It is sad to see many Christians believe that temporal existence has little to no real value because they think the only thing which matters is what happens to them after they die. To be sure, they have been made to think this by the way many theologians engage the question of evil. When they suffer some wrong in this world, when they see the evil prosper and the good suffer, they are told that everything will work out in the end, that true justice will only be found in eternity, and so they should be concerned only with their eternal fate and not be too concerned with what they see happening in the world. While there is some truth involved with such an answer, it is only a partial truth which is being used and exploited to have people ignore temporal injustices. Justice certainly will be had in eternity, but justice still is meant to have a place in the temporal order. The incarnation shows us that the kingdom of God, heaven, is not absolutely cut asunder from the earth; the two have been joined together – God has come among us, into time, and we can and should be able to experience, in part if not in full, the glory of the kingdom of God while we live, making our temporal existence something which we should be concerned about:

Life in the Kingdom, as preached by our Lord, is not simply a reality reserved for a future time. It is available now, to all those who seek and accept God’s nearness. Many Christians do not enjoy the Kingdom as the fullness of reality because the modern mind seeks to analyze it, program it, control it.[1]

The kingdom of God is all around us, it is in and with us, not separate from us:

In answer to the Pharisee’s question as to when the Kingdom of God would come, Jesus replied, ‘The Kingdom of God is not coming with observable signs …. behold the Kingdon of God is within you’ (Lk 17:20-21). While most modern commentators take the greek expression entos hymon to mean ‘among you,’ ‘in your midst’ — that is, present in Jesus’ person – patristic interpreters tended to render it ‘within you.’ From this point of view, the Kingdom is a mystical reality, a divine gift to be cherished and cultivated within the inward being, in the depths of the secret heart. Access to that inner reality is provided by prayer, particularly continual prayer that centers upon the divine Name.[2]

The experience of the kingdom of God in our temporal lives can be said to be a mystical experience. Each person can and will have their own unique experience of it, due to the infinite variety of grace found in it. What is important for us to realize is that it is not something which we will experience only after we die, only in eternity, but also within our temporal mode of being. Indeed, it is something which can be seen and experienced in the ordinary things of the world, because, thanks to Christ’s resurrection, we can experience such ordinary things in new ways, in ways which reveal how they are a part of the kingdom of God and reflect the truth of God in their own fashion:

The Kingdom is the extraordinary within the ordinariness of life; it is help given to the pregnant cousin, the glass of water to the thirsty person, clothing to the naked, caring for someone fallen along the road. These are common images of life, with no extraordinary significance for ordinary interpretation. But as interpreted by those who are reborn of God in the midst of the human race, these images are of the divine, of the extraordinary, because they can stir something deep inside human beings and undo their selfishness and propel them toward the other, toward the transcendence the other represents. [3]

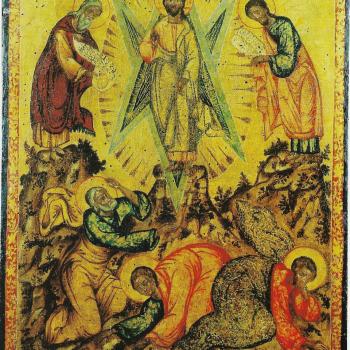

We should open ourselves up to God’s grace, to the light of Tabor; when we do so, we will see the light is not only upon us, in us, and radiating through us, but it is radiating through all things. All things participate in the kingdom of God and are being transfigured by God’s deifying grace. And this is why, it is said, if Christianity is to continue in the world, those who are Christians must become mystics, because mystics are able to take and experience the kingdom of God all around them, and through that experience, help bring that experience to others. We are to embrace that experience, to let it transform us. Then, even those who are not attuned to it will experience its presence by the way we act and live in the world:

The kingdom of God is concerned with friendship and hospitality to those who are not normally “our friends,” to those who are not part of our “circle,” to those who have not means of returning our hospitality – and this is the true test of what hospitality means. Otherwise, it is simply loving those who love us, which is all too easy, all too human.[4]

We are called to participate in the kingdom of God, to do so now, and not just in our future, that is, after we die. We should not wait for its coming as if it is something which is not already with us. Thanks to the incarnation, the eschaton is immanent. Through baptism, chrismation (confirmation), and communion, we partake of the immanent eschaton, letting it enter into us and transform us. The kingdom is all around us. We are given time to partake of it, to experience it, and to share what we have received with the world, helping the world and all that is in it find their place in the kingdom.

We should look at all created things and see how the kingdom is manifest in them. We should look for the kingdom in all things, especially in the little things, in the ordinary things of the world. We should engage what we find, each in our own unique way, due to the unique calling God has for us. Some of us will find that our apprehension of the kingdom of God will make us more active in the world, as can be seen in the lives of those who promote social justice, even as others will find their experience will have them become more contemplative in their spirituality, such as seen in those who become poets. The key is to realize our temporal existence is not meaningless, that justice in the world around us is not meaningless. The kingdom of God is with us, and with it, we can find all kinds of meaning for our lives.

[1] Archbishop Joseph Raya, The Abundance of Love: The Incarnation and Byzantine Tradition (Combermere, ON: Madonna House Publications, 1989; 3rd ed.: 2016), 138.

[2] John Breck, ”Prayer of the Heart: Sacrament of the Presence of God,” in The Contemplative Path. Ed. E. Rozanne Elder (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1995), 44.

[3] Ivone Gebara and Maria Clara Bingemer, Mary Mother of God, Mother of the Poor. Trans. Phillip Berryman (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1989), 34.

[4] Terry A. Veling, Practical Theology (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. 2005), 47.