Striking, isn’t it?

And maybe a bit unsettling?

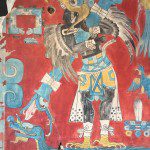

I came upon this figure at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Bob and I and our friend Brian spent several days in Mexico City before starting our Maya Temples of Transformation tour with Sacred Earth Journeys. Our time at this museum—one of the world’s greatest—gave us an invaluable background for what we would later see on our Maya trip.

Of all the marvels we saw at the museum, the figure pictured above most intrigued me. The jade mask and jewelry were found on the body of a Mayan leader named Pakal, who ruled the city-state of Palenque for almost 70 years in the seventh century. Every part of his elaborate burial finery had symbolic significance, from the number of strands in his necklace to those peculiar ear pieces that jut out from his head. Note, too, that the mask has crossed eyes, which were considered beautiful in Mayan culture.

I stood transfixed by this mask for quite some time, though I wasn’t sure why. Maybe it was the sheer weirdness of it, as well as the beauty of its craftsmanship. There was a haunting quality about it as well, something that seemed to speak in words I couldn’t understand about a culture very different from my own.

A few days later, I stood in front of Palenque’s Temple of Inscriptions, the place where this mask was found.

Located in the Mexican state of Chiapas, Palenque was founded around the year 100 BCE. It reached its height between 600-800 CE, and then declined in the early 10th century, for unknown reasons. Today it’s one of the most studied of all the Mayan sites. Though smaller in size than Chichen Itza or Tikal, it has exquisite architecture and carvings. Only a small fraction of Palenque has been excavated, but what’s there is marvelous indeed.

As at all Mayan sites, the temples here were likely built to align with astronomical phenomena. Working without telescopes, the Mayan nevertheless had an amazingly sophisticated knowledge of astronomy and mapped the movements of the stars and planets with great accuracy. They also kept multiple calendars geared to various celestial cycles and developed complex writing and mathematical notation systems.

As soon as I entered Palenque, the Temple of the Inscriptions immediately drew my gaze. It’s the largest of the many buildings at the site, with steps arranged in nine levels. Built during Pakal’s reign, it’s named after the hundreds of glyphs located on the temple walls at its top. Originally it was painted red, with its carvings detailed in bright colors. But even with its present appearance of weathered, gray limestone, it’s a exquisite building, perfectly proportioned, beautifully designed.

In 1952, Alberto Ruz Lhuillier made a remarkable discovery atop this temple: he uncovered the beginnings of a stairway that led down through the center of the structure. After four years of excavation, he at last came to Pakal’s tomb, one of the greatest treasures of pre-Columbian archeology. This is the New World equivalent of the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in Egypt.

And while the jade mask in the museum was stunning, I was even more amazed when I learned what covered Pakal’s sarcophagus (see below).

This massive lid of limestone, 12 x 7 feet in size, is covered with an intricate, carved design that people have been trying to interpret ever since it was discovered. The image shows a man either descending or ascending a World Tree, a symbol that has roots in the underworld, a trunk in this world, and its branches in paradise. The man is wearing garments similar to those of the Mayan Maize God, and surrounding him are sacred symbols of many kinds.

If this all looks vaguely familiar, it’s because you might have seen it on a late-night TV program on ancient aliens. The craze started with a 1968 book by Erich von Daniken called Chariots of the Gods. When he looked at this image, he saw a space man being propelled by a rocket ship, a theory that’s been giving anthropologists headaches ever since. “No! No! Don’t believe him!” they collectively say, pointing out that Mayan culture was perfectly capable of creating its many wonders all on its own without the help of overlords from the stars.

Thankfully, you don’t have to buy the ancient aliens thesis to appreciate this remarkable work of art (which we saw only in pictures, since you can’t get inside the tomb without special permission). But there is indeed something otherworldly about this image, which shows a spiritual transformation of some sort, a movement between realms.

Today Pakal’s body rests underneath the Temple of Inscriptions, while most of the items found in his tomb are safely ensconced in the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. I felt fortunate to have seen those treasures, because it made me fully experience what I experienced at Palenque.

On our tour of Palenque, I also greatly appreciated the fact that we were given time simply to be. Too often tours try to cover so much information and territory that you’re left exhausted. But if you’re going to truly experience a sacred site, you need some time to settle in. I was grateful to spend much of the afternoon wandering on my own amid the temples, climbing up steep steps to perch on platforms overlooking the green lushness of the surrounding jungle, drinking in the vistas.

Here’s a curious thing, one that I’m a little embarrassed to admit. Our group had arranged to meet back at the entrance gate late in the afternoon, and I stretched out my time at Palenque as long as I could. Nearing the departure time, I realized I needed to hurry.

A shortcut led through a dimly lit tunnel that we’d walked through before as a group, a passageway that wound through the ruins of the palace. I started to enter it, and then stopped.

The light had shifted from earlier in the day, and it seemed darker than I remembered. There were no people around, not even voices in the distance. And I realized that I was scared to go into the passageway. I didn’t fear other humans, but instead I wasn’t entirely sure that spirits weren’t hovering around. Something about the way the walls loomed high around me, perhaps. Or maybe it was just an over-active imagination. But I took the long way back to the entrance, even though it entailed much more walking.

I smile when I think back to that moment now, because it sums up to me the essence of Palenque. This is a place that exudes the Mysteries of the Maya. Palenque is both dead and alive. No one lives there, and yet perhaps they do.

Next post: Yachxilan, where I learn about Mayan ceremonies.

Stay in touch! Like Holy Rover on Facebook: