The Great Fast reminds us of ways we can and should get to know ourselves better. That means, of course, it is about metanoia, about repentance, even as it is also about forgiveness. We need to accept forgiveness for ourselves. While recognizing our own faults, we should not be too harsh or critical of ourselves, for such harshness leads to despair. We must come to terms with who we are. We must recognize the good as well as the bad, seeing the good as why we should accept forgiveness and all the graces which come with it. But we must also come to terms with the ways which we have failed ourselves. We should discern the reasons why we have had such failures. Recognizing the good will help us accept forgiveness despite all those failures, for we will see that they do not take away from who we are. We can truly become free, free from all the failures, and all the ways those failures have come upon us, either by ourselves, or by the hands of others. We are not in this alone. Much of what we do, good and bad, comes in part from our relationships with others. When people treat us badly, and only expect us to act poorly in return, we end up giving them what they expect – we let them, in this way, gain some control over us, and so through their bad influence, we often find drifting away from who we really are.

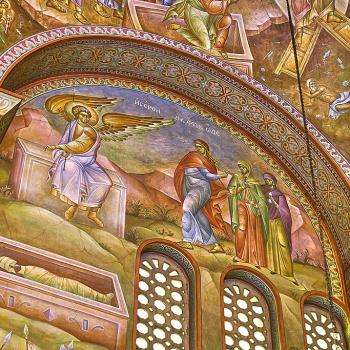

We see this presented in the story of St. Mary of Egypt, and in the way she is remembered on the fourth Sunday of the Great Fast in the Byzantine tradition.The legends we have of her often highlight the way she turned her away from a life of prostitution to that of a holy ascetic, eventually becoming a solitary living out in the desert all by herself. She is said to have lived many years all by herself until, near the end of her life, she had a brief encounter with a priest, an encounter which allowed her to tell her story to him, whereupon she asked him to bring her communion, which he did soon before she died. There are many ways to read and interpret these legends, some, which are popular, are rather offsetting, as they suggest Mary was totally at fault for her life of prostitution, making her story not one which highlights her nobility and greatness, but one which diminishes her; they are misogynistic readings which, like so many misogynistic reading of “sinner”-saints, uses her as a scapegoat for the sins of others. If we examined her life more carefully, we should note society, and not Mary, was at fault for what happened, as it did nothing to help or protect her when she needed it. She had nothing. She couldn’t survive on her own. Society failed her. She did what she needed to live. Men used her and abused her. It was society, it was men, who were at fault. If she had been treated justly, if men didn’t just look at her as a thing to be used but instead someone to help flourish in life, she could have kept her innocence and found her way much sooner. But she was always innocent. She was always one whom Jesus loved. This is why Jesus, through the help of the Theotokos, directed her to turn her back on society, away from the prying eyes and abusive hands of men in order to find her dignity, and with it, much joy and gladness. It was men who made her into something she was not to be, and it was getting away from them, she was then set free and truly found herself. This is something we find hinted at in the normative version of the story which was made concerning her life, though the earlier rendition of her life made by Cyril of Scythopolis in his The Lives of the Monks of Palestine, implies something similar; in it we are told a somewhat different reason for why she went out to live alone in the desert, even as we are given a different telling as to how her existence in the desert was discovered:

My name is Mary. I became cantor of the holy church of the Resurrection of Christ, and the devil made many scandalized with me. Fearing lest, in addition to being responsible for such scandals, I should add sin to sin, I entreated God to rescue me from being the cause of such scandals. [1]

