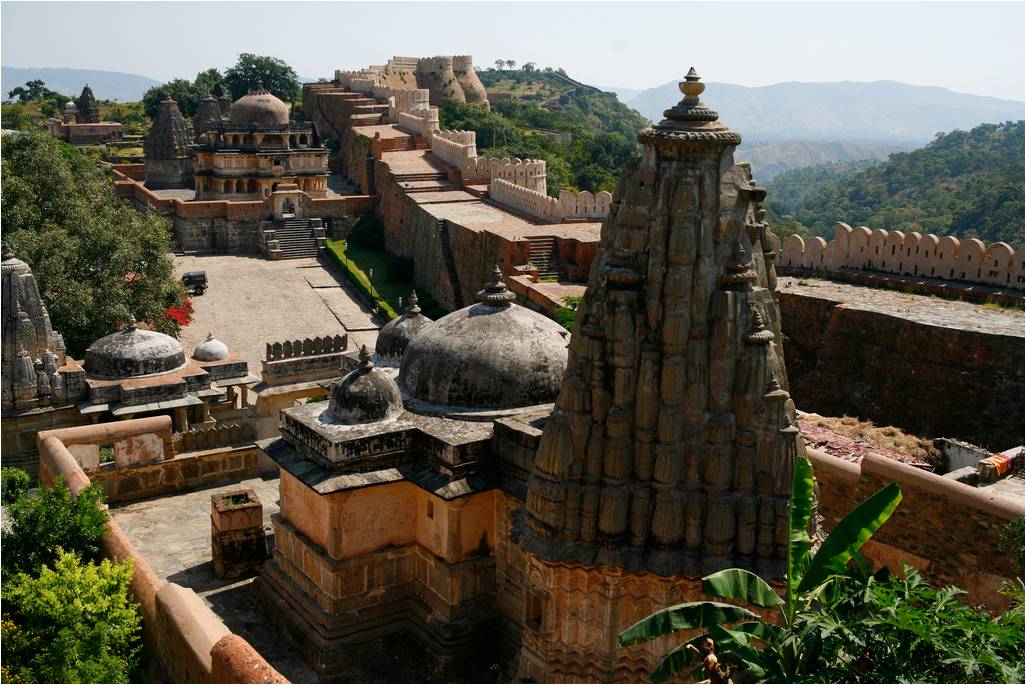

India’s textiles are intimately linked to its culture and Gods. For example, in Tamil Nadu, it was quite a common feature in the past for weavers to function out of temples. In fact, many of the weavers biggest “customers” were temples, which clothed deities in special cloth. This article is a brief look at some of the fabrics that have developed in Tamil Nadu’s temple towns, and how they are faring today.

According to the Institute of Indo European Studies, between the 16th to 18th Century, there were 280 varieties of textiles in Tamil Nadu. Most of them were exported from the ports of the Coromandel Coast. Europe, Africa and East Asia were the destinations.

The last comprehensive handloom census was in 2009, when there were 154,509 handlooms in Tamil Nadu, and 2.3 million in India totally. Most are family-based.

As of 2017, Tamil Nadu had 752 industrial-scale textile mills (handloom + machine), the highest number in the country. This is over half of the total 1399 textile mills in India.

In 2017, 232 textile mills were shut in Tamil Nadu, the highest in the country.

Tamil Nadu accounts for less than 2% of the country’s total raw cotton production, but has almost half of cotton spinning capacity in the country.

A Few Handlooms of Tamil Nadu

Kanjeevaram silk is one of the most famous handlooms in Tamil Nadu.

However, there are also the Chettinad, Chinnalapattu and Koorainadu, less well-known but still very fine cotton weaves. They do not receive the same hype as the Kanjeevaram.

Despite their fine quality, these weaves are dying as not many take to the family trade of making the sarees. The Koorainadu, for instance, handwoven for generations in Mayiladuthurai in Nagapattinam, now has only 10 weavers left. Poverty had pushed some of these weavers to abandon their craft and sell newspapers.

Even with the famous Kanchi cottons, weavers are losing their skills and the traditional Kanchi style has been lost in some ways. Earlier the distinctive borders of the old Kanchi cottons were made by children sitting on the other end of the loom pit opposite their parents. Since implementation of child labour laws, the sarees now have a single border. Such is the lack of traditional skill that weavers have to be being trained in the korvai technique which is a method unique to these sarees to interlock the border with the body.

The Madurai Sungudi, an erstwhile fabric of the royalty is suffering due to several cheap imitations in the market now.

Woraiyur in Tiruchi was once famous for its handloom saris. It was popular among the Indian diaspora in Singapore, Malaysia and Sri Lanka. Today, this weaving tradition is on the threshold of extinction.

According to a weaver, there were 500 to 600 handlooms in Tiruchi in the early 1990s. The number started dwindling gradually after the introduction of powerlooms in various parts of the country including Coimbatore, Tirupur and Erode. It was 150 handlooms until five years ago. Now, it is just 30.

An official at the office of Assistant Director of Handlooms says that only around 100 weavers are active now. Of them, 90 are receiving old age pension.

Mahatma Gandhi said “the spinning wheel is a nation’s second lung”. He considered the spinning wheel a symbol of revolution

Famous Tamil Saying: “Ulavum nesavum kann enath thagum” which means “Agriculture and weaving are like two eyes.” Hopefully the new government of India will take note and do something for the struggling handloom sector.