One of the things I love best about my work is the chance to meet spiritual leaders in a wide range of traditions. Of all the people I’ve interviewed, Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson is one of the most interesting.

Hilmar is a well-known musician, film composer and art director in Iceland who has received a host of awards, including being named European Film Composer of the Year in 1991. But I wanted to talk to him because of another role he plays: allsherjargoði, or chief priest, of the religion Ásatrú, which is a revival of belief in the Old Norse gods and goddesses. On a gray morning in Reykjavik near the end of our stay in Iceland we spoke for nearly an hour about Icelandic history, its holy places, and what it takes to bring a dormant religion back to life.

Hilmar began by sketching a brief history of how Christianity came to be adopted in Iceland in the year 1000. “There was huge political and economic pressure to convert,” said Hilmar. “But I think it’s interesting that when the chieftains were trying to discern the way forward, they did a pagan ritual to decide. And even after Iceland became officially Christian, many people continued to follow the older traditions for several centuries.”

After that, the stories of Odin, Thor, Freyja and their divine kindred were primarily kept alive in the literature of Iceland, particularly in The Poetic Edda and The Prose Edda

(collections of Old Norse poems and stories). “Under the guise of teaching literature,” explained Hilmar, “people learned the old myths and stories.”

The modern revival of the religion began in the 19th century, influenced by the Romantic Movement in Europe and a revitalized sense of Icelandic national identity. In 1972 the Icelandic government recognized Ásatrú as an official religion, giving it legal authority to conduct weddings and burials. Today about 3,000 people are officially part of the Ásatrú community.

One of the things I found most interesting about our discussion is learning of the intertwining of Celtic and Norse traditions in Iceland. DNA analysis of people who lived in Iceland at the time of its settlement in the ninth and tenth centuries have revealed that about 70 percent of the women were Celts from the British Isles. “They brought with them their stories and beliefs,” said Hilmar. “Women are often the ones who keep culture alive, because they’re the ones who teach the children. Icelandic culture owes nearly as much to the Celts as to the Norse.”

Hilmar has had a ringside seat for the revival of Ásatrú, for when he joined the community at the age of 16, he was number 36 on its official registry. He said that in its first decades Ásatrú remained small and was viewed skeptically by many Icelanders, but eventually public opinion changed.

“Slowly people began to see we were serious,” Hilmar said. “Today we are the largest non-Christian denomination in Iceland, and there’s considerable interest in what we do even if people aren’t official members. About 42 percent of Icelanders describe their religious viewpoint as pagan. I’m happy to say that our relations with Christian leaders have improved as well. There’s a sense of mutual respect between us.”

There are four main holidays in Ásatrú: the winter and summer solstices, the first day of summer, and a mid-winter celebration called Thorrablot honoring the god Thor. There is no sacred text, but rather a set of precepts that include tolerance, honesty, honor and respect for the cultural heritage and natural world of Iceland.

“Fundamentally, we’re a nature-based religion,” said Hilmar. “In Iceland, we’re humbled by nature every day. The land is active. You can feel it beneath your feet. It’s easy to feel awe here.”

As high priest, much of what Hilmar does are the ordinary but important rituals of any religion: marriages, funerals and naming ceremonies for babies. Even in our brief time together, I could sense that he is a person of warmth, strength and integrity, someone who has done his spiritual homework.

When I asked Hilmar if there were some sites that are considered particularly holy in his tradition, he named three (all of which, I’m pleased to say, we had visited on our tour of Iceland):

Thingvellir is the place where representatives of all the tribes of Iceland began meeting once a year beginning around 930. The yearly assembly continued to 1798. In 1944, the nation gathered at Thingvellir to celebrate Iceland’s independence from Denmark. The site is also significant for its geology, for it sits on the fault line between the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates. “Thingvellir is the spiritual and symbolic heart of Iceland,” said Hilmar. “When you’re there, you can feel that it’s a place of power.”

The Snæfellsnes glacier lies atop what is widely regarded as the most beautiful mountain in Iceland (as with many of the peaks in Iceland, a volcano simmers beneath the ice). In the Icelandic histories known as the Sagas, Snæfellsnes was identified as an opening to the underworld, a tradition that inspired Jules Verne to write his novel Journey to the Center of the Earth. Mary’s Well, which I described in my previous post, lies at the base of Snæfellsnes.

Helgafell, located on the north coast of the Snæfellsnes peninsula, is a low-lying mountain that is also mentioned in the Sagas. In ancient times it was a pilgrimage place particularly for those nearing death, for it was believed to be an entry point into the afterlife. It was said that from its peak, one could sometimes see Valhalla, the paradise of warriors. Today people climb it in hopes of being granted three wishes, provided they follow these rules: As they ascend, they cannot look back. They must walk in silence. And they can never reveal to others what their wishes were.

Like a volcano of great power hidden under a blanket of snow, the Norse traditions underlie much of Icelandic history. The Icelanders were pagan far longer than they’ve been Christian, and today as Christianity wanes in much of Western Europe, it’s intriguing to see the ways in which these older traditions are resurfacing.

Would an ancient Norse warrior recognize the rituals of Ásatrú? The question gets to the heart of the challenges of reviving a religion. Because the culture of Iceland has changed so dramatically (no more chieftains fiercely guarding their honor or long boats setting off to raid foreign shores), simply copying the practices of a former era is not possible. How can a person believe in Thor as a thunder-maker if one understands the physics of lightning? But I think Ásatrú is saving the best parts of those old traditions–their deep respect for the natural world, their sense that there are powers far beyond human understanding, and their appreciation for the myths and stories that shaped the Icelandic world for centuries. And like any good religion, Ásatrú provides community and meaning for its followers and a guide for navigating the transitions of life: birth, marriage and death.

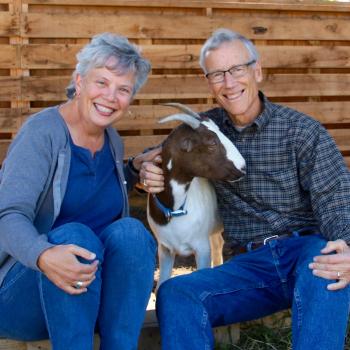

I know that when Bob and I stood on the top of Helgafell, that windswept promontory felt like many other holy spots we’ve visited–a thin spot, as the ancient Celts would say, where the boundaries between worlds is transparent. Like countless pilgrims before, we had followed the simple rules, which are likely a watered-down form of older and more complicated rituals. But I was struck by the spiritual truths embedded in those instructions: Don’t look back or dwell on the past. Meditate in silence to discover what you most desire. And keep the innermost yearnings of your heart private.

The picture below shows what we saw from the top of Helgafell. Perhaps it’s only because of my Scandinavian heritage, but for a few exquisite moments, I had no difficulty at all in believing I was looking at Valhalla.