Once again, we can discern a misogynistic reading of her life, suggesting that she was to blame for what others thought. It is possible this led people to wishing she had been a prostitute, and slowly making her backstory so that she became what they desired her to be. It is also possible the stories can represent elements of a story which none fully tell; she might have been a prostitute who, after her conversion, become a cantor, but people looked upon her based upon what she had done to survive. If we can say that someone who steals in order to survive finds their need renders their culpability to being slim to none, we can suggest similar mitigating circumstances affect the culpability of those who find themselves forced into a life of prostitution. The key, once again, is to understand how society helps create the situation by not helping those in need. And, of course, men in society have all kinds of reasons to want to keep it that way. Thus, whether she was a prostitute, or she was just someone men fantasized over, it is important for us to place the majority of the blame on the men. She shouldn’t be blamed for what others thought of her. She had become a cantor, and it would seem, men found themselves attracted to her. They took advantage of the situation, and so she found herself manipulated and abused by them, all the while they tried to tell her it was her fault, a common excuse given by men to those whom they abuse. Sin was added to sin, as the “devil,” the evil in men’s hearts, led them to engage thoughts and activities which would bring scandal to the church. The only solution she could find was to get away from it all, to live alone, outside of society, outside of the evil which lies in the hearts of men; she was not the cause of the scandal, but she was made to feel such by men, and so by getting away from them, she was able to free herself from their abuse. Once free, she was able to get to know herself and her great dignity, the dignity which men wouldn’t let her find so long as they had power over her. Because of what they had done to her, she had to make a break from society and live a solitary life in the desert. There, without all of the abuse, without all the manipulation, without all the scapegoating which made her feel as if she were to blame for all that was done to her, she found the grace and way of life she needed for her own good, a life far from all the men who would abuse her if they could.

What we should learn from this is that when society turns people into outcasts, forcing them to live and act in ways which no one likes, society should be seen as the one to blame, to be the one culpable for what those people do. Sadly, its victims tend to be turned into scapegoats, and as a result, the ones society have abuse get more and more abused aimed at them. Such people need to find a way to get beyond society, from the pressures society put on them, and especially, from the systematic structures of sin which reinforces the evil done by society, so that they can move beyond the abuse and the scapegoating which constricts and wounds them. Once they do so, they can truly come to know themselves, seeing the good within which society did not want them to see. That is, they will come to know the good within themselves, the good which God sees and loves. Seeing it, they will accept God’s grace and help. They will acknowledge they might have done some wrong, thanks to the pressures put on them, but they will be able to see why such wrongdoing does not define them. Thus, they will find themselves capable of transcending their past as they truly come to realize their own potential and greatness.

St. Mary was a beautiful young woman that was used by all kinds of men who had no care or concern for her; indeed, once they had their way, they treated her with contempt, making her feel everything was her fault, when she was the one who had the least bit of agency in the situation. She found her agency once she was able to get away from all the evil influences coming upon her from society, that is, from the men who wanted to use and abuse her. She was set free, and the pure, lovely young woman was able to come to her self, to know what men and society did not want her to know.

We, too, must realize that we have to get beyond the influence of society, at least in regard the systematic structures of sin which society embraces, to push beyond them, so that we can engage the path which leads us to knowing ourselves. Thus, the Great Fast reminds us not only of the things which we have done with our own free agency, things which we should truly repent for doing, but also of the things which we have done while not being so free, allowing us to understand that when there is no such freedom, we have little to no culpability for what we do. We are not always the free agents we are led to believe, and so we are not always as culpable for all we do. Systematic structures of sin infect society, and those who embrace those structures and use them for power and glory, are truly those who are most culpable, even if they will try to find a way to dismiss their own culpability by placing the blame on those they have manipulated and abused. We, therefore, must work to overcome those systematic structures of evil. Sometimes, that might mean we need to get away from it all in order to come to know ourselves and see the good which they tried to circumvent. But often, it means, we must stay where we are and fight those structures, seeking to eliminate them from society, transforming it from within. Then, we shall find we are helping not only ourselves, but society as a whole. And in the end, as the story of St. Mary shows us, it is those who have been pushed down, those who are humble, even if they have become compliant to their abusers, who are the ones who will be lifted up and shown for how glorious they really are. For, as we have been told, the first shall be last, and many of those whom the world thought nothing of will be the greatest in the kingdom of God.

[1] Cyril of Scythopolis, The Lives of the Monks of Palestine. Trans. R.M. Price (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 1991), 257 [Life of Cyriacus; Mary of Egypt?.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.