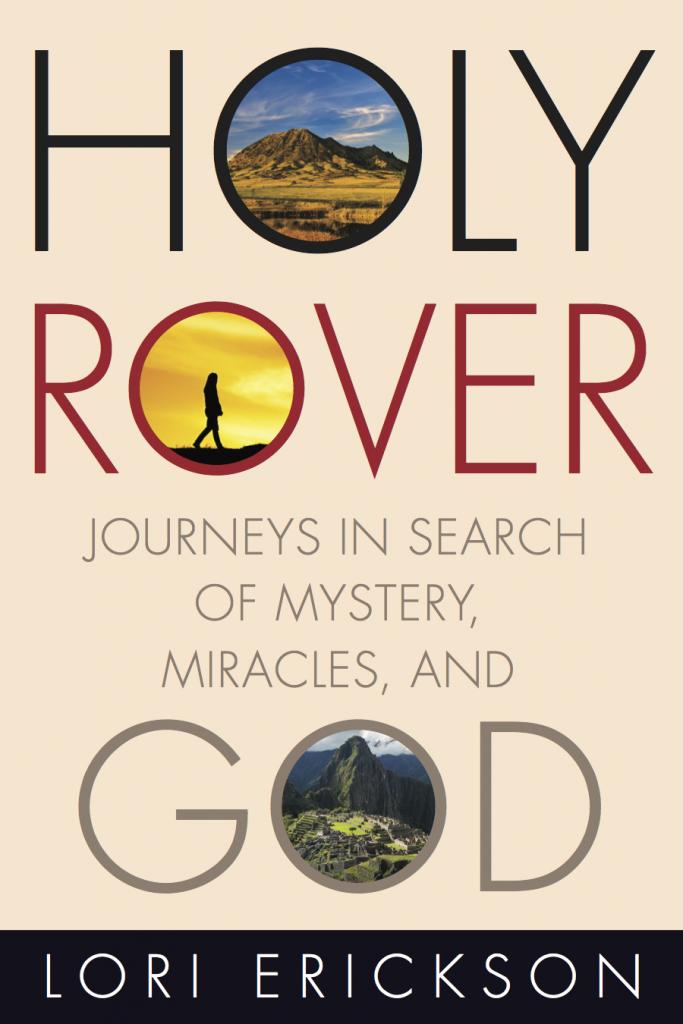

Ta da! That book I’ve been telling you about is finally released. You can now buy Holy Rover: Journeys in Search of Mystery, Miracles, & God as a hardcover, audiobook, or e-book. Or ask your library to order a copy (or 2 or 3 or even 20—it’s a good choice for book clubs!).

Holy Rover is a memoir structured around trips to a dozen holy sites around the world. Here, in honor of its debut, is an excerpt, slightly adapted from the original:

I’m sitting on the top deck of a boat docked on the bank of the Nile. Earlier in the day I’d toured its ancient temples in brilliant sun and fierce heat, but the evening brought air that was blessedly cooler, as soft as a pashmina shawl against my skin. A full moon hangs above the city, illuminating the outlines of dust-colored buildings. As stars multiply in the velvet sky above, I savor the scene below me, one that has changed little in thousands of years.

And I find myself wondering: how did an Iowa farmer’s daughter get here?

The reason is that I fell in love with pilgrimages, the sacred journeys that can begin in any corner of the world and eventually lead to Jerusalem, or Lourdes, or Machu Picchu, or to a boat docked on the bank of the Nile.

My passion for pilgrimage springs from a fascination with religion in all its many weird and wonderful permutations. What makes some people handle snakes and others fast for Lent? How do Mormons get young people to devote two years of their lives to knocking on the doors of strangers? What’s it like to go to Mecca? Why do Orthodox churches have those slightly scary looking icons? Do Trappist monks ever burst out laughing in the middle of the Great Silence? Do many people really believe that pieces of the True Cross exist? Why do people crawl on their knees to the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City? What do nuns wear under their habits and Buddhist monks under their robes? All of it, the big and little questions, intrigue me.

In my search for the holy, I’ve wandered down many paths. I’ve been a Lutheran, a Wiccan, a Unitarian Universalist, a Buddhist, an Episcopalian, and an admirer of Native American traditions. I’ve been spiritual-but-not-religious and religious-but-not-spiritual. I can read tarot cards and balance chakras. My spirit animal is a bear, which is a great relief because for years I thought it was a raccoon, an animal that while perfectly fine lacks a certain gravitas.

After many years of spiritual wandering, I’m now a committed Christian, but one who frequently flirts with other religious traditions. I like to think I’m in an open marriage with Jesus—we’re both free to spend time with other faiths, but at the end of the day we always come home to one another.

Through it all, the spiritual practice that’s most shaped me is pilgrimage. My journeys have given me essential keys to understanding what was happening in my inner life. They’ve challenged my assumptions, forced me to confront my fears and prejudices, and deepened my faith. Among other changes, they eventually led me to become a writer specializing in spiritual travels and to ordination as a deacon in the Episcopal Church.

I hope when people read about my pilgrimages, they’ll be inspired to make their own, whether they’re Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, or someone who kinda-sorta thinks there might be something more to ordinary reality than is immediately obvious.

