it suggests that there are people who can drive a car, because there are some who have the license which is needed. By saying the Paulianists women who were called deaconesses were not ordained and so to be considered among the laity, implies that other women have been ordained and are reckoned to be among the clergy. Thus, the canon actually suggests that there are women who have been ordained with a laying on of hands, and because they have been, they are recognized as ordained deaconesses, but women coming from sects who did not even consider doing so, are not to be brought into the church as the equivalent of those women who were ordained.

Far from making a universal statement denying the possibility of deaconesses, Canon XIX from Nicea dealt with the status of the so-called deaconesses coming from the Paulianists. The argument used in it has universal value. We must keep track of the argument and not just the particular conclusion in regards the Paulinists. That argument suggests that to be classified among the clergy, and not just the laity, women deacons would have to be ordained. It didn’t say they couldn’t be. It didn’t say there were no such women deaconesses. Indeed, by saying ordination is requirement , without making that denial indicating that the requirement is impossible, tells us that they think women can be ordained as deacons. Reading the text, within the context it was written, looking both to the argument employed and why that argument led to its particular conclusion only provides further, not less evidence, that women can indeed be ordained as deaconesses. And, we know, though there were communities where women were not treated as ordained clergy, there were others in which they were, which is why Nicea declared what it did, allowing those communities who did not have ordained women deacons to remain as such, while recognizing others who did ordain them, were not to be denied.

[1] Canon XV from the Council of Chalcedon in NPNF2(14):279.

[2] Canon XIX from the Council of Nicea in NPNF2(14):40.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!