One of the religious groups I’ve always admired are the Mennonites. Though small in number, they have an influence far greater than their size would suggest. After a natural disaster, for example, they are often the first to arrive to help and the last to leave. Along with the Quakers, they are one of the historic peace churches, with a long tradition of pacifism and non-violent resistance. These good folks do much to improve the reputation of Christianity.

So on a recent trip to Kansas, I was happy to visit the Kauffman Museum, one of the largest Mennonite museums in the U.S. It’s affiliated with Bethel College, a Mennonite liberal arts school in North Newton, Kansas. At the museum I learned why south central Kansas has the largest Mennonite population west of the Mississippi River. During the 19th century, railway companies were looking for groups of people to buy lots along the tracks being laid across the continent. They sent German-speaking representatives to Europe, where they traveled to isolated Mennonite communities to try to entice them to the U.S.

Many Mennonites at the time were worried about the rise of nationalism, especially in Russia, and they were lured as well by the promise of good, reasonably priced farmland in a country with far greater religious tolerance. About 18,000 Mennonites came to the Great Plains between 1874 and 1884. Often whole congregations would move together, creating communities and churches in their new home.

The Kauffman Museum’s exhibits describe the experiences of these people as they established themselves in the U.S.. Its grounds include a 19th-century farmstead and a tallgrass prairie that shows what the landscape looked like when the Mennonites arrived.

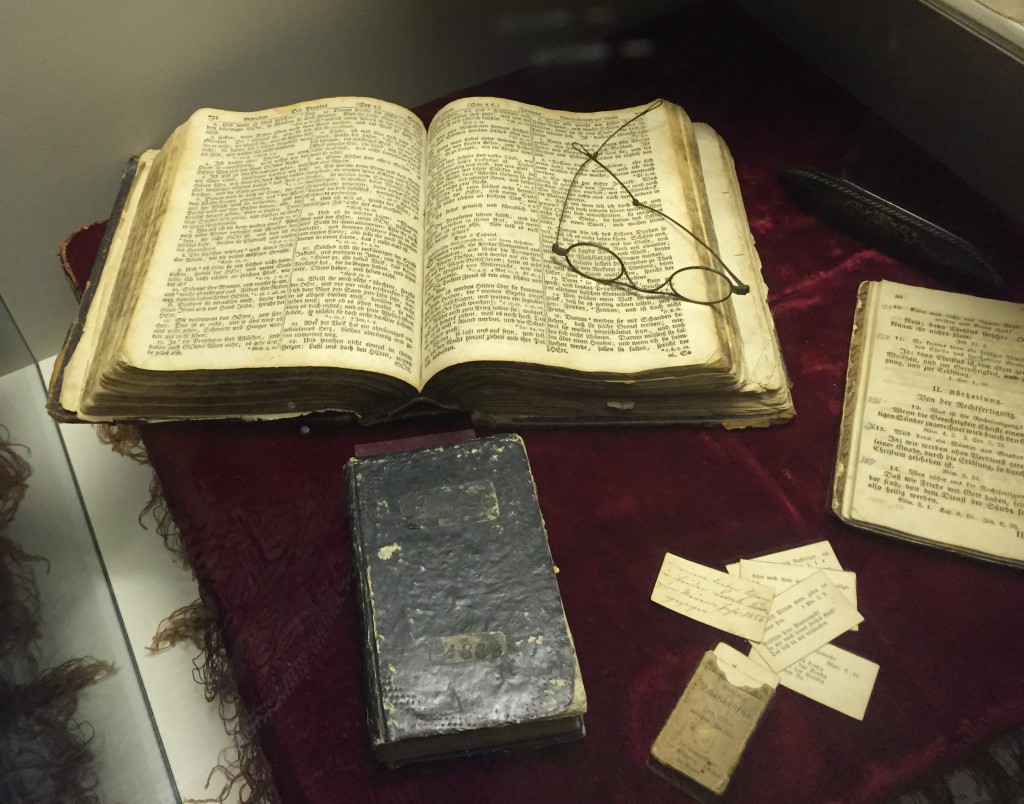

While I learned a lot from the historical information at the Kauffman Museum, I was most intrigued by its display on martyrdom. This denomination was often persecuted in Europe because their members refused to serve in the military and because of their practice of adult baptism. (Killing people over baptism? Honestly, with these skeletons hanging in the family closet, sometimes I’m embarrassed to be a Christian.) One of the Mennonite’s most important books became Mirror of the Martyrs, a 17th-century volume that recounts stories of people who died for their faith without retaliating against their oppressors.

