Philosophy traditionally tells us about three great transcendentals, that of the truth, the good, and the beautiful. Each of them are understood as their own distinct category, and yet, they are interdependent with each other, meaning, there is a fundamental unity which connects them together. When you have one of them, you have them all. Each of them can be and should be explored in accordance to its own category of thought, but when this is done, we must not lose sight of the relationship they have with the rest of the transcendentals. If we try to treat any transcendental as absolutely distinct from the rest, we end up creating a distortion of the transcendental itself, one which does not allow the transcendental to be all it can be as it loses those elements which connect it to the rest of the transcendentals.

Focusing on the truth without a concern for the ethical implications and activity associated with the truth ends up being something less than the truth itself. Focusing on beauty, ignoring the way it is meant to reflect the truth and promote that which is good, abuses beauty, using it for something which can be described as truly ugly (such as what happened Nazis created posters promoting hatred for the Jews).

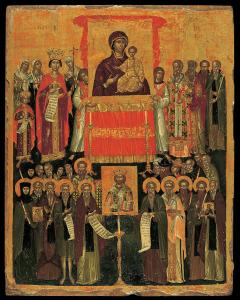

We must consider the qualities of the truth, the good, and beauty, each in their own way, because the distinctions between the three are real, even as we must realize the distinctions do not end up having them become independent from each other. This is why, when we examine one of the categories of thought, and explore it on its own terms, we must also find a way to show how it connects to the other transcendentals, making sure that in this way, we do not end up distorting or abusing any of the transcendentals themselves. This is why, theologically, orthodoxy without orthopraxis end ups undermining both orthodoxy and orthopraxis, or why images can end up becoming idols, while other images, when connected with orthodoxy and orthopraxis, serve a necessary part in the presentation of what is good and true in the world. The Sunday of Orthodoxy, the first Sunday of the Great Fast in the Byzantine tradition, reminds us of this as it is the celebration of the restoration and use of icons, showing us that orthodoxy relates to orthopraxis, and in this instance, a particular kind of orthopraxis, the orthopraxis associated with the creation and veneration of icons.

Orthodoxy without orthopraxis is mere dogmatism, a dogmatism which proves to be empty of any value as the holiness found in and with the truth is denied. Just because someone can recite various dogmatic degrees does not mean they understand them, let allow follow the implications contained in them. Dogmatic decrees, when they are orthodox, point to the truth which lies beyond the words used in such decrees. There is not just one, but many ways this can be done. This is why, when many orthodox dogmatic decrees are put side by side, if they are not properly understood, if people follow them according to the letter instead of the meaning intended by them, they can appear to contradict each other (which is what would happen if one merely reads the original Nicene Creed, which stated there is only one hypostasis for the Trinity, thinking they must follow the letter of the decree instead of its intended meaning; if they do not understand the use of the word hypostasis in the Nicene Creed, they will be confused when other dogmatic decrees talk about three hypostases, but if they understand the way the word hypostasis changed meaning over time, they can begin to see how different ways of presenting the truth of the Trinity actually point to the same truth, and often in ways which complement each other).

Focusing on dogmatic decrees, and therefore the “truth” outside of orthopraxis and aesthetics (beauty), leads people astray; aesthetics helps us understand symbols, and the limitations connected in and with all symbols, but also the value and way symbols, when properly understood, point to the truth beyond themselves. The Sunday of Orthodoxy demonstrates this by affirming the use of icons (beautiful images), explaining that they present to the faithful the truth through the use of images. Icons present the truth in a form of beauty, and through that beauty, show us the way of holiness, encouraging us to join in and experience the holiness and truth presented in them. Beauty attracts, encourages, and motivates us and our hearts, so we not only desire the good and the truth we see depicted, but we end up loving them. But this is why holy images (be it icons or statues, both which are permissible) must properly engage the truth and present to us a sense of the holiness which the truth generates. If the truth is not properly depicted in a particular image, that image is seen as not being a true icon, which is why there are rules and expectations placed in the creation of icons, rules and expectations which can change over time to deal with new cultural situations.

Icons, therefore, give us a way of understanding the truth of the incarnation, one which points out that God, by becoming the man, has assumed all that is contained in humanity, including a body. It is because of that body we now have we can see, and through that sight, have a means to produce an image of the God-man. Since the God-man is God and human, we are depicting, through those images, a person, a person who happens to be God, and in this way, we can now depict God. This was not always possible, which is why, before the incarnation, we are warned against creating images of God, because God, in accordance to the divine nature itself is invisible and incomprehensible, which makes it impossible for us to depict it in an image. That has not changed with the incarnation, because we still cannot depict the divine nature as it is in and of itself, but what has changed is God has provided us an image for us to use in and through the body of Christ, an image which presents to us a divine person, and so God.

The truth of God, the absolute transcendent truth, cannot be comprehended by us, and so cannot be comprehended by images, but, through the way God works and interacts with us, especially in the incarnation, we have a way to apprehend God and through our apprehensions, create means by which we can point to the truth which lies beyond our comprehension. Images, creedal definitions, and the like, when engaged properly, serve as pointers which help us look beyond our current apprehensions, to pursue an even greater apprehension of the truth of God. Through the incarnation, we are shown we can use images, but it is important to realize, that means, we can depict the kingdom of God, and with it, all those who are found in it. Jesus is not alone. Jesus has shared his holiness with others, and we can depict that as well, which is why we can create images not only of Jesus, but of the saints, using them to show us aspects of the kingdom of God. They are the cloud of witnesses who encourage us to seek for and receive the glory of the kingdom of God for ourselves:

Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God (Heb. 12:1-2 RSV).

The author of the book of Hebrews presented to us an image in words, an image which can and is then depicted, not just in words, but with art, with icons. Each icon of a saint represents one of the cloud of witnesses, one of those who clings closely to God, indeed, participates in the divine nature (represented by halos), beckoning us to join them in the kingdom of God. If we are not to use any images at all, then the author of the book of Hebrews would be in error for giving us a mental image; but, again, thanks to Jesus Christ, who is the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, we find God can and will use images to help us to come to know the truth, and through the truth, to find ourselves acting upon the implications of the truth.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.