You might say that the topic of death is hot these days. Many people are questioning the standard Western practices surrounding death, which too often occurs after medical interventions that prolong suffering, prohibit people from coming to a sense of peace about their dying, and separate people from their loved ones when they need them the most.

That’s why I think Kathleen Dowling Singh’s The Grace in Dying : How We Are Transformed Spiritually as We Die is so important. Regular readers may remember that not long ago I raved about Singh’s book The Grace in Aging: Awaken as You Grow Older

. Both books are remarkably wise, but I think The Grace in Dying is even more profound in its insights. It came out a number of years ago, but its truths are timeless.

Losing a loved one–or facing the end of one’s own life–is almost always a wrenching, painful experience. Singh does not deny or gloss over this reality. But her book draws on many spiritual traditions, as well as the insights of transpersonal psychology, to assert that dying is more than a tragedy: it is the path of spiritual transformation.

In the late 1960s, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross helped ignite interest in the dying process with her theory that those who are dying commonly go through the stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Singh believes that these stages are only part of the profound changes that occur as people confront their mortality and enter into the mystery of death. She writes of the levels of awareness and being that transcend our personal consciousness. Dying, she writes, is a process of natural enlightenment, a journey that leads us back to the Ground of Being (or God, or Jesus, or however one describes Spirit) from which we once emerged.

Singh has been at the bedside of hundreds of dying people. She draws on her own experiences, her Buddhist training and practice, and her observations of the dying process to weave a powerful testimony to what she calls the Nearing Death Experience.

Singh has been at the bedside of hundreds of dying people. She draws on her own experiences, her Buddhist training and practice, and her observations of the dying process to weave a powerful testimony to what she calls the Nearing Death Experience.

Singh believes that the Nearing Death Experience is similar to its better-known counterpart, the Near-Death experience, but with some key differences. She writes:

“The two processes have many similarities, although the experience of nearing death through terminal illness is slower and more protracted [than the typically sudden injuries that trigger a Near-Death Experience]. I believe, from hundreds of pieces of anecdotal evidence, that in the dying process a person makes many partial, preparatory trips into dimensions of being beyond our normal consciousness, experience, and identity. The Nearing Death Experience finds a human being flickering back and forth between realms of existence or states of consciousness, almost like a diver practicing the approach to a dive: he or she jumps into the air, then returns to the familiarity of the board, jumps and returns, jumps and returns until he or she makes the final ascent to the dive.”

Singh’s most important message is one of comfort. She says that many spiritual traditions, while different in details, assert that one’s death is not something to be feared. “Like others who participate in this awesome process of dying, I see ordinary people like you and me die in peace and in serenity, without a struggle, dissolving out of their bodies,” she writes. “They die into their True and Essential nature. They appear, often knowingly, to melt into Spirit, as naturally as a snowflake melts on the hand.”

Singh says this about what she calls the via negativa of dying: “The defining elements of suffering, the removal of unreality, of the inessential, and the creation of new levels of consciousness and identity are present [in the dying process.] The experience of living with terminal illness is an experience of subtracting daily. Each day, a new factor is eliminated from who it was the person thought he or she was. It is a shedding of illusory identifications or definitions of self.”

Loved ones may naturally see this as a tragedy (and indeed, for those who are left behind, death can be a terrible loss, particularly when someone dies prematurely). But for the person who is dying, this process is one of spiritual rebirth and transformation. “No more energy goes into hiding and maintaining the dreadful secret that we are ordinary human beings, just like everyone else,” she says.

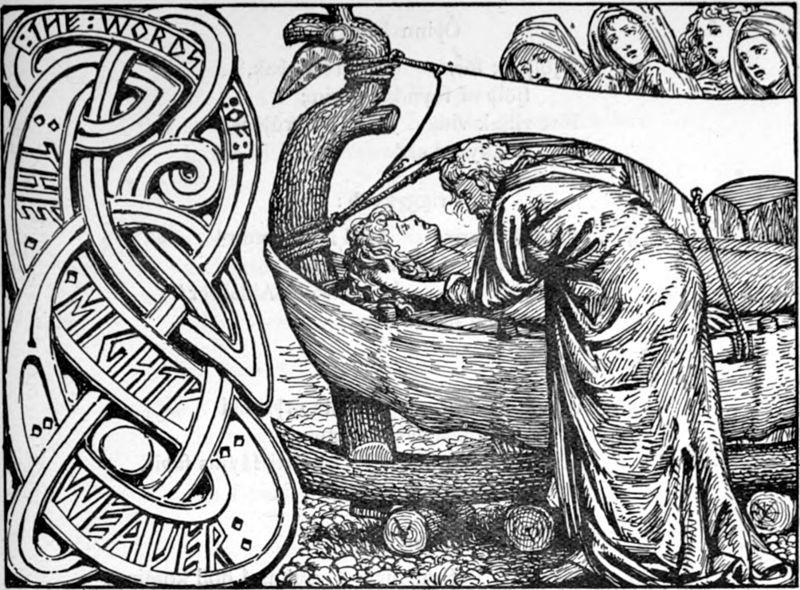

Singh offers a traditional Buddhist image to suggest what the experience of death is like: Imagine an empty vase in which the space inside is exactly the same as the space outside. Only the fragile walls of the vase separate one from the other. Our buddha mind is enclosed within the walls of our ordinary mind. When we die, it is as if the vase shatters in pieces. The space “inside” merges into the space “outside.” They become one. There and then we realize that they were never separate or different. Buddhists would say this is the return to the Ground of Being; in Christian terms, we become enfolded in the arms of God. All words are merely fingers pointing at the moon of this truth, but Singh does as good a job as any author I’ve ever read of exploring the spiritual transformation of the dying process.

The Grace in Dying is a book to savor slowly, allowing its wisdom to sink deeply into one’s heart.