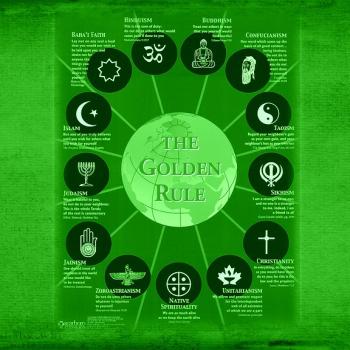

Many people, upon hearing the term “interfaith” or “inter-religious” dialogue, misunderstand what exactly is being discussed. They think it is some sort of dialogue with the goal of creating a new, syncretic religion formed as a composite created by the various religious traditions which have come together for dialogue. That is, they think inter-religious dialogue aims for the establishment of a new religious faith. Many Christians, therefore, consider inter-religious erroneous, because they think it seeks to create an alternative religion, indeed a rival, to the Christian faith. The problem with this understanding of inter-religious dialogue is that it assumes one kind of objective possible from inter-religious dialogue. While it might be true that some involved in inter-religious dialogue desire to establish such a meta-religion, the construction of that meta-religions is not the normative goal or intent behind most inter-religious dialogue. What inter-religious dialogue generally seeks is something much simpler: for members of differing religious faiths to come together, to share with frankness and honesty, the teachings and practices of their respective faiths, and to seek a more harmonious and charitable relationship with each other as a result of such dialogue.

Many people, upon hearing the term “interfaith” or “inter-religious” dialogue, misunderstand what exactly is being discussed. They think it is some sort of dialogue with the goal of creating a new, syncretic religion formed as a composite created by the various religious traditions which have come together for dialogue. That is, they think inter-religious dialogue aims for the establishment of a new religious faith. Many Christians, therefore, consider inter-religious erroneous, because they think it seeks to create an alternative religion, indeed a rival, to the Christian faith. The problem with this understanding of inter-religious dialogue is that it assumes one kind of objective possible from inter-religious dialogue. While it might be true that some involved in inter-religious dialogue desire to establish such a meta-religion, the construction of that meta-religions is not the normative goal or intent behind most inter-religious dialogue. What inter-religious dialogue generally seeks is something much simpler: for members of differing religious faiths to come together, to share with frankness and honesty, the teachings and practices of their respective faiths, and to seek a more harmonious and charitable relationship with each other as a result of such dialogue.

Inter-religious dialogue is not to be seen as a religious form of Christian ecumenism. Ecumenism seeks the restoration of Christian unity. Inter-religious dialogue does not, in and of itself, seek unity among religions. Those engaging inter-religious dialogue might do so, but even if they do, there are many ways this can be done. Some could seek a new meta-religion, but most often, those seeking for some sort of religious unity will do so on the basis of their own faith, showing how and why they think their faith fulfills the expectations and desires of the others and should serve as the unifying religious bond, which is what Nichola of Cusa suggested with his classic, De Pace Fidei (written in 1453).

Nonetheless, it must be made clear, though some who engage inter-religious dialogue seek some sort of religious unity established through it, this is not the goal of inter-religious dialogue itself, and many who engage inter-religious dialogue have no such vision or hope for such a result for their dialogue with others. They want to learn of the beliefs of others and to share their beliefs, so that all can become better informed, allowing unjust prejudices various people have of other religious faiths to be overcome. Inter-religious dialogue can sometimes engage inter-religious worship, though this, again, is not a necessary component of the dialogue, especially since some participants in the dialogue are rather exclusive in their notion of worship. But even without seeking a meta-religion or seeking to worship together, the benefit of inter-religious dialogue is great, because it allows a better understanding and appreciation of the different religious faiths, the different variations possible in those differing faiths, and finally, allows people to see how they can work together in harmony with each other without losing themselves and their faith in the process.

We can see this represented in the original World Parliament of Religions from 1893, where members of religions from all around the world, including Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant Christians, came together to speak to each other and reveal to each other their own particular faiths. In doing so, many triumphalist, exclusive, indeed, racists claims were presented alongside more humble, universal claims, with each tradition, each speaker being given respect even if their view and beliefs radically contradicted what the next speaker believed. For example, Henry Harris Jessup, a Presbyterian minister, was able to speak of how and why he thought the Anglo-Saxon Protestant tradition was superior to all others:

Was it an accident that North America fell to the lot of the Anglo-Saxon race, that vigorous Northern people of brain and brawn, of faith and courage, of order and liberty? Was it not the Divine preparation of a field for the planting and training of the freest, highest Christian civilization, the union of personal freedom and reverence for law? This composite race of Norman Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic blood, planted on hills and valleys, by the rivers and plains, and among the inexhaustible treasures of coal and iron, of silver and gold, of this marvelous continent, were sent here as a part of a far-reaching plan whose consummation will extend down through the ages. [1]

