It is Christian belief that the fullness of revelation is not bound to a book, or a collection of religious texts, but is given to us in a person, that of Jesus Christ. He is the God-man, the Logos or Son of God who became man in order to reveal to us that God is love. We are not to understand this love in some sort of abstract fashion, nor that such love can exist as a monad cut off from everything else. Rather, Jesus shows us God is love in a personal sense, and for it to be personal, there has to be multiple persons involved, which is exactly what we learn with the teaching of the Trinity. God is love, always acting in and out of love, first and foremost in eternity, for within the divine nature there are three divine persons who are united as one in and through that love. It is also out of such love that the tri-personal God created the world in order to share it with more subjects. Love does not remain closed off in itself, but rather, so it flourishes in its sharing.

The incarnation was not some secondary, accidental event which happened thanks to sin. God intended creation to participate in and share with the divine life, and in the act of creation, God always intended to connect the two together in and through the God-man. Sin interfered with that plan, and so it had to be dealt with so that the original plan for creation, its deification, could take place. Thus, in the incarnation, the God-Man, Jesus, had to deal with sin, but beyond that, the incarnation also brings about deifying grace, which is why, even without sin, the incarnation would have taken place, so that such deifying grace could be given to world. For the incarnation is the bridge which connects the uncreated eternity of God with creation so that creation can participate in that eternity itself.

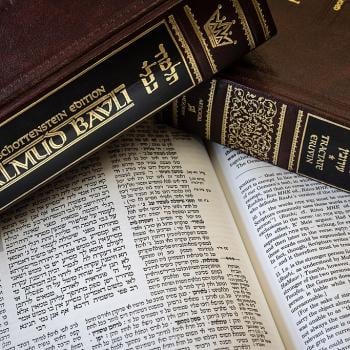

Christian Scripture, which of course, borrowed from the Jews and their Scripture, represents a key, indeed, central record of the way God is at work with humanity, demonstrating various ways God works, out of love, for the sake of creation. As it deals with, records, and brings into reflection all kinds of ways God’s grace has helped transform humanity and influence history, it is indeed an inspired text, but of course, the inspiration must be understood correctly. It is not a text dictated by God, but rather, it is a text which was written by humanity, taking the inspiration grace gave to it to provide for itself a record it can use to look back and reflect the ways God has been at work with it. It allow us to see the progression of our knowledge and understanding about God, our growing awareness of who and what God is thanks to God’s encounters with us. As that progression is tied to the incarnation, Christians interpret all Scripture in its light, even if others, without such a hermeneutic, will still be able to learn from and it all kinds of truths about God and God’s ways with humanity. Scripture shows us humanity wrestling with God, often getting things wrong, and God, then, wrestling with humanity in return, trying to guide and teach humanity along the way.

God continuously encounters humanity where it is at, and in each of those encounters, shows the divine love God has for it, and for the rest of creation. In and through that love, God reveals things which need to be changed so that humanity can better apprehend and engage that love. Thus, for example, early on, due to the awe humanity had for the divine presence, they believed God wanted us to make sacrifices to prove our love. While God could and did accept them, God also wanted us to understand it was not what was wanted, which is why we can see in revelation God was at work, telling us we were wrong to think such sacrifices were needed or wanted. To fulfill that message, God brings an end to our sacrifices by becoming the willing, final sacrifice for us.

When we read any text of Scripture, we can and should try to understand its original meaning and how its original context helped establishes that meaning. Similarly, we should accept that the text, over time, can and will come to be interpreted differently, as new audiences come at it with different contexts, different hermeneutical lenses. Thus, what is seen as the meaning of the text will change over time, and there is nothing wrong about that. God’s ongoing revelation to the world means our interpretation of what happened in the past will change as that revelation itself changes out context and our hermeneutical lens. Thus, for the Christian, the whole of Scripture, the whole text, is to be interpreted and understood in light of the incarnation and the revelation of God’s trinitarian love, even if at times, we find it difficult to do so. And it is in this fashion, we can begin to see how one God is at work throughout Scripture, one and the same God, even if some times, the authors of Scripture seem to contradict each other due to the different contexts in which they wrote their texts. What we need to do is find out how to connect the texts together, to recognize, as St. Augustine said, it is one and the same God being engaged throughout Scripture:

The God of both Testaments is one. And just as the texts we have quoted agree, so do those that remain, as you would see were you willing to consider them carefully and with unbiased judgment. But because many things are expressed in the homely language accommodated to simple and uncultivated minds, so that they might rise through human things to the divine; and other things are expressed figuratively, so that the zealous mind, having exerted itself to discover their meaning, might rejoice more fully having found it, you abuse this admirable purpose of the Holy Spirit in order to deceive and ensnare your followers. [1]

When we think back to our youth, we will see how we often thought our parents were being mean to us not giving us what we wanted. We might have even told them they must not love us, because they did not give in to our demands. If we wrote about them at that time, since we would not have understood what they were doing and why they were doing it, we would have portrayed them as having little to no love for us. We would have represented them as being cruel and tyrannical. Looking back, we can see things in a new light. We can see the events we would have written would have happened, but our understanding of them would have developed. We will understand more was at work, more was at play, than what we understood as a child. Thus, if we wrote about those events, once as a child, and later an adult, our description and presentation will be quite different. And while, as an adult, some aspects of what happened might not be so fresh in our mind, and so we might not be able to put down the fact as well as when they happened, our understanding of the event will be greater, and provide us much more insight. We will be able to see and discuss the great, patient love our parents showed to us when we were not so patient our loving ourselves. If someone were to read accounts from our youth and from our old age, they might think the accounts are radically different, that the portrayal of our parents are so contradictory, they can’t both be seen as truth. This is exactly what it is like when people try to read Scripture without understanding the way revelation was proceeding in and through its authors.

Scripture is the history of humanity’s growing encounter and awareness with God, giving presentations of it at different stages of that encounter, each, therefore, appearing to represent God differently. Each text represents the same God from a different angle, some with better appreciation and understanding of God and what God is doing than others. And when we understand this, then, when we read older texts of Scripture, we can read it in and through our greater awareness of God, of what we have learned in and through the incarnation, allowing us to read the events recorded in Scripture and come to an understanding of them which was different from those who wrote about them, and yet, we must rely upon those text to learn of those events so that we can interpret them in a new light. We can see, therefore, that the original presentation was a presentation of the truth, but one which must not be taken as an absolute, or even necessarily, literal presentation of it (especially as early Scripture writers wrote with a more mythic than empirical understanding of history). This is why it also must be said that: “Nevertheless, we see that the Torah is not absolutely determined by one view but by the wills of those who comprehend and cleave to it.”[2] There is not one view to the Torah, to Scripture, but many, as they are many ways to engage it and learn from it. Certainly, we can pit texts within Scripture against each other, if we want; and certainly, many authors of the texts would likely find themselves often challenging and disagreeing with each other, but this does not mean there cannot and should not be seen a way to bring it all together. The Christian faith believes there is, and that way is in and through Jesus. They believe all of Scripture, indeed, all of history, points to him, both what happened before the incarnation, but also what happened after. This is why Christianity engages typology and allegory, for they help us see how Christ is being revealed in all of Scripture:

With Jesus, in fact, these events of the end, of the fullness of time, are now accomplished. He is the New Adam in whom the time of the Paradise of the future has begun. In Him is already realized the destruction of the sinful world of which the Flood was the figure. In Him is accomplished the true Exodus which delivers the people of God from the tyranny of the demon. Typology was used in the preaching of the apostles as an argument to establish the truth of their message, by showing that Christ continues and goes beyond the Old Testament: “Now all these things happened to them as a type and, there were written for or correction” (I Cor. 10, 11). [3]

We must not use our understanding to undermine other engagements with God, and with it, other engagements with the Torah or the Tanakh. There is a wealth of inspiration which can be found in and through the engagements with God presented in it. This is why those who hold to it, even if they are not Christian, have much to say about God, much which Christians should listen to. To be sure, Christians should engage what they learn in this fashion with a Christian hermeneutic, to see how it can still be connected to the Christian belief that revelation is centered upon and comes to its fulfillment in Jesus. And, because Scripture, special revelation, starts with the people of Israel, they should always be cherished by Christians instead of being abused, mistreated, or denigrated by them. Christian should not undermine their continuing religious experience, and the writings their religious leaders and mystics have left us to study and contemplate. For, within them, we still see God is at work in and with them. They are dealing with the grace which was shown to them when they were chosen to have a special place in salvation history, a grace which still inspires them and their religious lives today. Yes, Christians will have profound disagreement with them from time to time, but even that disagreement must be seen as coming from a deeper, greater unity, for their history is intricately connected and tied with the history of the Jews. This is one of the many reasons why it is wrong for Christians to be anti-Semitic, to be hostile to them, for such hostility ultimately undermines the root of grace which God established in and with them (others, of course, deal with the errors of racism, and the fact that all humanity deserves to be respected). And, in the end, such hostility ends up becoming a hostility not only against them, but against God (as can be seen in all the early-Christian “gnostic” sects which wanted to deny the value of the Tanakh, as they denigrated not just the texts, but God, by calling God evil). Thus, in order to honor and respect God, and all they have learned, Christians should honor and respect the people of Israel, the Jews, even as they should respect all people and all that God has done in and with all the people of the world.

[1] St. Augustine, “The Way of Life of the Catholic Church” in The Catholic and Manichaen Ways of Life. Trans. Donald a. Gallagher and Idella J. Gallagher (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1963), 26.

[2] Isaiah Horowitz, The Generations of Adam. Trans. Miles Krassen (New York: Paulist Press, 1996), 205.

[3] Jean Daniélou, SJ, The Bible and the Liturgy (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1966), 5.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.