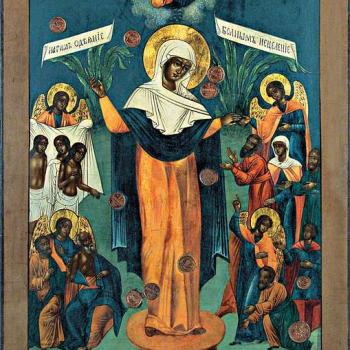

To continue our discussion on why Mary is to be seen and honored as the Mother of God (See Part I and Part II here), we must engage a discussion on the person of her Son, Jesus, the God-Man, and explore a part of the paradox which develops because Jesus is both God and Man.

In the incarnation, the eternal Son, God the Word, assumed temporality unto himself as he became man. And yet, despite this, we say that he, God the Word, is not changed and does not change. How is this possible? He is God, and as God, he must be what God is, and God does not change. “”For I the LORD do not change” (Mal. 3:6a RSV). This is confirmed in the book of Hebrews, in which the author states without equivocation, “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and for ever” (Heb. 13:8 RSV).[1] But by the assumption of humanity, which must seen as included in the eternal act of God the Son, the humanity itself is created in time, and exists in time, and is changed in time. Jesus, in accordance to his humanity, does change: he is born, grows old, moves, eats, sleeps, teaches, prays, becomes silent, is taken up on the cross, dies, and finally, is resurrected in glory and ascends into heaven.

What is important for us here is that he was born in time, that it was one of the many temporal changes which the eternal Word assumed to himself. How can he who is said to be unchanging and ever the same also be said to experience change? The answer, which we have already suggested above, lies in the way the eternal Word assumes humanity: he assumes it in his eternity, that is, in accordance to his person, his humanity is assumed by him in and through his one eternal act; the assumption of humanity is not a change in who he is, for it must be seen as a part of the eternal identity of God the Word.

For us, who exist in time, we see and experience not only the work of the Word in a temporal fashion, but all that God does as well. It appears that God is constantly changing, but in reality it is we who are changing and gaining different perspectives and experiences of the one unchanging act of God. We must not confuse our perspective, and how God seems to change in relation to our changes, with any real change in God. And so, though the Word assumed humanity and acts in time in and through his humanity, and therefore changes in time in accordance to his humanity, he is still the one unchanging Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father before all ages. Jesus is the Lamb of God slain from the foundation of the earth (cf. Rev. 13:8), showing how his death is in the Word in eternity, while in time, he is slain at a particular time and place, manifesting that eternal action of the Word. The eternal Word experiences all he did in time in accordance to his humanity in and with his eternal activity, which explains why all that he did is capable of being said, in conventional terms, to be predestined from all eternity.[2]

When looking to God, we must see that his existence is his one eternal, perfect act. Because of its perfection, there is nothing to change in it. His potential is completely actualized in and through his activity. There is no room for change or improvement, for he is perfection itself, his existence fully realized in his perfection. Yet, God in his action transcends us, and we experience that one simple eternal action within our temporality, changing our experience and understanding of it as we find ourselves constantly encountering it again and again in time. God is not changing, but our experience of God is changing, making it appear that God changes when he does not, a point St. Bonaventure beautifully expresses by saying:

Although the first principle is immense and infinite, incorporeal and invisible, eternal and immutable, yet it is the principle of things spiritual and corporeal, natural and by way of grace, and hence it is also the principle of all things mutable, sensible, and finite, through which it makes itself known and manifest, though in itself it is immutable, non-sensible, and infinite. However, God makes Himself manifest and known in general by the universality of the effects emanating from Himself, in which He is said to exist by essence, power, and presence because He extends Himself to all things created. He makes Himself specially known by other effects which lead to Him in particular and because of these effects He is said to dwell in, to appear, to descend, to be sent, and to send. [3]

