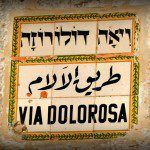

- On the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem (Lori Erickson photo)

Today I’m posting a sermon I gave on Sunday in my home church–a bit longer than the usual Holy Rover fare, but I hope it might strike some chords for those of you on a Lenten path. (And if you’re interested in seeing the Griefwalker documentary I refer to, you can view it by clicking on the link).

I’ve been fortunate to travel to many interesting places for my work, but in January I had a trip that was one of the most fascinating journeys I’ve ever taken, a 12-day tour of Biblical sites in Israel.

During Lent, I’ve found myself thinking often of a place that didn’t appeal to me that much when I was there. But as time passes, the more significant my visit to the Via Dolorosa seems.

The Via Dolorosa, which is Latin for the “Way of Sorrow,” winds through the heart of the Old City of Jerusalem. It follows the journey made by Jesus from the Roman judgment court to his crucifixion. Walking the path is an act of devotion made by nearly every Christian pilgrim to the city. The route begins in the Muslim Quarter and includes fourteen stations, several of which have chapels for meditation and prayer. It ends in the Christian Quarter at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the place where tradition says Jesus was crucified and laid in a tomb.

Historians say that the Via Dolorosa probably does not mark the exact route followed by Jesus on his way to the cross. But as with so much in the Holy Land, exactitude is not the point. Jesus did walk through the city of Jerusalem on his way to be killed, and then, as now, the Old City was a bustling place, full of the heady aroma of spices, the playful antics of children, and the banter of shoppers. The everyday activities of the world did not stop for his tortured journey.

Jordan Smith, a professor of religious studies who visited Trinity a few weeks ago for one of our Lenten courses, made it clear in his presentation that Jesus’ last journey would not have seemed remarkable to most of the citizens of Jerusalem. The Romans crucified thousands of Jews during this period—so many, in fact, that for efficiency’s sake they likely kept the upright portions of crosses set up outside of the city walls. Smith explained that crucifixion had two purposes: to kill the victim and also to send a message to the living. This is what happens to troublemakers, the array of dead bodies would proclaim.

So Jesus’ last walk through the city streets would not have been that unusual. His few remaining followers were in despair, of course, but most of the rest of those who had followed him on Palm Sunday had already abandoned him. This sort of thing happened again and again to charismatic leaders in Jerusalem. Their stars would brightly shine, they’d attract followers, and then the might of Rome would crush them.

So really, one could argue that the distractions along the Via Dolorosa today are, in their own way, authentic. The Old City does not keep quiet for the pilgrims who follow the pilgrimage route today, just as it did not pause when a beaten man walked its streets 2,000 years ago.

I know that on my own walk along the Via Dolorosa, I found myself distracted and often irritated by the bustle of the crowds and the calls of merchants eager to sell knick knacks. It was a bit like trying to have a spiritual experience in the middle of a shopping mall.

But that’s the problem with Lent, is it not? Our journey through this holy season is also marked by distractions. We want it to be sacred time, but our ordinary lives keep getting in the way. Deadlines loom, bills need to be paid, commitments must be met. We glimpse the Via Dolorosa of Lent only dimly, its power and mystery obscured by the busyness of our ordinary lives.

Here at Trinity, we hang depictions of Jesus’ last hours on the walls of our church during this season. Historians say that this tradition has its origins in Jerusalem’s Via Dolorosa. Pilgrims to the Holy Land brought this devotional practice back to Europe, creating Ways of the Cross in countless churches. To this day, most Roman Catholic parishes have this as a permanent installation, often in a garden outside the church.

One could argue that this is a misplaced act of devotion, that it focuses on despair and death rather than the resurrection of Jesus. And perhaps sometimes this does happen, this focusing too much on the darkness of the Jesus’ last days rather than its message of hope. But I would argue that the Via Dolorosa, the Way of the Cross, is also an essential part of the Christian story, one worth meditating on in this season especially.

Think of the words of Jesus from the Gospel reading this morning: “Whoever serves me must follow me, and where I am, there will my servant be also.” He invites us to be present with him on his Way of Sorrow, to help us learn its lessons.

In accompanying Jesus along this path, it helps us recognize the other forms in which the Via Dolorosa appears. Walk through the hallways of a hospital, especially on the surgical and cancer floors, and you’re likely to see people on their own Via Dolorosa. Or browse through the petitions left by passersby in the prayer kiosk outside our front door. The people walking by each day are often on a Way of Sorrow, weighed down by worries for loved ones and themselves.

The point of the Via Dolorosa, wherever it is, is that we do not walk it alone. We know that God is with us in our brokenness, failure and despair, because Jesus walked this path first. Sometimes Jesus is carrying the cross, and sometimes we carry it.

This Friday, we’ll be showing a powerful documentary, Griefwalker, in the Parish Hall as part of our Lenten programming. The movie is about Stephen Jenkinson, a theologian and social worker who has been at the bedsides of more than 1,000 people as they died. It’s an eloquent meditation on the lessons to be found in grief and dying.

One of the most powerful scenes in the movie is a conversation between Jenkinson and a woman in her last days of life. She and her husband have a blended family with children from previous marriages, and she worries about how the family will stay together once she is gone. With gentleness and compassion, Jenkinson tells her that her family’s capacity to be a family after her death will in large part depend upon how she dies. The table she sets will determine how they will be able to build their lives without her.

And then Jenkinson goes on to say that we cannot truly love something or someone until we also love its end. He reminds her that the beginning of a marriage foreshadows the time when the couple will part. The birth of a child means that one day that life will come to an end. If we love the first part of the journey, he says, we also have an obligation to love its end.

That is why the dying have so much to teach the living, and why it is a mistake to try to hurry through the last stage of life without recognizing its sacredness. Perhaps you have been at the bedside of a dying loved one and have seen for yourself the holiness that can be present. Or maybe you have witnessed a death that seemed like a terrible travesty because of medical interventions that turned a natural process into a long, drawn-out agony.

One could say that our wish to avoid contemplating the Via Dolorosa is another aspect of our fear of death. Our impulse is to not look too closely at the stations of the cross as we hurry by, not realizing how much they have to teach us.

Listen again to what Jesus had to say in our reading from this morning: “Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.”

So I urge you to enter into these last two weeks of Lent as deeply as you can, for these days of solemn reflection are passing quickly. I especially hope you can take part in the drama of our Holy Week services, for they are the richest nourishment that the church offers.

On my own journey on the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem, I eventually made my way to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It is an ancient sanctuary, lit by flickering candles and full of ornate altars and gilded icons. It is not so much a church as it is a series of shrines, each marking a different point in the last hours of Jesus’ life. And at the center of the building is a long line of pilgrims standing in front of the sepulchre, patiently waiting to enter the tomb itself.

That is where we are now, here in the final weeks of Lent as Holy Week approaches. It’s not a bad place to stand, actually, here outside the tomb, confronting the reality of Jesus’ death and of our own deaths. Let us rest here awhile as we pray that we may receive the wisdom that can come to us on the Way of Sorrow.