Until recently, the term “Shaker” brought two things to my mind: a song and a chair.

The song was “‘Tis a Gift to Be Simple,” and the chair was a ladder-back piece of furniture I vaguely remembered seeing in a museum somewhere.

But after visiting Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill in Kentucky, I now know much more about the Shakers—and I’ve become fascinated by this quirky and creative community, one of America’s most intriguing religious groups.

You might think of the Shakers as hippies without the sex. Consider this: they lived communally, practiced ecstatic dancing and singing, and believed in gender and racial equality during an era when women and slaves were seen as chattel. They thought that God was both male and female, and also believed that when Jesus returns, he’ll come back as a woman. It’s no wonder the Shakers attracted skepticism and controversy during their heyday in the nineteenth century.

If it wasn’t for that celibacy thing, the Shakers might still be around today (well, there are actually four Shakers left in Maine, but there’s little hope they’re going to start attracting a lot of new members).

The group began as an offshoot of the Quakers in 18th-century England (celibacy was a bridge too far for the Quakers, too). The splinter community called themselves the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing. Interestingly, both of these names–the Quakers and the Shakers–were originally derogatory terms given to them by outsiders, but which the groups later adopted as their own.

In 1773 their leader, Mother Ann Lee, received a divine command to take a group of believers to the New World. Just eight people followed her lead, but they were remarkably successful in planting the religious community in new soil. They established 21 villages from Maine to Kentucky. All followed a similar communal pattern, with members giving up their property once they had completed a novitiate period.

If a married couple joined, they agreed to live as brother and sister. Any young people in the village, whether they were the children of members or orphans that the community took in, lived in dormitories.

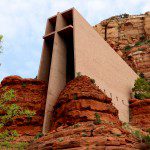

Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill is the largest historic site associated with this religious group. Located 25 miles southwest of Lexington, Kentucky, it was founded in 1805. By 1823 it encompassed 4,500 acres and had nearly 500 members.

“It was a thriving community,” explained the guide who led Bob and me on a tour of the village. “Their standard of living was much higher than that of the surrounding area–in fact, they had running water before the White House did. Everyone was literate, because they wanted members to be able to read the Bible. It was a remarkably egalitarian community, too, with people rotating through the various jobs of the community every six weeks.”

Let me put it this way: I’d rather have been a Shaker in 1823 than a typical frontier woman, burdened by childrearing and relentless, backbreaking work.

Women, in fact, were co-leaders in the village, sharing equally in all decisions. During an era when the average woman in Kentucky had two dresses, in Shaker Village the women each had ten. In 1840 the average life expectancy was 50, while in Shaker Village it was 70. A big reason was that the women were childless, so none of them died in childbirth and their infants didn’t die of disease. But even aside from that, the villagers had abundant food, good hygiene practices, and strong social support. They cared for their sick and elderly, which also helped them attract new members.

The Shakers, in Kentucky and elsewhere, were known for their business acumen. In the eastern villages, their well-made furniture fetched top prices. In Kentucky, Pleasant Hill earned money by selling straw brooms, seed packets (the Shakers were the first to sell seeds in this way), medicines and tonics, jams and jellies, and agricultural products.

“I think it’s somewhat confusing for our visitors, because Pleasant Hill is restored to its 1840 appearance and so they think the Shakers were like the Amish,” said our guide. “But actually the Shakers had no problem with new technologies–in fact, they embraced them.”

It was technology, however, that led to the decline of the Shakers (well, that and the celibacy rule, which made it hard to attract and keep new members). Their small, cottage industries couldn’t compete with the cheaply made products manufactured by the Industrial Revolution. As the national economy changed, the Shaker villages lost members. By 1910, Shaker Village in Kentucky was down to 10 members, who sold the property with the proviso they could stay there for the rest of their lives. The last sister died in 1923.

Thankfully, in the 1960s a group of historians led the drive to purchase the land and restore the buildings. Today Pleasant Hill has 3,000 acres and 34 original buildings. With its period architecture, fences made of stacked stones, and tranquil atmosphere, it’s still a sacred place—a refuge from the busyness of the modern world.

Guests can visit just for the day or stay overnight in one of the historic buildings. They can take a cruise on the Dixie Belle Riverboat on the scenic Kentucky River, ride in a horse-drawn wagon, and have a meal at The Trustee’s Table (some of the produce will likely have come from just a few hundred feet away).

Or they can do yoga (“if the Shakers were around today, they’d offer yoga,” explained our guide). Or learn about bee-keeping. Or take a hike on the property’s woodland trails.

“We’re trying to broaden our offerings,” explained Amy Bugg, director of marketing and communications. “Shaker Village isn’t just about the past. We want people to see this as a place of refreshment and renewal for contemporary people as well.”

We didn’t get the chance to stay overnight, but I loved wandering around the village on a beautiful fall day. We visited with a pair of horses, learned about raising chickens from the farm manager, toured exhibits on the history of Pleasant Hill, and rode on the Dixie Belle.

But my favorite activity was a presentation called “20,000 Hymns.” Held in the village’s spare, sparsely furnished church, it was led by Carys Kunze, a staff member with a specialty in both history and music. She announced the start of her program by singing from the front door of the building, sounding like an angel who had briefly landed on earth. It was quite an astonishing performance, and her program hadn’t even started.

Once inside, she told us about the important role that music played in the Shaker villages. “All music was sung acapella, with no harmonizing,” she said. “It was deliberately simple, with no divisions, just like the community was supposed to be.”

We learned that every village had its own set of songs, though some were also shared between villages.

“Their services didn’t have a sermon and instead had dancing, singing, and the sharing of testimonies,” Kunze said. “Members of the community believed that the distance between heaven and earth is very small and that angels attended their services. They would go into trances as they sang and danced, and some people would receive messages from heaven. Their worship didn’t have a time limit and would often last for two or three hours. One time, a service even lasted 23 hours.”

Then she invited us to sing along with her, assuring us the building has fantastic acoustics. “Go ahead and sing, ” she told us. “You’ll sound better here than anywhere else you’ll ever sing.”

She was right. And there might well have been an angel or two who joined in, too.

The Shakers did a lot of things right, didn’t they? Life was meant to be filled with worshiping, praying, singing, and being in community. We can learn something from them, here in this peaceful village in the rolling hills of Kentucky.

For more information see Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, Kentucky.

Stay in touch! Like Holy Rover on Facebook: