Why Every Reading Is Interpretation: The Hidden Process

Every time we read a text, we are interpreting it. No matter what the text is, no matter how simple it seems it should be for us to understand what its author wants us to know, we still have to engage some sort of interpretive process to get that meaning. Often, we are unaware that the process is happening as it is automatic, making us think there is no interpretation going on. This is why many, especially fundamentalists, think any question they are given about the meaning of a text is answered by showing the text itself. In reality, everyone takes all kinds of assumptions with them as they read a text, assumptions which might change as they read the text, to be sure, but nonetheless assumptions which influence the interpretation process, making those assumptions serve as the hermeneutic lens they use to understand the text itself.

Hermeneutical Work

When reading texts written in other languages than the one(s) they know, a reader has to rely upon the interpretation(s) of its translator(s), because its translator(s) will have to decide what the author intended with the text in order to decide which words which best approximate and represent the original text. Sadly, many readers do not take this into account when they read a text in translation; they assume there is no interpretation going on in the process of translation, just as they assume there is no process of interpretation going on in their reading of the text. Even texts written in a reader’s own language, but from a different historical or cultural standpoint, will require them to do some hermeneutical work if they want to understand the text as it was originally meant to be read and interpreted.

Multiple Meanings

Thus, it is very important for us to be honest with ourselves; we must accept that every engagement we have with a text has us interpreting it as we read it. If we are conscious of this, we can better engage the text, as we will be able to raise various questions concerning the text, questions which will help us determine the author’s original intent instead of assuming the way we unconsciously interpret the text represents that intent:

In fact, the only way we can understand texts is by interpreting them, and the richer, more complicated, and distant from us by language and culture the text is, the more necessary and complex will be the required process of interpretation. The question is not whether we will interpret the text, but how. The refusal to interpret is a particular kind of interpretation and one which is not justified by our human experience with texts and reading. [1]

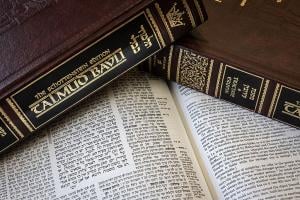

Those who cannot read the original language of a text, especially if the text is ancient, and from a culture far different from their own, they should read as many translations of the work as possible. Each translation will add to the many different possibilities for them to consider, many different ways to understand the text, with each translation given a nuance the others do not do. Translations, in this fashion, should be seen to complement each other. We must not assume any one translation is perfect, nor that any translation which differs from our favored translation as being bad (or wrong); rather, we must understand each translation represents a possible meaning which can be had from the text, a meaning which, again, comes in part from the translator and their interpretation of the text. Indeed, sometimes the original author might have wanted their work to have multiple meanings, and the best way to represent that is to offer many translations, each based upon one of those meanings. Pavel Florensky suggested this was the case with poetry:

We are also aware that, just as several translations of a poetic composition into another language or languages not only do not interfere with each other, but on the contrary actually complement one another, even though none of them can fully take place of the original, in the same way, scientific representations of the same reality can and must be multiplied, and this does not obstruct the truth in any way. Knowing this, we have learned not to criticize any given interpretation for what it does not give us, but to be grateful each time we are able to find a way to use it.[2]

This should help us understand why interpreting a holy book from any religious faith is difficult; when dealing with a faith which is not our own, we might have a bias which we impose upon our reading of the text, one which looks for the worst possible interpretation possible. On the other hand, when reading our own religious texts, the bias we have will come from tradition, from the way we have come to know and understand our religion apart from the text itself. If we acknowledge this, we can begin to explore various holy texts differently, maybe not completely neutral, but at least in a way so as to move beyond our own biases and try to understand the text based upon the context in which it was written. To do that right, we will have to do research, learning as much as the author’s context as possible. We should try to find out, if we can, when it was written, why it was written, and the audience to which it was written. We will have to try to learn how to think like the author thought by knowing the language they wrote in, and in accordance to the time and place in which the author lived, and the kinds of social and cultural beliefs they held. Even then, at best, what we will attain is an approximation of the author’s original intention with the text. Most people will not be able to do this, if, for no other reason, they won’t have the time necessary to do all the research necessary; when that is the case, they should accept the limitations this creates, knowing that it means they should not assume too much from their reading of the text. Of course, for religious texts, many will point out that it is meant to be a living text, that God is at work in and through it so it not only is to be interpreted the way it was originally intended to be interpreted when it was written, but it can be adapted to meet new situations, creating meanings that the human author did not intend. Even when this is the case, they still should be able to point out and acknowledge the evolution of meaning going on over time and how their current reading of the text might differ from what the original author intended.

Learn From Engagement

Thus, when we read a text, we must accept as a simple fact, we interpreting it as we read it. If we recognize this, we can be better readers, as we will more carefully consider how we are interpreting it as we read it. Indeed, we might take the time to try to discern various ways to interpret it, and not just the one way which is most obvious so us. This will give us multiple interpretations, multiple readings, of a text, each giving us something more to consider in the process, and when it is a text which we believe is invaluable, something meant to teach us or reveal to us something beyond our normal experience, such as a holy text, this certainly should be something which we would want, because then we will learn something from our engagement of the text instead of just using the text as a kind of pretext for our own assumptions.

[1] Sandra M. Schneiders, Beyond Patching. Revised Edition (New York: Paulist Press, 2004), 41.

[2] Pavel Florensky, Imaginaries in Geometry. Trans. Anna Maiorova and Karen Turnbull. Ed. Andrea Oppo and Massimiliano Spano (Milan: Mimesis International, 2021), 20.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.