We can see, behind Jessup’s belief, a racist claim, because he thought and taught that some races were superior to others, with the “Northern races” favored by God:

The highly favored Northern races are called by every prompting of the law of love to go to the help of the less favored continents of the South. Christ bids the strong to help the weak, the blessed to succor the unblessed, the free to deliver the enslaved, the saved to evangelize the unsaved.[2]

And so, those of the Anglo-Saxon lineage, those who were blessed with the English tongue, were said to have the greatest, indeed, the noblest, calling from God:

But no nobler service has been given to any people, no nobler mission awaits any nation than that which God has given to those who speak the English tongue.[3]

This is hardly the talk of syncretism, but it is the kind of talk which is possible in inter-faith dialogues. Thankfully, the racist ideologies of Jessup have for the most part been rejected by mainline Protestant traditions, but yet, in inter-religious dialogue, if some partner in the dialogue has such exclusive views, it is viewed better to let them reveal those beliefs than to hide them and give a false impression of their faith and values. Inter-religious dialogue relies upon honesty, no matter how difficult the honesty might be; it especially expects that honesty to be about one’s own faith and beliefs (so that one can humbly learn from the other instead of prejudging them by one’s own prior expectations).

Similarly, therefore, the Catholic contingent at the first World Parliament of Religions had John Cardinal Gibbons speak of the Catholic faith, making it clear he believed it presented the fullness of the truth. For this reason, his presence at the Parliament was not to learn the truth from others but to share the truth which he believed he had with them:

The object of this Parliament of Religions is to present to thoughtful, earnest and inquiring minds the respective claims of the various religions, with the view that they would “prove all things, and hold fast to that which is good,” by embracing that religion which above all others comments itself to their judgment and conscience. I am not engaged in this search for the truth, for, by the grace of God, I am conscious that I have found it, and instead of hiding this treasure in my own breast, I long to share it with others, especially as I am none the poorer in making others the richer.[4]

Nonetheless, he saw there was good to be achieved in the Parliament, because it helped establish goodwill between the people of differing faiths: “Let us do all we can in our day and generation in the cause of humanity. “Every man has a mission from God to help his fellow-being. Though we differ in faith, thank God there is one platform on which we stand united, and that is the platform of charity and benevolence.”[5] Here, he was right to speak of how inter-religious dialogue is about the increase in charity and goodwill we should seek to have with those of other faiths; it is not to hide our faith from them, nor is it about trying to convert people to our faith, but it is about mutual awareness and understanding so we can work together for a more charitable engagement with each other in the world, something which most religious traditions desire.

Of course, if someone’s religious conviction includes seeking unity with others in their religion, then they should speak of that desire, reveal it, and explain how and why they think it is justified from their own religious tradition. At the World Parliament of Religions, Christopher Jibara, a representative of the Syrian Christians, surprisingly enough, suggested this, at least in relation to Christianity and Islam:

Asking the members of the parliament, in the name of God, to study with reverence this vital question on the harmony of religions, I hope the time will come when the two great peoples, Christian and Mohammedan, the greatest, the strongest, the brightest, and the riches among all the nations of the earth, may unite in one faith serving God. [6]

While Jibara’s view was not the normal Christian response at the World Parliament of Religions, his voice was welcomed as being one among many expressions, not only of world religions, but of his particular Christian faith, which was, to be sure, unusual in that he saw it was capable of being united with the teachings of Islam:

I assure you also that by the Koran can we understand the Gospel better, and without the Koran it is impossible to understand it correctly. It is for that I believe that God has preserved the Koran and also preserved Islam, because it has come to correct the doctrines and dogmas of the Christians. There is no difference in the book themselves – the Gospel and the Koran. It is only in the understanding of people in their reading of the Bible and the Gospels and the Koran.[7]

While Jibara’s views might be the kind critics of inter-religious dialogue fear and think all inter-religious dialogue is about, the reality that the dialogue is open to all kinds of views and visions being expressed. What people do with what they learn from the dialogue is up to some. Some will use it to be better informed of the other to better appreciate their gifts and talents and beliefs, others will do so to learn of the other for the sake of future missionary endeavors, and of course, some will do so in order to let the beliefs of others seriously challenge them and engage those beliefs to reform their own beliefs (which can then be said to start something else, which is, comparative theology).

Dialogue should not bring fear. St. Paul enjoyed inter-religious dialogue at Mars Hill. This shows not only is it something found at the foundation of the Christian faith, it was something that early Christians thought was a sign of hope, because it meant they were given space to truly present their beliefs to others. Moreover, though Christianity might be better known today and so the need to represent ourselves to others is not the same as it was in the past, it is still important for us, because it is one way in which we can show our love to our neighbor by being there, willing to listen to them as they talk about their own hopes and fears, even as we share ours with them. The Catholic Church understood this when it proclaimed at Vatican II:

The Church, therefore, exhorts her sons, that through dialogue and collaboration with the followers of other religions, carried out with prudence and love and in witness to the Christian faith and life, they recognize, preserve and promote the good things, spiritual and moral, as well as the socio-cultural values found among these men.[8]

Indeed, it is not just people of other religious faiths, but those of no faith, agnostics and atheists, who should have a place in this dialogue, because with them and all others of good will, we can work together for the betterment of the world:

While rejecting atheism, root and branch, the Church sincerely professes that all men, believers and unbelievers alike, ought to work for the rightful betterment of this world in which all alike live; such an ideal cannot be realized, however, apart from sincere and prudent dialogue. Hence the Church protests against the distinction which some state authorities make between believers and unbelievers, with prejudice to the fundamental rights of the human person. The Church calls for the active liberty of believers to build up in this world God’s temple too. She courteously invites atheists to examine the Gospel of Christ with an open mind.[9]

Inter-religious dialogue is important for the modern world. Members of different faiths, and those of no faith, are working together side by side, in the world, showing that they can truly overcome the antagonisms of the past and work for a better future. Ignorance of the other can lead to discord as hatemongering rises from that ignorance, scapegoating people of other faiths for the ills we all face together. Inter-religious dialogue has a key role in overcoming hate, paving the way for a universal brotherhood, as Pope Paul VI said:

Sincere dialogue between cultures, as between individuals, paves the way for ties of brotherhood. Plans proposed for man’s betterment will unite all nations in the joint effort to be undertaken, if every citizen—be he a government leader, a public official, or a simple workman—is motivated by brotherly love and is truly anxious to build one universal human civilization that spans the globe. Then we shall see the start of a dialogue on man rather than on the products of the soil or of technology.[10]

Inter-religious dialogue, therefore, far from being something which contradicts the Christian faith, is one way that the Christian faith can be properly lived out. For by it, bigotry and hatred, such as anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, can be overturned, allowing Christians then to better live out their mandate to love their neighbor. For if Christians are to be known by their love, they need to show that love to others, and listening to others is one of many ways this is possible.

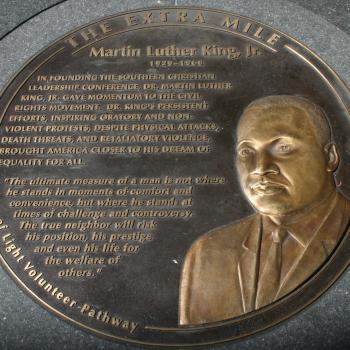

[IMG=4th World Day of Prayer for Peace, Assisi (Italy), Oct 27, 2011 by Stephan Kölliker [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Henry Harris Jessup, “The Religious Mission of the English-Speaking Nations” in The Dawn of Religious Pluralism: Voices from the World Parliament of Religions 1893. ed. Richard Hughes Seager (La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1994), 38.

[2] Henry Harris Jessup, “The Religious Mission of the English-Speaking Nations,” 41.

[3] Henry Harris Jessup, “The Religious Mission of the English-Speaking Nations,” 37.

[4] James Cardinal Gibbons, “The Needs of Humanity Supplied by the Catholic Religion,” in The Dawn of Religious Pluralism: Voices from the World Parliament of Religions 1893. ed. Richard Hughes Seager (La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1994), 157,

[5] James Cardinal Gibbons, “The Needs of Humanity Supplied by the Catholic Religion,” 163.

[6] Christopher Jibara, “A Voice from Syria” in The Dawn of Religious Pluralism: Voices from the World Parliament of Religions 1893. ed. Richard Hughes Seager (La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1994), 199.

[7] Christopher Jibara, “A Voice from Syria.” 200. [He said this after declaring himself to be a Christian who had a professor and a brother killed by Muslims, so that he understood the difficulties involved with his hope].

[8] Nostra Aetate. Vatican Translation. ¶2.

[9] Gaudium et Spes. Vatican Translation. ¶21.

[10] Pope Paul VI. Populorum Progressio. Vatican Translation. ¶73.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook