In Mexico City, I turned a corner in a museum and there he was: the God of Death, a six-foot-tall, skeletal figure standing with clawed hands outstretched, his face twisted into a grimace. Mictlantecuhtli, the Aztec god of the underworld, clearly wasn’t happy. And I wouldn’t be happy either if my liver was dangling outside of my body, as his was.

Standing before him, both repelled and fascinated, I recalled being at a Day of the Dead celebration in Chicago last fall. Mictlantecuhtli had been there, too, I now realized, a shadowy presence behind the faces painted with the pallor of death.

I’d come to Mexico to learn more about the traditions that underlie Dia de los Muertos, searching for insights from a culture that seems preternaturally comfortable with constant reminders of mortality. Even the shops at the Mexico City airport had Day of the Dead knickknacks (figurines that must add to the anxiety of those with a fear of flying). Skeletal figures wearing ball gowns and tuxedoes filled the shelves, looking like members of a raucous family who didn’t want to end their partying just because they’d stopped breathing.

The first stop on my Mexican tour was one of the world’s great museums: the National Museum of Anthropology, which covers 3,000 years of Mesoamerican history. In its central courtyard, a huge column carved with mythological and religious symbols supports an umbrella-like roof, while the surrounding buildings hold an astonishing array of artifacts from the dozens of cultures and civilizations that have shaped the region.

The color and drama of the history recounted here made my own Scandinavian heritage look pale and paltry (while I take pride in my feisty Viking genes, most of my heritage, alas, has more in common with an Ingmar Bergman film). The museum’s exhibits showed how two cultures in particular have influenced modern Mexico: the Aztec (also known as the Mexica) and the Maya, both of which had a somewhat exuberant relationship to death, to put it delicately.

The Aztecs, who ruled central Mexico for two centuries before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in 1519, get the prize for sheer bloody awfulness. They loved going into battle, and even in their peaceful moments practiced a number of grisly forms of human sacrifice, typically of prisoners they’d captured from neighboring regions.

The Aztec deities, unfortunately, were a particularly difficult and hard-to-please lot. They demanded blood in exchange for pretty much everything, from keeping the land fertile to making it rain. To appease them, the most common form of killing was to cut out the hearts of victims while they were still alive, a procedure performed by priests at the top of tall, pyramid-shaped temples. Once the heart was extracted and placed on a ceremonial holder, the priests would toss the bodies down the steps (and if you’re thinking this is as bad as religious rituals can get, let me break the news to you that cannibalism was the next step in the process).

Priests and nobles also shed their own blood to honor the gods, using thorns to pierce their tongues, ear lobes, and genitals, which I imagine significantly reduced the number of people wanting to become ordained.

While even an ordinary day in the Aztec Empire was likely to include a lot of death, if it was a special occasion, the temples literally ran with blood. For example, when the Templo Mayor, the major sacred site in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, was inaugurated in 1487, as many as 80,000 victims were sacrificed. Even the conquistadors were sickened by the carnage—-and if you can gross-out a Spanish conquistador, you know you’re at Olympic-levels of blood-letting.

One of my reactions to learning about Aztec religious traditions, I must admit, was a feeling of gratitude. Any member of an established faith must sometimes apologize to the larger world for its crimes and excesses, of which every religion has quite a few. Christianity has the Crusades and the Inquisition, for example, and even the peace-loving Buddhists have an embarrassing parade of charlatan gurus. But just imagine you’re an Aztec priest at a dinner party with visitors from out of town:

“And what do you do for a living?” they ask.

“Let’s have dessert on the patio!” is probably the best response.

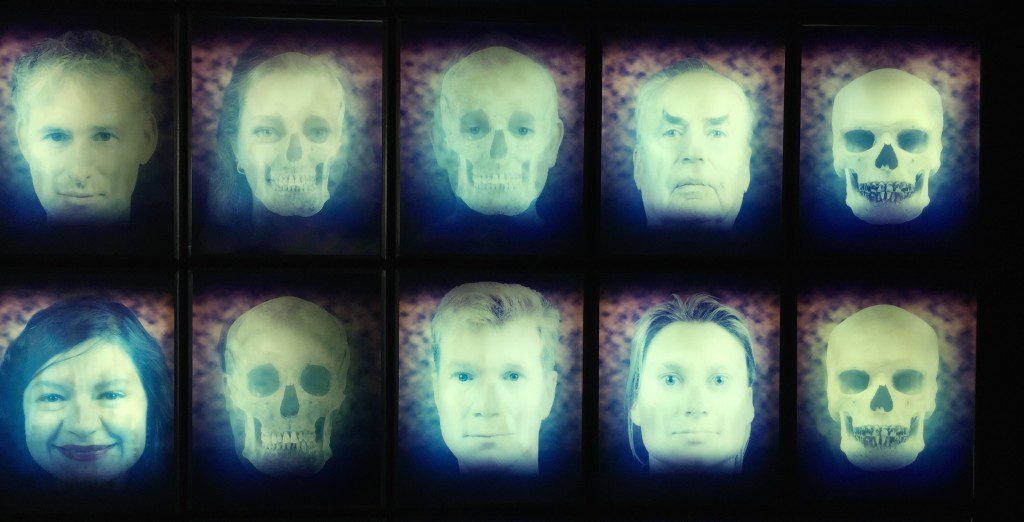

At the National Museum of Anthropology, I remember being transfixed by a multi-media installation that vividly conveyed a central truth of Mexican culture. A wall full of videos displayed people’s faces, smiling and laughing, but as I stood there they gradually were transformed into skulls.

The Mexicans know better than most cultures that even in the midst of vibrant life, death is always present, just beneath the surface.

Next post: The Templo Mayor, the Aztec Ceremonial Site in the Heart of Mexico City

Stay in touch! Like Holy Rover on Facebook: