Abdul Ghaffar Khan, My Life and Struggle. Trans. Imtiaz Ahmad Sahibzada (Roli Books: Greater Noida, India: 2021); 556 + xix pgs.

Most people in the United States have heard of Gandhi, but many, if not, most of them have not heard of his fellow-worker and friend, Abdul Ghaffar Khan (“Badshah Khan”). If they did, they would know of a Muslim who orchestrated a large, non-violent resistant movement, organized, in part, parallel to a military organization, known as the Khudai Khidmatgar (“the servants of God”). They were mostly Pukhtuns (Pathans/Pashtuns) from the “frontier” territory, that is, from what is now parts of India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. They worked with and gave important support to the Indian National Congress and Gandhi, who likewise, often helped them with the resources they needed. Most of them were Muslims, but there were some who were Hindu or of other faiths, which is why, though initiated by a Muslim and mostly engaged by Muslims, it was really an inter-religious organization which worked for one fundamental purpose: to be of service to God by helping develop and promote the good of humanity, and especially, to help those who were oppressed (no matter who oppressed them).

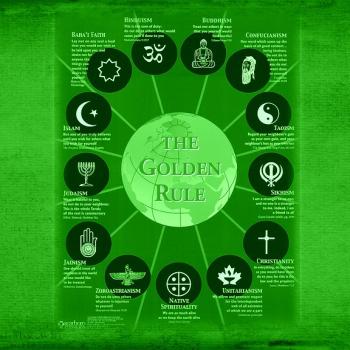

Abdul Ghaffar Khan was himself a Muslim, and even before he formed the Khudai Khidmatgar, he found himself seeking to reform society. In doing so, he found himself criticized and attacked by many of his fellow Muslims. He was extremely interested in the use of education for such reform, starting schools which could and would teach the youth that they did not have to follow outdated traditions which hindered the advancement of society, those which denigrated their human dignity and even hindered what he believed was the central messages of Islam. While he held strongly to his faith, he did not believe Muhammad taught exclusivism, suggesting that only Islam was correct; instead, he believed that the Quran indicated that God had established a variety of religious faiths in the world, and each of them should be respected. He believed that all major religious traditions had, at their foundation, inspiration from God and as such, all of them had something to teach the world. Similarly, because God established them, they had much in common which should lead them to work together while respecting each other’s unique faiths and the differences contained in this faiths. This inclusivism along with the reforms which he wanted to establish within Islamic countries meant many Muslims, especially those in positions of religious or secular authority, did not like him and fought against him, and in doing so, cooperated and worked with British authorities against him.

Thus, Abdul Ghaffar Khand found himself facing two fronts of resistance to his work, one being from the British, and the other being many of his fellow Muslims. It was in part because the Muslim League, and with it, many Muslim authorities did not help him and his mission, but the Indiana National Congress, once it learned of his non-violent ways, were willing to do so, he made his connection with the Congress and Gandhi, giving him an important place in modern history. He felt, however, many of the Muslims were hostile to him, and to others, like the Hindus, even as Hindus were hostile to Muslims, due to British interference. For this reason he also thought working together with the Indian National Congress was a way to resist that interference, to show that Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, and others could and should get along and work together serving God by serving and promoting the common good.

