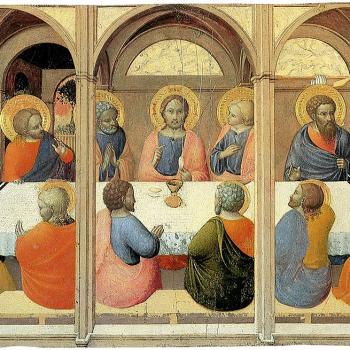

While we can, and will, contemplate and try to understand the eucharist, we must keep in mind it is one of the great mysteries of the faith. Our reflections must not lead us to take away from its transcendent character. While many, if not most Christians, have a faith seeking understanding, we must not confuse our understanding and the rationale we give for our it with the fullness of the faith itself. We must not even confuse the explanation we give with the teaching it is we are trying to explain. If we do that, we would end up undermining the faith by limiting it to our own comprehension instead of allowing it to direct and guide us beyond what we know and understand. If we already know and comprehend all truth, we will have nothing more to learn, nothing more to discern, no mystery to inspire us. Everything will become ordinary and routine, indeed, boring.

When we think of the faith and its teachings as simple propositions which we not only can know, but fully comprehend, we invert our relationship with the faith and its teachings. We end up thinking we are the ones who determine the truth, making us dismiss what we do not know or comprehend as false.

When learning about the eucharist, we must not confuse the various explanations given to explain it, including how bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ, with what it is which must be believed. They are, of course, going to be related, as the explanation will try to keep in mind and present the truth, but because there can be and are other ways of explaining and presenting the truth, disagreement with one explanation for it does not mean disagreement with the truth itself. What reason offers are conventional explanations which help us understand the truth the best we can, but they rely upon our understanding, that is, what it is we are able to comprehend. Different people will have different levels of comprehension, and so different kinds of explanations. Sometimes, various explanations are incompatible with each other, but not the truth being explained, so that they are all acceptable, while other times, someone can make a bad explanation which will lead to mistaken views, mistaken concepts, which counter what the faith teaches, and when they do so, they need to be corrected and their explanation rejected. What is important is the teaching, not the explanation, which is why Lanfranc of Canterbury, whose writings on the eucharist were important in defending the real presence when it was being questioned in the 11th century, made it clear, we should not overly analyze the eucharist and how God makes it available to us:

How the bread is converted into flesh, and the wine is converted into blood, and how the nature of each has essentially changed, the just man who lives by faith does not seek to scrutinize by argumentation and grasp of reason. [1]

This is why the explanation being offered by the notion of transubstantiation must not be confused with the doctrine of the real presence; people can and do believe in the real presence without accepting all the intricacies associated with transubstantiation. Transubstantiation is an explanation for how we receive that presence, an explanation which requires acceptance of many premises, premises which we do not have to accept to believe in the truth of the eucharistic doctrine. What we are promised is Christ, and what we receive is Christ. If we believe this, if we believe what we receive, though it appears to be bread and wine, is truly Christ and not what it appears to be, that is sufficient. Of course, we can try to discern how this is so, but when we do that, we must be careful, as we can then begin to assume our explanations have more value than they are, and think they are necessary conclusions based upon the doctrine of the eucharist instead of attempts to present the doctrine. Perhaps this is the problem which emerged with the notion of consubstantiation: it was developed as a way to preserve the truth of the real presence, but it did so with bad premises, causing truth to be mixed with error. When particular explanations, and the technical vocabulary connected with them, are over-emphasized, the technical meanings of the vocabulary get lost over time, leading to those who do not understand them to misconstrue the explanation and come to an erroneous belief. Is this not what happens when people here the word substance today? They think of it in a physical fashion, leading them to an overly-physical understanding of communion, where they think the eucharist is mere flesh and blood.

The mystery of the incarnation relates to the mystery of the eucharist. When we are offering explanations for the eucharist, just as when we are trying to offer explanations for the incarnation, we are trying to discern supra-temporal realities in a temporal, indeed, materialistic fashion. What we know and understand the most is the physical world and qualities associated with it, like time and space. Supra-temporal existence is, for us, an abstraction. The eucharist, as it is Christ, is a reality which transcends our experience. We will tend to engage it with spatial and temporal qualities, just as we will engage Christ with those same qualities. This is why, even if we know and understand that there is but one eucharistic sacrifice shared throughout all time and space, we tend to view each and every reception of communion as a different event, as it is a different event in our own personal history:

How can one express in the language of time these supratemporal events, which, although they bear the stamp of temporality (for they were confined to the boundaries of space and time), at the same time abide beyond it? They are eternal in the Divine power, but are welded together in time, and are revealed in and through it. This dual, antinomical character was inherent in the Incarnation and its dual-naturedness, in which the True God united Himself with human nature, and became the True Man. Divinity reveals itself to humanity, and the latter receives in itself the revelation of the Divine. This is the whole mystery of the Incarnation, and it also includes the Divine Eucharist. Though it occurred on one day, at a specific place and time, it also takes place supratemporally in heaven in just the same way that it is “repeated” on earth as “remembrance.” By the power of God, in this frequent repetition, they are fused together into a unity reaching all the way to the total identification that is sacramentality. [2]

Once again, if we are not careful, our materialistic existence, our general lack of spiritual experience, will transform our understanding of the eucharist so that we view it as being physical, and as such, bound by time and space. Then, we will begin to confuse what we receive as being different each time, so that instead of viewing it as one sacrifice across time and space, we will think we are participating in and experiencing many different sacrifices, each one repeating what had gone on before it.

It is important, therefore, whenever the eucharist is discussed, whenever we try to explain what it is we receive and how we receive it, we do not confuse our explanations for the teaching as being the teaching itself (even as we should not confuse our interpretation of Scripture as necessarily being the real meaning and intention behind a Scriptural passage). They are related, to be sure, but they are related in the way a pointer is related to the object being pointed to. If we become too focused on the explanation, trying to preserve and protect it, to defend it and extrapolate more and more theological notions based upon it, we will begin to wander and stray, until at last, we will find ourselves going the wrong direction and undermining the truth which the explanation was meant to preserve.

[1] Lanfranc of Canterbury, “On the Body and Blood of the Lord” in Lanfranc of Canterbury: On the Body and Blood of the Lord and Guitmund of Aversa: On The Truth of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist. Trans. Mark G. Vaillancourt (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2009), 61.

[2] Sergius Bulgakov, The Eucharistic Sacrifice. Trans. Mark Roosien (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2021), 13.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.