The Dalai Lama is so well-known that he seems as if he belongs to the entire world. But on my visit to Tibetan Buddhist sites in Bloomington, Indiana, I realized that he also belongs to a family–one with surprisingly deep roots in the U.S.

Born Tenzin Gyatso, the Dalai Lama began his monastic education at the age of six. But that didn’t mean that his biological family ties were severed. Throughout his life he has continued to keep in touch with his relatives, including a branch that lives in Bloomington (now there’s a surprising turn of the karmic wheel).

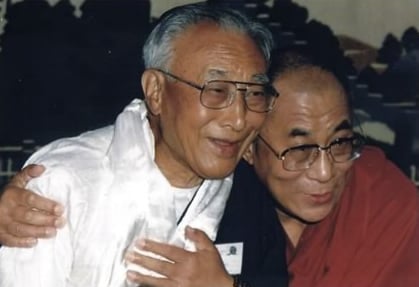

The eldest brother of the Dalai Lama, Thubten Jigme Norbu, escaped Tibet in 1950 and, after being granted political asylum by President Harry Truman, became a professor of Tibetan Studies at Indiana University. Though he had been a high lama in Tibet, when he left his homeland he gave up his monastic vows and later married. Throughout his life he was a passionate advocate for his nation, helping to publicize human rights abuses in Tibet, campaigning for Tibetan independence, and educating students about his native culture and religious traditions. In 1979 he established what is now the Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center (more about that center in my next post). In his later years, he walked more than 8,000 miles on peace walks to promote awareness of the atrocities in Tibet and the cause of Tibetan independence.

When I visited Bloomington I was honored to meet Norbu’s widow Kunyan, his son Kunga, and his daughter-in-law Ya Ling. Over a delicious meal of Tibetan food prepared by Kunyan and Ya Ling, our group got the chance to visit with a family that straddles American and Tibetan cultures with remarkable grace and good humor.

Kunyan Norbu is one of those people who radiates warmth. After five minutes, I wanted to ask her if she would be my grandmother. Though she is without pretense, she comes from a noble and ancient family in Tibet. “I can trace my lineage back 50 generations,” she told us (let me do the math for you–that’s about 1,000 years).

As we ate, Kunyan told us of meeting Norbu, coming to the U.S., and raising three sons in Bloomington. For years she helped her son Jigme and his wife Ya Ling operate the Snow Lion Restaurant in the city. Left a widow by Norbu’s death in 2008,, she now divides her time between Seattle and Bloomington.

The saddest part of her story came when she told of the death of her son Jigme in 2001. Like his father, he had been a tireless campaigner for the cause of Tibetan independence. While on a walk in Florida to raise awareness for that cause, he was killed by a car.

“It should have been me who died,” Kunyan told us, her voice raw with grief. “But we are trying to carry on his message of peace.”

She said that the situation in Tibet today upsets her so much that she tries not to read too many details about what is going on. She spoke of being reunited with her sister after many years and learning that she had been tortured. “Out of a population of six million Tibetans, two million have died,” she said. “Here we can speak and say whatever we want. There, they cannot speak. So we have an obligation to speak for them.”

I was surprised to learn that Jigme’s widow, Ya Ling, is Taiwanese-Chinese. But Ya Ling told us that the Tibetans do not hate the Chinese people, for they realize that it is their government that deserves the blame, not ordinary citizens. Ya Ling is carrying on her husband’s legacy in Bloomington, both by running a scaled-back version of their original restaurant (see below) and by helping to raise awareness of the situation in Tibet through fund-raisers and educational efforts.

When asked how the Tibetan people have been able to survive in the face of such oppression, Kunyan said that Tibetans are an extremely strong people: “We are hard workers, we are curious to learn new things, and we are adaptable.” Surely the Norbu family exhibits all of those traits.

On a more personal level, Kunyan also spoke about what it was like to be the sister-in-law of the Dalai Lama. He is her spiritual leader as well as a family member, she said, and when she is around him she finds it difficult to look in his eyes. Then she added, somewhat impishly, “But they are a fun family. My husband and his brother would laugh a lot when they were together.”

Her most touching story was of the last time her husband met his brother. Norbu had been incapacitated by strokes and she had to take him in a wheelchair to their meeting. “When His Holiness saw us coming, he came quickly to us, knelt in front of my husband’s wheelchair, and put his forehead against his,” she recalls. “They remained like that for a long, long time. My husband was not able to speak because of his illness, but I think they were talking to each other without words. When they separated, both of them were crying.”

I feel incredibly fortunate to have been introduced to this family and to have a window into a more personal side of his Holiness the Dalai Lama. All of us, in the end, are products of our family, even someone with such an unusual life as the Dalai Lama. There’s something very endearing about that image of Norbu and his brother, foreheads pressed together. Both men had traveled far and endured much, but in the end, the tie of brotherhood remained strong between them.

If you happen to find yourself in Bloomington, you can enjoy Tibetan food at Ya Ling Norbu’s restaurant, the Snow Lion Express, at 506 West 4th street Bloomington.