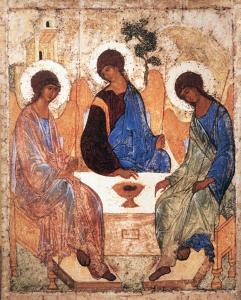

One common hermeneutic mistake many readers of Scripture (and the Christian theological tradition) make is to literalize the conventions used to discuss God (and the persons of the Trinity); they do not understand the words are mere conventions which hint at and point to truths beyond the conventions themselves. The words used to describe God must be understood analogically; they must not be interpreted as meaning the same thing for God as they do for God’s creation. This mistake is why many confuse the use of the term father when used to represent one person of the Trinity (God the Father), or for the divine nature, and think it indicates that God is to be understood as being masculine in gender. Those who make this mistake claim the term father must be understood as it is understood when talking about human fathers, and they say the same is true in regards the term son, that we must interpret the name God the Son as indicating the Son is like all human sons. This is why they say God must be understood as male. This, however, is never how the terms are to be understood, as the Catechism of the Catholic Church indicates by saying God the Father must not be understood as a man or woman, or by any human gender:

By calling God “Father”, the language of faith indicates two main things: that God is the first origin of everything and transcendent authority; and that he is at the same time goodness and loving care for all his children. God’s parental tenderness can also be expressed by the image of motherhood, which emphasizes God’s immanence, the intimacy between Creator and creature. the language of faith thus draws on the human experience of parents, who are in a way the first representatives of God for man. But this experience also tells us that human parents are fallible and can disfigure the face of fatherhood and motherhood. We ought therefore to recall that God transcends the human distinction between the sexes. He is neither man nor woman: he is God. He also transcends human fatherhood and motherhood, although he is their origin and standard: no one is father as God is Father.[1]

No one is father as God is Father, because of course, the term being used is an analogous term; there is a vast difference between how God the Father is father with the way a human father is said to be a father.

It is important that we understand all names, all titles, used for God, even when used by God, come to us as human conventions, conventions which point us to elements of the mystery of God by way of analogy. Those who would suggest we must consider such terms as being “literal” instead of analogical or allegorical must ask themselves what they mean in relation to the term father: literal as to the way ancients understood the term (and with it, the way they understood reproduction), or literal as to the way modern science understands fatherhood (with the way science understands reproduction quite differently from the way it was understood in the in the ancient world). If we say we must understand it as moderns understand the term, then it use could not have been literal for the ancients, but if it is to be understood in the way of the ancient world, then the term cannot be understood literally today.

Christian theology has always pointed out that the way the Father begets the Son must not be understood in the same fashion as creaturely reproduction; those who assumed the term as being univocal with human fatherhood instead of analogical ended up having an Arian understanding of the generation of the Son from the Father since human reproduction is temporal (which is why Arians indicated that there was a time in which the Son was not). This is why one of the major contentions surrounding earlier Christological debates centered upon the Father-Son relationship, and whether it is to be understood the same as in humanity. The Nicene Fathers, like St. Athanasius, made it clear that what we see in the divinity and the generation of the Son has a similarity but also a difference with the terms father and son as they are understood in relation to human reproduction. Thus, they posited an analogical use for the terms. St. John of Damascus, who can be seen summarizing what came from those debates, wrote:

Accordingly, the ever-existing God begets without beginning and without end His own Word as a perfect being, lest God, whose nature and existence are outside of time, should beget in time. Now, it is obvious that man begets in quite another manner, since he is subject to birth and death and flux and increase, and since he is clothed with a body and has the male and female in his nature – for the male has the need of the female’s help. [2]

Again, the fact that the Son is begotten from the Father alone demonstrates the difference between divine and creaturely generation. The terms cannot be understood in the Godhead in the same fashion as in humanity, and indeed, they must not be understood as indicating gender because if they did, God the Father would need a Mother to beget the Son. We must be cautious when engaging human words, human conventions, even those words and conventions employed by Scripture. We must understand they are meant to point us to a truth beyond the convention themselves, to a greater mystery, one which cannot be comprehended by human conventions:

When we come to speak of the Most Blessed Trinity, we are at a loss for words, and yet words must be used to say something of this sublime and ineffable Trinity. To express it adequately is as impossible as touching the sky with one’s head. For everything we can say or think can no more approach the reality than the smallest point of a needle can contain Heaven and earth; indeed, a hundred, a thousand times, and immeasurably less than that.[3]

God engages or acts with us, and through those engagements, gives us the means to speak about various great mysteries of the faith. Revelation comes out of those engagements, and what we apprehend through such revelation is true so long as we engage revelation properly even as it can be false if we employ the wrong hermeneutic to interpret it. We would err if we assume that because God uses our language and its conventions, what is said must be understood as univocal with the way the terms are understood for creatures instead of analogically.

When God uses (or those inspired by God uses) words to represent divine truths, they are meant to engage humanity where they were at, in a way which they could accept. This is why revelation throughout Scripture showed a growing awareness of the transcendence of God, and many things assumed about God earlier were shown, through further revelation, to be false, while earlier revelation still had value as it still pointed to the transcendent truth beyond itself. To grasp the analogy, it is best to understand the context in which a particular convention was employed, and not how we would understand it today; when we do so, we will understand why the convention must be seen as analogical, because we often will see how such conventions have been based upon cultural assumptions, many which have later proven to be false (such as the way human reproduction was understood in the ancient world). Certainly, in our attempts to understand the ancient use of the term, we can end up being wrong, such as we see in the way Richard of St. Victor believed in the superiority of men over women, thinking that was the reason for the use of masculine images for God and the Trinity in Scripture and the Christian tradition:

One ought to note that there are two sexes in human nature, and, for that reason, the terms of relationship are varied according to differences of gender. We call the parent in one gender “father” and in the other gender “mother.” We call the child in one gender “son” and in the other gender “daughter.” However, as all of us together know, there is absolutely no gender in the divine nature. It was appropriate for the terms of relationship to be transferred from that gender that is known to be more worthy to that being who is the most worthy of all. Therefore, you see how conventional language has properly maintained that one of the two persons in the Trinity is called “Father,” and the other is called “Son.”[4]

While Richard was wrong with his understanding of human gender, he was right in affirming that God transcends gender and that there was a cultural reason for why those inspired by God used the terms father and son for persons of the Trinity. Richard tried to give an explanation, which, though is faulty in regards his own conception of the genders, still gives us a possible insight as to how and why Scripture uses the words father and son for two of the divine persons: the authors of Scripture and their contemporaries held a view like Richard, that the masculine was greater than the feminine, so it would make sense they would employ such terms, though of course, we ourselves do not and should not hold onto such an error.

It is vital we give an apophatic no to all the conventions used to represent God. Apophaticism reminds us that with the use of analogy, there is something similar and yet something different from the two analogues, and that difference ultimately is infinitely different so we must deny all affirmations, as represented by Dionysius:

It is neither one nor oneness, divinity nor goodness. Nor is it a spirit, in the sense in which we understand the term. It is not sonship or fatherhood and it is nothing known to us or to any other being. It falls neither within the predicate of nonbeing nor of being. Existing beings do not know it as it actually is and it does not know them as they were. There is no speaking of it, nor name nor knowledge of it. Darkness and light, error and truth – it is none of these. It is beyond assertion and denial. We make assertions and denials of what is next to it, but never of it, for it is both beyond every assertion, being perfect and unique cause of all things, and, by virtue of its preeminently simple and absolute nature, free of every limitation, beyond every limitation; it is also beyond every denial. [5]

Such denial must always point to the way God is always greater and not less than what we can ever think or say about God:

The names which are denied of him are denied because of his transcendence, not because he lacks anything, which is why we deny things of creatures. And so his transcendence defeats all negation. And so neither negations nor affirmations arrive at any sufficient praise of him, to whom belong power and infinite splendor and eternity, forever and ever.[6]

And so, as Richard of St. Victor also explained, we must not confuse the persons of the Trinity with carnal representations:

From these terms, I say, our carnal mind is compelled not to understand anything carnal about the divine generation, but to ascent with our heart toward a higher understanding, and not to conclude rashly anything according to human measure about the mystery of such great profundity.[7]

It would be carnal to misunderstand the conventions used for the persons of the Trinity by thinking they are intended to indicate some sort of gender, either for the persons of the Godhead, or for the Godhead itself. Our genders can be said to flow from God, but God transcends any notion of gender. If we do not understand this, if we try to say the qualities of only one gender apply to God, we have profoundly misunderstood God. It is such a misunderstanding that leads to heresies.

[1] Catechism of the Catholic Church. Vatican Translation. ¶ 239.

[2] St. John of Damascus, “On the Orthodox Faith,” in Saint John of Damascus: Writings. Trans. Frederic H. Chase Jr. (New York: Fathers of the Church Inc., 1958), 180 [Book One, Chapter 8].

[3] Johannes Tauler, Sermons. Trans. Maria Shrady (New York: Paulist Press, 1985), 103 [Sermon 29].

[4] Richard of St. Victor, “On the Trinity” in Trinity and Creation. Trans. Christopher P. Evans. Ed. Boyd Taylor Coolman and Dale M Coulter (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 2011), 322 [Book Six, Ch. 4].

[5] Pseudo-Dionysius, “The Mystical Theology” in Pseudo-Dionysius, The Complete Works. Trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 141.

[6] St. Albert the Great, “Commentary on Dionysius’ Mystical Theology” in Albert & Thomas: Select Writings. Trans. Simon Tugwell OP (New York: Paulist Press, 1988), 198.

[7] Richard of St. Victor, “On the Trinity,” 322-3 [Book Six, Ch. 4].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.