A warning: once you set out on trips to holy places, if you’re paying attention at all, your life will change.

***************************

I can pinpoint the exact moment my interest in writing about spiritual travel was born. I was browsing a magazine, one full of ads for cruises and articles on Five Perfect Days in Tahiti. But near the back I read an article of a different sort: it was about staying in retreat centers, primarily monasteries, across the U.S.

The article was a revelation. I hadn’t even known that I could stay in a monastery, unless, you know, I was thinking of joining one. But it turns out that such places welcome visitors, and that the retreat business is booming for many of them. While the number of nuns and monks is going down, the number of people who want to experience the serenity of these communities is going up. The article reported that such places are often booked months in advance.

I looked up from my reading and said to myself, “That’s what I want to write about.”

So began my career as a travel writer specializing in holy sites. While I do other bread-and-butter writing projects that help pay the bills, much of my time is devoted to writing about the many places in the world where people can experience the holy—a fulfilling blend of my long-standing interest in spirituality and my passion for travel.

Essentially what I write about is pilgrimage, which is one of those pious words that scares some people off because they’re afraid they’re going to have to walk over rocks in bare feet and eat hardtack for six months. It’s actually less esoteric than that. Most travelers have already been on a pilgrimage once or twice in their lives, whether they know it or not— when they visited the town where they grew up and walked its streets with a full heart, for example, seeing everything through the lens of memory. Or when they took a trip with a friend facing something big and scary, like a serious cancer diagnosis, and along with the fun was the knowledge of a powerful undertow just beneath the surface, making every stop for ice cream and view of a sunset bittersweet.

Such trips are pilgrimages because they touch the heart and soul. There’s nothing wrong with an ordinary vacation; sometimes what we need most is a beach, a mystery novel, and a gin and tonic. But at other times—which tend to come after losses and at transition points like graduations, decade birthdays, and retirements—the road calls to us in a different way. Even if we think we’re not religious, even if we’re skeptical of any kind of spirituality, something in our DNA draws us to wayfaring. I suspect it’s part of what first drew our ancestors out of the trees on the savannas of Africa and eventually to every corner of the earth.

The sacred enters our lives through the tiniest of openings, often slipping in underneath a door that slams shut: the job ends, the lover leaves, the friendship dissolves into bitterness. Or the call may come through the comment of a stranger at a bus stop or in a headline we happen to read at a checkout counter. We tell ourselves we’re foolish for listening to that inner urging, and yet we pack our bags and set out.

Pilgrimage is a nearly universal practice in religion, with Muslims journeying to Mecca and Jews to the Western Wall in Jerusalem while Christians walk in the footsteps of Jesus and the saints. Hindus travel to the Kumbh Mela, a festival said to be the world’s largest religious gathering, while Buddhists go to Bodh Gaya in India where the Buddha attained enlightenment.

Whether a seeker sets out alone on a deserted trail or travels in the company of like-minded souls, pilgrimage is both an outer and inner journey. Ordinary trips bring a change in scenery; pilgrimages are meant to trigger a change of heart.

Especially in the pre-modern world, a pilgrim had to be a little crazy even to consider setting out from home. Because travelling was so treacherous, pilgrims would put their affairs in order before they left: they would pay outstanding debts, write their wills, and make provisions for dependents. In the Middle Ages, it was traditional that Christian pilgrims would be blessed by a priest and anointed with holy water. If they died on the trip, they’d be ready to meet their maker, having squared both earthly and spiritual accounts.

The rigors and dangers of pilgrimage included robbers, rivers that had to be crossed on tipsy ferries, high mountain passes battered by winds and snow storms, ship passages plagued by seasickness and shipwrecks, and overnights in inns that were riddled with vermin, lice, and bedbugs. Anyone who’s ever complained about hotel accommodations on a package tour should contemplate what it was like to travel for most of human history.

The rigors and dangers of pilgrimage included robbers, rivers that had to be crossed on tipsy ferries, high mountain passes battered by winds and snow storms, ship passages plagued by seasickness and shipwrecks, and overnights in inns that were riddled with vermin, lice, and bedbugs. Anyone who’s ever complained about hotel accommodations on a package tour should contemplate what it was like to travel for most of human history.

Such trips were sometimes undertaken as a form of penance (forgive me, Lord, for sleeping with my brother-in-law) or to fulfill a promise made to God after the fulfillment of a prayer (thanks so much for my recovery from smallpox). If pilgrims suffered some along the way, all the better, for the experience likely made them realize their dependence upon divine providence. We should never forget that travel and travail share the same root.

The popularity of pilgrimage has waxed and waned through the centuries, flourishing during the Middle Ages and declining during the Reformation and the Age of Enlightenment. But even at its lowest point, it never disappeared completely, and today we may be entering a new era of pilgrimage, despite (or perhaps because of) the growing disillusionment with organized religion. Especially in Christianity, people are finding on the road what they cannot find in churches.

And one of the truths of pilgrimage is this: often its most important part is not the destination, but what happens on the way.

Excerpted from Holy Rover: Journeys in Search of Mystery, Miracles, and God

Stay in touch! Like Holy Rover on Facebook: