I recently read about the development of tourism in India since independence in 1947, and thought I’d look up how “ancient tourists” saw India.

The most well-known traveler is probably Megasthenes, a Greek who arrived in India in the fourth century BC, as an emissary to Chandragupta maurya’s court, from his neighbor Selucius Nicator. Chandragupta Maurya, who had supplanted the Nandas in Magadha, was the leader of a new national movement. He not only made himself master of northern India and forced Seleucus Nicator to surrender (c. 305 B.C.) the provinces of Kabul, Herat, Kandahar and Baluchistan, but possibly extended his empire to the south. His grandson Asoka ruled over an empire which stretched from the river Kabul to the river Brahmaputra and from Srinagar to Srirangapatnam. Chandragupta Maurya and his advisers, of whom Chanakya was possibly one, not only drew upon Brahmanical political concepts and institutions but also Greek and Persian administrative ideas, which they altered to suit local needs. All these aspects were recorded in great detail in Megasthenes Indica, in which he describes his appreciation for many aspects of the land.

Also among the most well-known are probably the Chinese Buddhist pilgrims. The greatest of the Chinese traveller-pilgrims was Hiuen-Tsang, who visited various parts of India between 629 and 645 A.D. At that time, Harsha was the chief potentate in north India and Pulakesin II Chalukya was the most powerful king of the South. Harsha was known for his scholarship, patronage of learning, philanthropy and toleration, though he himself was inclined towards Buddhism. Pulakesin II was superior to Harsha in military ability. His fame reached Khusran, King of Persia, leading to an exchange of gifts and embassies.

News of traveler pilgrims fades away after this point, as Buddhism itself began to fade in India. Because from the middle of the 7th century, i.e., roughly the time of the passing of Harsha and Pulakesin, there was no central power for nearly 100 years in the North or the South and, except for the powerful house of Kashmir, there was no leading dynasty. So there was consequently no patronage for writers and recorders of history, nor was there any scope for travelers to enjoy safe passage through the vastness of India.

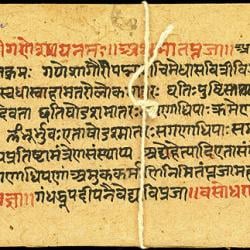

Education was also a big pull for travelers to India. Of India, “There is no country”, says Professor F. W. Thomas, where the love of learning has so early an origin or has exercised so lasting and powerful an influence”. In ancient India education was fostered by the State and its influence was widespread. There existed a network of educational institutions, hermitage schools, monasteries, guild schools, academies and Universities. The Universities of Takshashila, Nalanda, Kanchi, Mathura, Vikramasila, Odanta-puri, Nadia and Kashi were famous seats of learning.

These universities were famous throughout the ancient world, a stark contrast to today’s situation of education in India. The Western system of education was only introduced in India by the British. Their immediate aim in the early 19th century, when education through the medium of English began to spread, was to create a class of lower administrative personnel and destroy India’s cultural roots. Such education continued to be confined to the towns. There was no higher education in the Indian languages and even primary education was neglected. At no time during the British regime did literacy exceed 15 per cent. Facilities for technical and vocational education and research were also extremely limited.

India has always been a destination of choice throughout history. It is only since the coming of the British that this has changed. Hopefully, the government’s “Incredible India” and other initiatives will change this.