I became a Byzantine Catholic in my junior year of college. At that time, and for years afterward, two of the most important influences I had for my theological and philosophical development were the works of patristic writers and those philosophers who were, in some way or another, associated with the Platonic tradition (from the ancient Platonists like Plato, Plutarch, Iamblichus and Proclus, to medieval philosophers from the school of Chartres, to modern writers including C.S. Lewis and many of his friends). To be sure, I have not abandoned them, and they continue to be major sources of inspiration for my own personal development, but I engage them in a different, more critical manner, even as I have greatly expanded the kinds of works I read. This meant that those who are both a patristic author and someone who can be seen as influenced by or following Platonism (directly or indirectly), are among those I found to be the most important of all. This is what initially led me to study the person known as Pseudo-Dionysius.

Pseudo-Dionysius wrote as if he were Dionysius the Areopigate, and he took various strands of patristic thought which preceded him, such as from the Cappadocians (Sts. Basil, Gregory of Nyssa, Macrina, and Gregory the Theologian) and adapted them with his own engagement of the Platonic tradition (especially Proclus, who it is clear, he adapted to fit Christian theology). While his Platonic element intrigued me (as can be seen in his exploration of the angelic and ecclesiastical hierarchies), it is his apophatic theology which remains his most significant contribution to Christian thought (and with it, my own theological reflection). He understood Christian theology must always have a caveat in regards what is said, pointing out that all theological reasoning fails to comprehend who and what God is, that God transcends all our comprehension, and so we need to approach God through way of negation, that is, through the way of stating what God is not. This negation can and will be said in regards things which we normally say about God, because, at best our language is analogical in regards the divine nature, and so the negation reminds us of the difference between that which we use to represent God with who and what God is. Dionysius did not reject the need for kataphatic theology, to explore and discuss God in and through our own apprehensions of God, but it was the way he pointed out God’s transcendence and the way he engaged it which left its mark on all Christian theology after him There always is something about God which transcends us and all discussions of God; if we do not recognize this fact, we risk being trapped by our apprehensions of God, literalizing and absolutizing them so as to turn God into what God is not, ending with the creation of an idol which we place in front of God that cuts our contact with God.

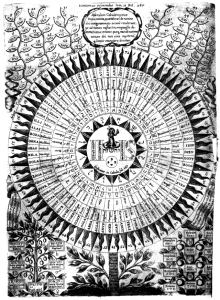

While I understood the reason why Dionysius left room for kataphatic theological reflections, it was my engagement with St. Gregory Palamas which gave me what I believe is the best way to do this kind of work. Palamas developed the complement I needed to make sure I had a method to do kataphatic theology. He understood and accepted the basics of apophatic theology and what it revealed about God. But he also understood if we treat God and God’s transcendence in a way which denies our apprehension of God, God quickly becomes lost to us, turning apophaticism into a kind of agnosticism if not outright nihilism. The solution which he established is that of the distinction between God’s nature (which transcends us, and is incomprehensible to us), with God’s energies (that is, God’s activities, especially God’s activities in relation to us). This distinction between God’s nature and energies was not one which he created – it can be found in patristic authors, and in the later ecumenical councils of the patristic age, but what he did with it was develop it further, to show how important that distinction is, and with it, how important God’s energies are for us and for theology in general. While God’s nature is beyond us, we are not left without help from God, because God engages us, and it is through such engagements, we get to know God and even find ways to predicate qualities or characteristics to God, qualities which form the basis by which we give various names to God. Thus, we can say God exists, God is one, God is good, God is beautiful, God is love, and many similar things, because God’s actions demonstrate the truth of these predications, and it is in and with these predictions we have the basis we need to do proper theology.

Through Dionysius and Palamas, I have gained one of the major foundations for my own theological enterprise (the other being Sophiology, which is itself, a systematic exploration which can be seen to reflect what we come to know God through God’s energies). My theological views, as should be expected, have become refined through the years, and as I study others who have engage the issues which lie behind the works of Dionysius and Palamas. For example, there is Nicholas of Cusa, whose talk about our learned ignorance, represents another way to engage the transcendence of God while acknowledging we can apprehend and learn something about God. But, I have also explored what philosophers and religious thinkers from non-Christian traditions have done with these concerns, from the Platonists, to Hindu and Buddhist thinkers (who have also tried, in their own way, to embrace an apophatic “theology”), and in doing so, found they helped shape the way I deal with the issues at hand.

Mystics, of course, also taught me, both the way of transcendence, but also of the way to apprehend God, to learn something from and experience God for ourselves. They showed me how to look for and find God in and through all things, to find a way to let everything share with me its own way what it has to reveal about God:

When I asked the dog about God, he said, “woof.”

The cat, in return, looked up and said, “meow.”

What more need I say, what greater proof?

Than the moo of the simple brown cow?

The pebble and the stone remained silent,

While the fire with its cackle did decree

As the water was completely compliant,

The truth of God, unbound and free.

The negative mu,

The positive si:

Both show you

To me.

The ”negative mu” in this poem comes from the Zen tradition, where, in various Zen circles, it was asked whether a dog has Buddha Nature. The answer is various koans is “mu,” an answer has a variety of ways to interpret it, including “yes,” “no,” and “yes and no” at once. This is because “mu” reflects the Buddhist exploration of “nothingness” or śūnyatā, and the Buddhist tradition itself says the Buddhist nature is the same as śūnyatā. In this way, the word, in some way, is meant to deny Buddha-nature as being a nature which we possess; it is not to be seen as some sort of essence which is absolutized, but rather, it is seen as the quality of the void which lies behind all things, the void which the Buddha-nature realizes, and so the nothingness which all things can attain in a positive transcendent fashion (instead of the nihilistic reading of such nothingness). The “mu” is a way to express the apophatic denial, making it a “negative” word; it points to the transcendence which lies beyond us, beyond our thought, a transcendence which shows the great potential which lies behind all things. It tells us to look beyond all human conventions, while also recognizing the apprehensions which serve as the basis for those conventions, leading to the “si” or “yes” which comes after the mu. The apophatic and the kataphatic must go together, and through them, we truly learn of God, even as through them, we then have the means (through God’s energies) to give names to God so long as we keep in mind that God transcends all such naming. Indeed, we are called, as Genesis suggests, to name the things we experience, and so to name even God. Since all things, in their own way, can be said to imagine or represent God, all things provide us means to do so, as all things, in their own way, give us one or more names for God – which is why all things are said to be speaking God, giving an affirmations of God which we must engage with a proper apophatic caveat, lest, we turn God into what God is not, and create an idol:

Tell Me My Name

The one who has no end, has no beginning,

And yet, to that one, does my heart sing.

Before all naming, before all appellations,

The one provides us infinite realizations:

Sophia, Glorious Wisdom From On High

Agape, Wonderous Love Draws Nigh:

Agathon, the Good Beyond Reproach,

Kállos, Beautiful is the One I approach.

Your every action reveals you to me:

Each epithet represents an energy:

Triunity beyond comprehension,

You open yourself to my apprehension.

God, light, and eternal life,

Happiness without strife,

Glory without vanity,

The source of all sanity.

You have give me the challenge,

Every day, I barely manage

To add another title

Without making an idol.

* This Is Part LXVIII Of My Personal (Informal) Reflections And Speculations Series

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.