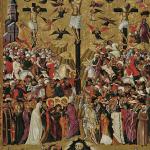

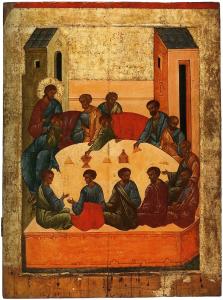

On the night on which Jesus was betrayed, a betrayal which he expected and was ready for, Jesus first handed himself over to his disciples at the Last Supper, giving himself completely to them in the institution of the eucharist. Then, later, when the soldiers came to arrest him, he did not resist arrest. In all that he did that night, Jesus revealed to us some aspect of God’s love for humanity. Jesus let himself be taken, judged, condemned, and sentenced to death, so that he could reveal that nothing would ever overcome God’s love for humanity, even if and when humanity came together to kill him. With the eucharist, he provided a means, a sacramental means, by which people who loved him could and would welcome him into their being, and through that means, find themselves uniting with him in a communion of love.

The reality of the eucharist is that it is Christ; it is not just a part of Christ, but all of him and who he is as a person. While the eucharist is truly Christ, the presence of Christ is said to be a sacramental presence and not a physical presence because what is physically present, what people experience in and through their senses, are bread and wine. Substantially, essentially, bread and wine brought to the table are transformed and become Christ, which is why its reality is no longer that of bread and wine, and yet the physical qualities of bread and wine remain, and it is these qualities which are apprehended by the world. Physically, then, we have before us bread and wine, with the bread symbolically representing the flesh of Christ, and the wine, that of his blood. The reality which is received when either the bread or the wine are received is not bread or wine, nor a part of Christ (like his flesh or blood), but all of who and what he is. Thus, we should understand that our reception of the sacrament involves a symbolic representation of the reality which we partake, a symbol which will not be necessary in the eschaton:

The body of Christ is received presently under an appearance, that is, sacramentally, in order to signify that union by which we will be conformed to God. This will happen when we will see Him as He is. Nevertheless, those who receive [the Eucharist] worthily do not receive less than the reality itself. And it is not surprising that this receiving [of the body of Christ] is a sign of some union, considering that all things whatsoever that are in the Church on earth are signs of future realities. For in the future there will be no things that are signs of other things. And this is what it means to receive by the truth of the reality, that is, not figuratively. [1]

If what we received was some mere physical presence, the rules of physics would apply, which means, we would be receiving a part of Christ, not the fullness of Christ, when we partake of communion because we do not partake of all the communion which is available in the world but only a part of it. But what we receive is not bound by physical laws. The eucharist is the fullness of Christ, no matter how much or how little we partake. “In the flesh and blood, both which are invisible, intelligible, spiritual, there is signified the body of the Redeemer, which is visible, palpable, manifestly full of every grace and virtue and divine majesty.” [2] And, as St. Albert the Great explained, the celebration of the eucharistic rites does not change Christ: it neither adds or subtracts anything from him:

For so in the sacrament, he used a new mode of making by which the bread is sacramentally made into the body of the Lord, so that the substance of bread is neither annihilated nor altered nor changed in accordance with the substance, but without any addition or change the whole substance of bread in the matter and form of bread is converted into the body of Christ, and without anything changed in him. [3]

Or, as Guitmund wrote, “… when, however, we say that the bread is changed, it is not changed into that which had not been flesh, but we confess that it is changed into the flesh which was already the flesh of Christ, without any increase in the flesh of the Lord himself.” [4] Guitmund understood the difference between the real presence in the eucharist and the physical presence many think the real presence assumes. He indicated that, when we consider things physically, what we receive continues to be that of bread and wine, meaning, as our physical (sensual) experience is the same which we have when we eat bread and drink wine. But he also understood that what happened to the physical elements, such as if they were burned in a fire, did not touch Christ, once again showing the difference between a mere physical presence and the real presence in the eucharist, for if the presence were physical, then Christ would be harmed by those flames:

If the sacred mysteries are therefore placed in the flames, they are certainly not handed over to the fire to be burned, but rather, are faithfully committed to the most pure element to be hidden from us, as I said, and reposited in heaven. But if perchance to some attentive person they seem to be burned, certainly he will know that the substance of the Lord’s sacrament is never burned; but as we have already said, it is taken away from us and seeks a heavenly place; the sensory qualities, however, which God wills in his most sublime counsel to remain after the change in substance, manifest their own properties. Whence it happens that color, taste, and odor, and any other accidents of this sort of the prior essence, that is, of the bread, have been preserved, and what occurs is the same as what normally happens to the bread that has been burned or kept too long. [5]

This is why no abuse of the eucharist will ever harm Christ, though of course, it can and will harm us if we intend such abuse, as we will be sinning and will have to face the consequences of such a sin.

If Christ’s eucharistic presence were a physical presence, then physical laws would apply to that presence. They don’t. The eucharist completely transcends them, showing us why we must accept the real presence as being something else entirely. Thus, what was given to the disciples as the Last Supper, and what is given to us to this day, is truly Christ, but, as Sergius Bulgakov said, it is Christ coming to us in a way different from his physical presence as his disciples experienced it in his temporal ministry:

Thus the repetition of the Last Supper in anamnesis does not simply concern some earthly body and blood, just as Christ Himself after the Ascension is not present on earth in the same way that He was at the institution of the Eucharist. Hence, we are talking about the Body and Blood of Christ in a different sense, that is, in a Heavenly one. [6]

We truly receive Christ, but we must not think we receive him in some sort of overly physical fashion. “For we eat and drink the immolated Christ on earth, in such a way that he always exists whole and alive at the right hand of the Father in heaven.” [7] We partake of Christ, we open ourselves to him, so that we can then be united with him, and in that unity, lifted up with him so as to find our place in the eschatological kingdom of God.

[1] Robert of Melun, “Questions on the Divine Page,” in Interpretation of Scripture: Practice. Trans. Franklin T. Harkins. Ed. Frans van Leiere and Franklin T. Harkins (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2015), 302.

[2] Lanfranc of Canterbury, “On the Body and Blood of the Lord” in Lanfranc of Canterbury: On the Body and Blood of the Lord and Guitmund of Aversa: On The Truth of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist. Trans. Mark G. Vaillancourt (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2009), 56.

[3] St. Albert the Great, On the Body of the Lord. Trans. Sr. Albert Marie Surmanski, OP (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2017), 333.

[4] Guitmund of Aversa “On The Truth of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist” in Lanfranc of Canterbury: On the Body and Blood of the Lord and Guitmund of Aversa: On The Truth of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist. Trans. Mark G. Vaillancourt (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2009), 117.

[5] Guitmund of Aversa “On The Truth of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist,” 136.

[6] Sergius Bulgakov, The Eucharistic Sacrifice. Trans. Mark Roosien (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2021), 30.

[7] Lanfranc of Canterbury, “On the Body and Blood of the Lord,” 53.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.