This exhibit’s power comes from the ways in which it connects stories of the past to today. One area, for example, poses a series of provocative questions:

“Why do good people torture and kill?”

“What beliefs are worth dying for?

“Why do the powerful fear the weak?”

“Who are the martyrs today?”

These questions are especially poignant, of course, given the news that we hear nearly every day, from the recent shootings at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina to the stories of the victims of ISIS in the Middle East. The Mennonites have been pondering these questions for a long time. The exhibit was interesting in that it didn’t give pat answers to these hard questions, but instead detailed stories of personal bravery and quiet fortitude despite terrible oppression. This 16th-century quotation highlighted in the display sums up their response to injustice: “Martyrdom is never an affair of weakness, but rather strength. Only a hero is able to walk the path of martyrdom.”

Which brings me to the other Kansas landmark I want to tell you about—the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home. You wouldn’t think there would be much in common between these two sites, would you? But bear with me, for there are more connections that you realize.

Eisenhower grew up in Abilene as the third of seven sons in a family which was part of the River Brethren, a denomination closely related to the Mennonites. His mother in particular was a devout believer who tried to instill in her sons a commitment to the faith.

Dwight was a good student who wanted to go to college despite his family’s limited means, and so he applied to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, which has free tuition for its students. Our guide at the museum told us that when Dwight left for college, it was the only time his mother ever cried in public, because she was so upset he was going to a military academy.

You know the rest of the story. Dwight Eisenhower went on to become one of the most important military leaders in history. During World War II he was Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe. He was responsible for the planning and execution of the D-Day Invasion, the largest military invasion ever staged. After the war ended, he was elected President, a position that also required him to send men to combat. Eisenhower was an honorable, good man, but think of all the ways in which he wandered far from his family’s pacifist beliefs.

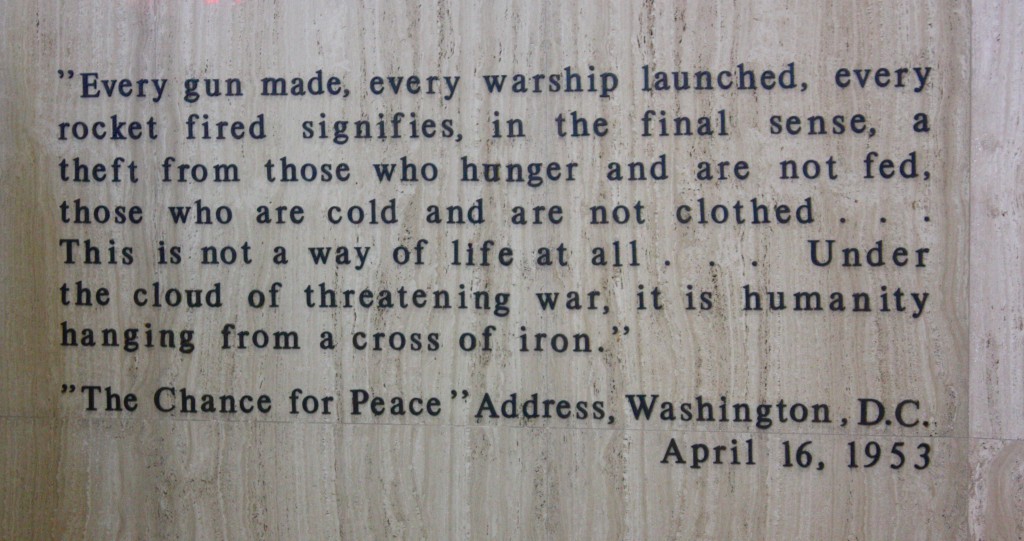

Except maybe not so far after all. For at his grave in a chapel on the grounds of the museum, there are several quotes, each carefully chosen to distill the essence of his life of service and leadership. The one that brought tears to my eyes is a passage taken from one of his speeches, words that make me think that even after all the killing he had seen and participated in, the voice of his mother still whispered in his ear. The words are taken from a speech he gave in 1953: