[This is a repost of one of my favorite posts from 2015 over at www.spiritualecologyalliance.org]

What is Spiritual Ecology? And what relationship do spirituality and ecology have with place?

What is Spiritual Ecology? And what relationship do spirituality and ecology have with place?

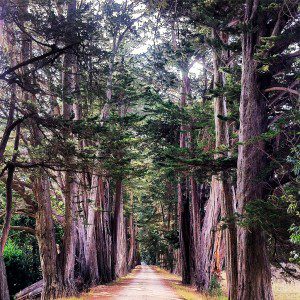

My current residence, Vancouver, BC is only the latest layer in a deep cultural geology that emerged after the glaciers melted from what is now being called the Salish Sea—the watersheds that drain into the Puget Sound, Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Georgia Strait. Coast Salish peoples number over 60,000 souls today making up over 50 tribes, bands and kin groups. By many of their own accounts, they have dwelt in this place from the beginning of time. I cannot speak for them, but I know that for many, place is not an inert geometric space that has over the years produced fond feelings of attachment; it is not an object outside themselves that they have learned to appreciate through meaning-making. Place is the ground of their being; it is an oikos—a dwelling-place, a habitation. The sea, mountains, forests, salmon, deer, plants, air and sky are woven into their be-ing. The stories, myths, rituals, ceremonies and dangers spoken of by First Peoples are not metaphors projected onto otherwise meaningless physical terrain; they are the grammar of dwelling; they do not make up a worldview, they make up the world (See Eduardo Kohn, 2013, How Forests Think).

For my people, the new-comers, the settlers, the children of colonials seeking a better life under the watchful eye of God and Progress; the Salish Sea too nourished our bodies, but also our love of money. Only later did it nourish our souls. Having laid our hands to ax and plow, we were proud of our work and our sweat, we dedicated it to God, built places of worship in His name. We brought ‘savage’ peoples a saving ‘religion’. We too were immersed in not only a worldview, but a world; one that we believed would bring peace to earth and eternal life to souls. Only within the last few years have we begun to wake up to the savagery of our world; to the violence of what we thought was love, to the folly of what we thought was progress. We the learned, have much to learn, much to undo, and much to apologize for.

One way we sought to right our wrongs was by offering up large swaths of the land to healing, contemplation, beauty and solitude. Today, the Salish Sea has become our Spiritual Ecology too. In the 1800s we fell in love with Nature and sought to protect it from our advancing cult of Progress. But our Spiritual Ecology had a flaw, a difference to that of the First Peoples: it was dualistic. By dualistic I mean that the West dwells in a schizophrenic world of distinct domains: culture and nature, subject and object, traditional and modern, spirit and matter. This orientation to the world separates our dwelling places from our soul places: work and worship, city and country. Nature became a place that we went to after a long day; a refuge from civilization, a recreation. Non-humans became objects for our perception and manipulation (whether that be for food, money or beauty). Being ejected from the Garden, we tried to bring the Garden back to us through protected areas, National Parks and National Forests. Ecology meant Nature, and Spirit meant the non-material aspect of our all too materialistic world.

This ontology is killing the world. It is killing our Religion. It is killing our Souls. But things are changing.

For many of the rising generation, spirit is not so much a shimmery version of ourselves that lives inside us like the driver of a car. Spirit is anima, breath. Spirit is Life. Being spiritual is nothing more or less than being fully alive; being present to life and it’s flourishing. The religions most of us grew up with felt like rules and beliefs, and in-group out-group posturing. But within all religions there is always a spirituality of life. Religion, religare—to bind together—can be about our connection to God and each other, but also about our connection to Life. Religion properly practiced is a response to life. It is not an answer to the question ‘what is the meaning of life?’, for as Philosopher John Caputo would say, life is the meaning of life.

Ecology is not Nature as a separate domain of reality. Ecology is the scientific study of organisms in their environment; but it is so much more than this, for there is no such thing as an environment. There is only a great web be-ing, an intricate web of life, life-ing. All life, even the life that is not yet life in the air, rocks food and water; even the life no longer living. Being present to life is being present to both the beauty and the pain of life. Yes there is tremendous suffering in the web of life and death, but even in the predator, disease and parasite there is life and the continuation of life, the evolution of life, the creativity of life. Spiritual Ecology then is a celebration of life in all aspects, both beauty and pain. A Spiritual Ecologist mindfully witnesses to this beauty and pain and acts accordingly.

Spiritual Ecology is one part perception, one part practice and one part ethic.

Perception: For a long time in the West, Spiritual Ecology was about appreciating the beauty of Nature, or protecting Nature from Culture. In light of Climate Change, we are realizing there is no such thing as Nature. This is not to say that the world does not exist, or even that it is a social construction; but that if we are looking for hard facts about the world, a place, a thing called Nature outside and apart from Culture it is just not there. Nature is a disembodied spirit, a ghost that has haunted us for 200 years. But our perception is changing, through both the wisdom of religion and the propositions of science we are waking up to a different world. Theologian John Caputo gives us a glance of that world:

“The cosmos opened up by Copernicus collapse the distinction between ‘heaven’ and ‘earth’…The earth is itself a heavenly body, one more heavenly body made up of stardust, as are our own bodies. We are already heavenly bodies, which means that ‘heaven’ and ‘hell’ must report back at once to headquarters for reassignment, where they turn out to be ways of describing our terrestrial lives here ‘below’. Every body—everybody, everything—is a heavenly body. Heaven is overtaken by the heavens. Dust to dust, indeed, but it is all stellar dust. Our bodily flesh is woven of the flesh of the earth, even as the earth itself is the debris of stars, the outcome of innumerable cyclings and recyclings of stellar stuff, all so many rolls of the cosmic dice. We are not ‘subjects’ over and against ‘objects’, but bits and pieces of the universe itself, ways the world is wound up into little intensities producing special effects of a particular sort in our bodies in our little corner of the universe” (Caputo, 2011, The Insistence of God, 175).

Caputo expresses a deep call calling from beyond our Western world. Science and Religion, who have been temporarily separated due to irreconcilable differences, are starting to warm up to one another again. We need them both, but not as complementary institutions concerned with facts on one hand and values on the other; not as two coins that add up to 1.00, but two sides of the same coin. There is no objective knowledge outside of human experience, and human experience is not the unreliable black box subjectivity. Our bodies, minds, souls and science emerged from this planet. As Caputo again states, “our power of vision, as well as the particular structure of the color spectrum available to sight, is a direct and precise effect of the astronomical composition of our sun, which has set the parameters of vision which we and other animals forms have evolved. To ask whether what we see, as if it were inside our head, ‘corresponds’ to what is out there, ‘outside our head’, is to ask a question not only without an answer but without meaning” (Caputo 2006, The Insistence of God, 176).

Spiritual Ecology then does not involve going to Nature to find spiritual meaning or connection. This keeps nature separate from culture, spirit separate from nature. Spiritual Ecology is cherishing life, and witnessing to the beauty and pain of the world wherever we are. Yes it is about interconnection, but also the connections that hurt, that threaten us with harm; and the connections that threaten others. The virtue of Christian hospitality is not only welcoming the known, the familiar; but the wholly (Holy) other. Being open to life is to see it, really see it, in all its complexity and to let our lifeways emerge accordingly. This can happen in the ocean, the forest, the savannah, a farm, a city, or a slum. Spiritual Ecology is our communities, our places of worship, our prisons, our hospitals, our schools, the blackberry patches on the side of the roads. It is wherever we are present to the unfolding of life.

This presence is not the appreciation of an aesthetic object. Anthropologist David Abrams helps us shift our gaze in this respect: “To touch the course skin of a tree is thus, at the same time to experience one’s own tactility, to feel oneself touched by the tree. And to see the world is also, at the same time to experience oneself as visible, to feel oneself seen” (Abrams 1996, The Spell of the Sensuous, 68). This is not a relationship between knowing subject and known object, it is the relationship between two waves in an ocean.

Practice: Once we realize with Theologian Thomas Berry that “The natural world is the maternal source of our being…the larger sacred community to which we belong.” (Berry 2006, Dream of the Earth, 81), our spiritual practices will reflect that fact. I was raised in the Mormon Church. I greatly admire the Mormon faith and its people; however, my own religious path has called me to a more Contemplative Christianity. For me, the Mass, the Eucharist, prayer, churches and the saints all enhance and give particular form to my celebration of life. Yes there is much to criticize in the Christianity, but through liturgy that centers on the person of Jesus, my appreciation for life, my love for others has only increased. To say that Christ is in the bread and wine of the Eucharist, is to ritualize the presence of Christ in the cosmos from the moment it flared forth at the Big Bang. To shout Christ is Risen, Alleluia! at Easter is to ritualize the emergence of tiny beautiful buds from the limbs of every tree. To bring the body of Christ into my body prepares me to see God in everything I eat, in everyone I come into contact with. This celebration will be different for each person, each tradition.

Ethic: Once we realize in body and mind that we are the world we seek to experience, our actions should not take the form of a rigid dogma, a Puritanical obsession with recycling or turning off the lights. I do not mean that these are wrong, I only mean that they are not ethics, they are dogmas. Green purchasing is just another marketing scheme to Western individuals that want to consume an identity. We do it all the time. I do it all the time. An ethic is a practice that carries moral weight, it is more complicated than rule. Anthropologist Richard Nelson, writing of his connection to an island off the coast of British Columbia, captures the spirit of how an ethic might emerge for a Spiritual Ecologist:

“There is nothing in me that is not of earth, no split instant of separateness, no particle that disunites me from the surroundings. I am no less than the earth itself. The rivers run through my veins, the winds blow in and out with my breath, the soil makes my flesh, the sun’s heat smolders inside me. A sickness or injury that befalls the earth befalls me. A fouled molecule that runs through the earth runs through me. Where the earth is cleansed and nourished, its purity infuses me. The life of the earth is my life. My eyes are the earth gazing at itself…I am the island and the island is me” (My emphasis, Nelson 1989, The Island Within, 249, 250).

All of our decisions have consequences that eventually return to us. How and whether we are able to turn this culture around is an ongoing debate, but it will require more than carbon markets, stricter regulations, expanded protected areas, or planting more trees. It will require a deep shift in our perception and practice of the world from which emerges an ethic that refuses to see one more species go extinct, one more child starve, one more woman abused, one more First Nations’ sacred site destroyed, one more mine tailings pond burst, or, most recently, one more fuel leak in the ocean. How we get there is part of a long difficult conversation. Spiritual Ecology is only one aspect of that conversation, but it needs to be part of it.