Today’s post is by guest blogger Bob Sessions:

Today’s post is by guest blogger Bob Sessions:

Before Lori and I saw the Dalai Lama, we had the privilege of attending part of Louisville’s 18th annual Festival of Faiths (because we were also attending a meeting of the Midwest Travel Writers Association, we dubbed the week our Bourbon and Buddhism Tour). While I enjoyed many parts of the week, to me the highlight was the chance to hear the brilliant, spiritually advanced speakers at the Festival of Faiths.

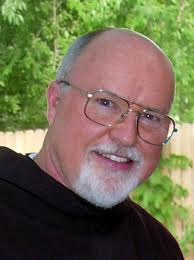

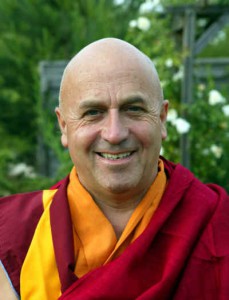

This year’s theme was Sacred Silence: Pathway to Compassion. Religious teachers from many traditions told stories and offered insights from their practices, dialoguing with each other in ways that revealed deep similarities as well as differences. (You can view the presentations yourself at the Festival of Faiths YouTube) I was especially delighted to meet two of my heroes, Franciscan priest and author Richard Rohr and Buddhist monk and scientist Matthieu Ricard.

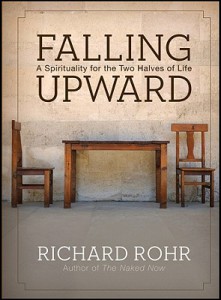

As I’ve written on this blog in the past, I’ve been very taken with Richard Rohr’s work (especially Falling Upward, but also Immortal Diamond

and The Naked Now

), and I am presently taking an eight-week online course through his Center for Action and Contemplation. Rohr didn’t disappoint me or the large crowd that gathered to hear him talk about silence and contemplation.

Rohr’s thesis was simple, but its implications are profound. He likened silence to the great spaces that provide the infrastructure of the universe: Without spaces between objects or within atoms we would not have a universe; without silence we would not have communication nor reap the benefits of compassion.

Rohr said this: Silence is what surrounds everything. It is the space between letters, words, and paragraphs that makes them decipherable and meaningful. When you can train yourself to reverence the silence around things, you first begin to see things in themselves. This “divine” silence is before, after, and between all events for those who see respectfully (to re-spect is “to see again”).

We all have experienced the miscommunication that can result from a too-hasty response to an electronic or spoken message, and even when we try to be temperate in our responses, we often fail to respond compassionately. My studies of Native American societies have introduced me to much more effective rituals of silence and communication, such as a “talking stick” that prevents multiple people from speaking at once, or the patient respect given to those who take time to think before speaking (something that we rarely practice in our society, unfortunately).

One of Rohr’s major ideas is that we misunderstand the sacred/profane distinction. He contends that no particular place, event, person, or thing is sacred while others are profane. (Peter Mayer’s wonderful song Everything is Holy Now expresses this concept beautifully) Instead, everything can be sacred or profane, depending on how we approach it. If we only scratch the surface of something we are dwelling at a profane level; if instead we spend time with it in silence we can move to the sacred hidden within. Deep communication is embedded in silence.

According not only to Rohr, but to every other presenter at the festival, our main obstacle to this deeper communication and communion is the cacophony of noise in our heads and our ego-driven desires to control and win. Contemplation, which can take many forms, helps us diminish this interior noise.

This point was amplified in a session on the “science of compassion” with Matthieu Ricard and Stanford neuroscientist James Doty. The two have been pioneers in mapping what happens in people’s brains when they meditate. Not only are meditators’ brains significantly altered while meditating, but such practices bring them improved health, longer life, and better human relations even after they complete their practice. They have diminished the internal dialogue of the ego, allowing them to listen more attentively and accurately to what is in the moment.

Have you ever noticed how poor most of us are at listening to others? Few people ask genuine questions about others’ lives and listen, without judgment, to what is said. You don’t have to be a therapist to realize that contained within most messages are layers of emotion, history, hurt, fears, joys and sorrows, and one important path to deeper understanding and communion with the sacred is to listen in silence.

The ultimate goal of spiritual practice is to reach “unity consciousness,” to experience the connectivity we have with all that is. Thomas Merton, whose story is intertwined with the Dalai Lama’s visit to Louisville, broke through to this level on a street corner in Louisville in 1958 (see A Thomas Merton Tour). He suddenly had the realization that he was interconnected with everyone around him and that each person was holy. The Buddhists call this fundamental interconnectivity “dependent origination.” Years of meditation and prayer ushered in Merton’s revelation and it can do the same for us.

One final thought about the Festival of Faiths: it taught me how important it can be to be in the presence of someone we admire, especially when it comes to spiritual matters. It’s one thing to read a book, and it’s another to listen to their words in person. I was somewhat surprised to find both Rohr and Ricard very approachable. I didn’t feel intimidated talking with them and they did not parade their intelligence as I’ve often seen in academic gatherings. Their extraordinariness lies instead in their highly honed capacities to greet each person as a fellow traveler and to listen to their stories. More than their clear and powerful ideas, such character traits communicate what a rich spiritual life offers—serenity, joy and compassion.