Badshah Khan’s life story is interesting and sad. It is the story of a noble, indeed, one can say saintly man, whose life was one of constant service to God by his constant service to humanity. He tried to establish a better way of life, not just for his people, the Pukhtuns, but everyone, and he was able to bring about some reforms thanks to his work. But yet, like many saints, he found himself facing not only great resistance to what he was doing, but constant set-backs, constant struggles with people who wished him great ill. He also experienced heartbreak when friends and family members, sometimes out of ignorance, sometimes not, betrayed him and his movement, and yet he recognized and accepted that many of them did so out of pressure or ignorance, and that even he could and did make similar mistakes in his life. He wanted Pukhtuns to be united, and as such, he rejected the notion of the partition which divided India from Pakistan. He understood that it would allow some of the worst elements of the British influence, the division and hostility they fostered between Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and others, to continue, and that hostility would end in bloodshed, which it did. His autobiography, My Life and Struggle, written in 1983 at the behest of his friends, has finally been translated into English. While it can be a struggle for a reader not familiar with all the people and events he mentions, it is well worth taking the time to read. It is a tremendous piece of personal history. It reveals many of the horrifying ways the British used to keep themselves in power, showing us the worst of humanity, even as it reveals his own thoughts which developed as a result of his work, giving the reader the wisdom of someone of a life lived well instead of someone reflecting on life merely through academic study and theory, insight which shows humanity at its best.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan, as the leader of a non-violent resistance movement, gave lots of speeches, but he preferred action to talk. He was naturally charismatic, which is why he was able to lead such a large movement, but he was not an intellectual sage who liked to write speeches or books. This is noticeable in the way he recounts his life. One should not expect his autobiography to be a highly polished literary masterpiece; it is not. It doesn’t need to be. Its strength lies in the thoughts and deeds of his life, his ability to remember key events in his life and the people associated with them, as well as his ability to engage thoughtful reflection on them. He will often give lists of names of people whom the reader might not recognize, and sometimes, he gives little to no indication of who they are beyond their name. While some might like to know more, it is still important that he did this, for this shows that all great men and women are great, not just because of the things they do, but because they work in and with others. It is important to remember all those who worked with him to honor them and their deeds as well to make sure they and their lives are not forgotten. Nonetheless, with so many people being mentioned it can be difficult for the ordinary reader to take it all in, so much so that in a first reading of the text, some might take less note of them and more note of the general events being explained. Then, they can go back and pay attention to the people involved, especially if their interest in the book is that of a historian, for here he offers material which they can and will need to write scholarly historical studies. Similarly, for others, it is his thoughts and ideas which might be the most important thing they will get out of the book, and they will be able to get this even if they do not remember all the names he mentions. And, to be sure, his reflections are a highlight of his autobiography because they demonstrate, beyond his deeds, how great a man he actually was. In them, he admits he often made mistakes, recognizing the humility that we should all have, and with it, being more accepting of the mistakes of others. And certainly, among those thoughts, his religious sentiment is of great value, for he shows himself to be a man who was very open to and engaged with inter-religious dialogue. He promoted the study of all major religious traditions. He thought everyone could and should learn from each other. And yet, he remained a Muslim, interested in working with and promoting reform within Islamic society. Indeed, discussions concerning his confrontation of corruption within Islam while still being a strong, faithful Muslims, can help people of all religious faiths navigate similar concerns from within their own faith tradition. Having strong faith does not mean one will have an uncritical faith – indeed, a strong faith will be critical, especially of corrupt religious officials. They will have all kinds of struggles as they recognize both the good revealed in their faith but also see the way that good has been subverted in history. Thus, a person of faith does not have to follow blindly along with what they were told by religious authorities, without, of course, denying the whole of their faith tradition and the value of such authority. We have, with him, a person who not only tried to understand his faith but show ways the faith can be revitalized by overcoming the corruption which hindered its proper form. We can see some of this internal struggle and reflection in various instances in his autobiography, such as when he wrote:

The Prophet of Islam, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him (PBUH), had lit a brilliant light of democracy in Madina. I do admit that this democracy was limited to the city 9f Medina and to the Muslims i.e.. the leader of the Muslims and the successors of the Prophet (PBUH) were appointed on the advice of the companions of the Prophet. There was darkness in the rest of the world. And this lamp remained till the life of Hazrat Umer, may Allah’s pleasure be upon him. After his death, the desire for wealth and power took hold of the Muslims and this light was extinguished and remains so till today. Europe, which was in darkness, lit this lamp there. They were enlightened by it. And the Muslims, who extinguished this lamp, have not been able to light it again. Today, all the Muslim countries of the world do not have democracy. When power was transferred to the hands of the Bani Umaya family, Mawyia rose and changed the status of Muslims (24-5).

The problem, he believed, is that that Islam, like many religions, though its truth continued to be available, became a play-think of the rich and powerful, subverting it. “Every religion, when it falls into the hands of self-seeking people, is not longer imbued with the initial spirit of revelation. It becomes the religion of the moneyed class and exists in mere form.” (84) And that spirit, he believed, was the spirit of love, love for God but also love for fellow humanity. Religion, he believed, taught that we should render ourselves over to God in loving service, but also recognize that such service is ultimately do be done by serving humanity. He believed that all authentic religious revelation at its core serves to bring this about:

Every religion has prescribed freedom, caring for others and tolerance, but they are not aware of this, nor has anyone made them wise to it. The truth is that all revealed religions are from God and have been sent to the world to promote love, affection and for the service, benefit, and comfort of humankind. It is incumbent upon the followers of every faith to remove hatred from the hearts of humankind and instil in them love and affection – so that they can be of assistance to each other. But we have not been made aware of this by anyone (16).

It is easy to see how, with such a spirit, such an understanding of religion, he could, and would find himself studying and learning from all religious traditions. This was something he found himself doing especially while he was in prison, when he was in contact with people of differing religious faiths and they had the time and ability to engage such discussions and learn from each other. But, as love and the promotion of human dignity and freedom is what he believed was at the core of Muhammad’s teaching, he also taught that where such freedom, and promotion of human dignity was lacking, the authentic teaching of Islam was in decline, often being held back by those in positions of power and authority. He saw tradition often became the means by which this was done, that it reified some cultural ideology which ended up standing against the promotion of human dignity. He saw this in the way many Muslim societies treated women; their human dignity and equality with men was being denied to them as they found themselves forced to live in conditions which kept them ignorant and bound to the whims of their husbands. Thus, one of the many social reforms he promoted was in regard women and their status in society, helping them get education, teaching them that they could and should have a place in secular society just like men, and helping them realize they did not have to be forced to follow traditions, like wearing a Hijab, which he saw ultimately served to control them instead of help them:

I had a lot of respect and sympathy for the honour of our womenfolk because, unlike other nations of the West, we had no respect for our women. They were considered inferior to men, although inferiority and superiority are solely dependent upon one’s deeds. Those whose deeds are bad should be considered inferior, irrespective of gender. If a woman performed good deeds, then it was only right that she should be considered superior. God has created men and women to populate the earth, as equal companions(53).

Sadly, many of the women he wanted to help resisted it because they were raised to believe and accept those traditions:

I would always try to remove the sense of inferiority from the minds of the women, which had been inculcated in them by ignorant and selfish men. I would argue with my wife that men and women were equal in the eyes of God, and that honour and dishonour depends on one’s deeds. I would also tell her that women themselves were responsible for their inferiority complex because they viewed their sons and daughters differently and instilled in their daughters’ minds that God had created men superior to women and that sons were more important than daughters (55).

There is much of this kind of thought within this phenomenal book. There is a lot of religious reflection in it. However, most of the book deals with historical events, telling us accounts of the many times he was arrested, and the poor treatment and abuse he and other political prisoners faced while imprisoned. He also recounted the way he and his associates worked together to confront the British stranglehold on society, but also, how the British worked to undermine their cooperation, so that in the end, they helped bring about a resolution which he thought was detrimental to all (the partition between India and Pakistan). He made it clear, not all who were involved in jailing him, not all who worked with the British, were mean or cruel, even as he was able to show how many of his allies ended up not understanding all the lessons they could and should have learned from the way things were badly run and manipulated by the British. Many who joined his movement did so for selfish reasons and ended up harming the movement itself. Nonetheless, he was willing to endure it all, even endure betrayal, if he thought in the end, what he did would be of service to humanity, to help make things better. It is this spirit which is lacking with so many who create or work in reform movements, and it is this spirit which is necessary for them to actually be of service to humanity. And it is this spirit which makes him so noble and worthy of honor, an honor, sadly, which seems to have been denied him by many in Western society. He was, in many respects, a nobler man than Gandhi, but he had also been a man who has not had as much written or revealed about him, so that many do not know of him and his contribution to history. This book, his autobiography, helps rectify this situation, even if he only recounts his life story up to 1947 (he died in 1988). His message is a universal message; if only more people could hear it and live it out:

We Pukhtuns consider ‘God’s work’ and ‘service’ as that which is being undertaken for the sake of God, without any expectation of personal gain. Since God is not in need of our service, it is His creation (humanity) which stands in need of service (231).

This is what we should all be doing. We should be serving humanity, not with selfish interest, but with selfless love. And his story is one which shows that selfless love can affect a great deal of change, but also, one which shows that engaging it will lead to all kinds of resistance and set-backs. We should be honest with our expectations. We should always hope for the best, but also understand, we cannot create utopia, and that many things that we do will be forgotten. We should not be doing it for the memory or the honor, however, so if we are forgotten, but help make things better, we should find that to be due reward. The struggle which love promotes, the struggle to make for a better world, is a constant struggle. It will, as his life shows, experience all kinds of betrayals, but they should not stop someone from pushing on, just as he, in the end, felt betrayed by the India National Congress for is support of the partition did not mean he felt he could and would stop his work for reform (and recognize the good which they did for him). He didn’t stop doing what he could for his people. Even after the British left, he found himself constantly struggling with the powers that be, and so constantly imprisoned. But he does note that if his friends had listened to him and did not accept the partition, he believed things would have been far better:

We, the Khudai Khidmatgar, had tried our best to bridge the differences between the Muslims and Hindus; and no matter where I was in Hindustan, I tried my utmost to attain this objective to create affection and unity between the Muslims and Hindus; and to remove hatred and enmity from them. Whatever we had managed to achieve, it has all been allowed to be swept away from the flood. In Pakistan, what brutality the Hindus and Sikhs had to bear; and in Hindustan what are the Muslims going through? Such a lot of hatred and enmity has been generated, that all hopes of reconciliation have been dashed, giving birth to many problems (497).

But even though he felt much of what he worked for ended up in failure, his life was not a failure. He continued his work all his life, and what he started, continues to help shape the world today. We must recognize that the work of love is an ongoing work. It is something handed down to us and is something which we will hand off to those who come after it. It will be a work which will continue until the end of time. It will constantly find itself in a struggle between those who promote the common good, and the peace and justice which it offers, and the private good, and those who selfishly want to keep the good things of the world like wealth and power for themselves. That struggle can be and is a religious struggle, though of course, one doesn’t have to be religious to engage it. We can and should learn from the past, for by it we can understand what is in store for us as we continue that struggle today. We should realize, even if we can’t create utopia, we can make things better. What is established by love, even if it is resisted by the world, will still bring about positive change and many people will be positively impacted by that change. Even if we seem to believe our life is one of failure, love will always make a difference, proving it is not a failure. Thus, we can see in a way which Abdul Ghaffar Khan could not that he was not unsuccessful. He was not a failure. He did start a movement of reform, one which has touched the lives of many and made them better, one which can be seen to continue to this day with present day reformers like Malala Yousafzai.

The translation done by Imtiaz Ahmad Sahibzada is, in general, excellent, however, he does often leave many words/notions, like jaloo (procession) or jalsa (public meeting) left untranslated, requiring the reader to constantly refer to the glossary at the end of the book. It is understandable why he does this, because all translation loses something of the thought and spirit of the original, but it would have been useful for some words to be translated in parenthesis after they are used. This, combined with the constant mention of people and events the reader might not be familiar with, does make the book sometimes a difficult one to read, but on the other hand, it also makes sure the reader pays careful attention to what they read, perhaps slowing them down so that they get the most of out of their reading experience. This is not a book to be read fast. It is a book to read slowly, so that upon reading it, the reader can properly ponder what they have read, learn from it, and use it to inspire them to change their lives and work, like Badshah Khan, for the betterment of humanity.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.