Reflecting upon the relationship between time and eternity might help us understand this better.[4] Time is embraced by eternity. All that emerges in history with its succession of temporal moments is contained by eternity. Time is the realm of becoming, of change. God, who is eternal, true being, is not contained by time: he made time so that he is beyond time, albeit because time exists in the space God gave it within his eternity, all of time is within the presence of God. What happens in time for those within time is experienced temporally in a succession of inter-connected moments, each which reflect and bring to light an aspect of eternity; but all of what is done in and through those moments is seen by God in his simple, unchanging eternity as a compounded unity which has a beginning and an end and which he observes in eternity and transcends in that eternity. What is in time merges with him as it comes to its end and finds its place in God’s eternal order. Jesus is the mediator or bridge between the two, for as God and man he is eternal and within time. Jesus’ in time, through the incarnation, therefore brings him to work with his creation it its temporal order, but through his ascension into heaven, he takes it all back with him to its final and proper place in eternity.

Thus, we have a basic way to express the relationship between God and time. Yet, we need to mention a few more aspects of that relationship. God is an unchanging act, yet as has been said, that act is acting with us in in time. It is because what is in time is made by that one eternal act of God, given life of its own by that one eternal act, that it is allowed to express itself and reveal itself in relation to how it acts with and responds to God. He created the whole of time to reflect the choices made by those living in time, giving them freedom to express themselves within his eternity. The very act of creation, both in its initiation and in its preservation, should be seen as contained within the eternal action of God, where what is done and established by him in time comes about through his one eternal knowledge of what he knows we have chosen to do in time: his giving over creation to time presupposes his eternal knowledge and gives God’s eternal answer to our temporal activity. Thus, what happens in time is not for God a change in his act, even if, for us in our subjective experience, it is. All that God reveals in creation is experienced by us in their becoming and ceasing to be, by their beginning in time and their ending, that is, by the succession of moments which point to eternity.

A moment of time is a mere piece of eternity, and so, in time, we grasp elements of the eternal act of God, but in eternity, in God in his divine simplicity, all such acts are not divided. As such, all such acts are reflections of the eternal activity of God even though they appear to be temporal for us. This is true for all persons of the Trinity, but especially for the second person, God the Son, who is the eternally begotten Son of the Father. The divine Son in his eternal act assumed human nature and through it personally united himself with time. God the Son is eternal, but experiences and knows time through his humanity; his temporality does not overcome his divinity and his eternity, but rather, demonstrates how that eternity is at work in time. Time is shown to be real, not illusory, through the incarnation:

For can one deny the reality of time when in the fulfilled times and seasons God was incarnated, when the nativity of Christ occurred, when his earthly life transpired, and his resurrection and ascension were accomplished? If eternity is clothed in temporality, then time also proves to be fraught with eternity and generates its fruit. It is therefore necessary to accept that between time and eternity there is correlativity – time is grounded by eternity; but in this there exists a hiatus between them, for eternity is transcendent to temporality, it opposes becoming. [5]

More to Come

[1] The person of Jesus Christ, God the Word, does not change. It is one of many ways which Scripture indicates Jesus’ eternal nature, and therefore his status as God. What is eternal does not change, but what is created or made does change. For anything which was made or created, the act of being created itself is indicative of change, indeed, the first change, going from non-existence to existence.

[2] See, for example, Peter Lombard, The Sentences. Book 3: On the Incarnation of the Word. trans. Giulio Silano (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 2008), 36 [III-vii.2]

[3] St. Bonaventure, Breviloquium. trans.Erwin Esser Nemmers (St Louis: B. Herder Book Co., 1946), 33.

[4] As this is not the fundamental core of our address, we will explore the concepts briefly here; it would take us far astray to give the concepts of time and eternity justice. What follows is only a brief outline, with the weaknesses associated with such a discussion presupposed.

[5] Sergius Bulgakov, Unfading Light. trans. Thomas Allan Smith (Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdman’s Publishing Company, 2012), 206-7.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing