Summary (Spoiler Alert)

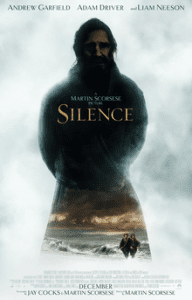

Martin Scorsese, himself a Catholic, recently released his film version of Shūsaku Endō’s 1966 novel Silence. The novel is set in 17th century Japan, where Jesuit Priests Sebastião Rodrigues (played by Andrew Garfield) and Father Francisco Garrpe (played by Adam Driver), are smuggled into Japan to care for the Kakure Kirishitan “Hidden Christians” that have been driven underground by the hostile Shogunate of Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the year 1639. The Priests are also looking for Ferreira (played by Liam Neeson), a former priest, who is rumored to have apostatized and to be living with a Japanese wife in Japanese society. Both the novel and the film explore with brilliance questions around suffering, and God’s silence in the face hardship.

In the novel, Christians who have been discovered are forced to trample on a fumie or a crudely carved image of Christ. However, this proves not to be enough for the officials who want to eradicate the religion completely. They force Father Rodrigues to watch Christians being tortured until he himself renounces his faith, seeking to put an end to the public practice of Christianity in Japan. Rodrigues, like many zealous missionaries, hoped for a glorious martyrdom, but instead is faced with watching the gruesome and cruel torture of humiliated Japanese Christians. His journal entries jump between zealous commitment and questioning doubt. Should he hold out? Is he being selfish? Should he recant outwardly simply to save the lives of those who suffer needlessly? Why was God so often silent in the face of suffering?

The Inquisitor and his henchmen storm villages and round up accused or suspected Christians. However, the Inquisitor himself is a completely perplexing character. Played by Japanese actor and comedian Issei Ogata, he seems to want to subvert the role of a conventional evil villain for more of a trickster-like character who is playful and even good humored as he carries out his duties of systematically outing Christians and torturing them into recanting all for loyalty to his superior the Emperor. Another important character, Kichijiro (played by Yōsuke Kubozuka), is a Christian who continuously recants and denies his faith to save his life, but who seeks absolution from Rodrigues each time, even when he betrays Rodrigues into the hands of the Inquisitor. He is an obvious reference to Judas Iscariot and a lost soul.

At the climax of the film, Rodrigues is faced with trampling the fumie in order to save five Christians being tortured. As he stands over the image, the silence is finally broken and Rodrigues hears a voice say: “You may trample. You may trample. I more than anyone know of the pain in your foot. You may trample. It was to be trampled on by men that I was born into this world. It was to share men’s pain that I carried my cross.” Rodrigues tramples the image, collapses to ground, and the people are saved. He then lives the remainder of his life as a hidden Christian in Japan, taking a wife, and even helping discover those who would smuggle Christian icons and paraphernalia into the country.

Despite the wrestle Rodrigues has with human suffering, I wonder how much sympathy he will get from today’s audience, who are perhaps less zealous in our belief that any ideology is worth dying for. Or, a generation who has had the benefit of anthropology to realize that each culture is unique and distinct, and that declaring one culture superior to another is essentially a pluralist heresy. It left me wondering, why didn’t Rodrigues just leave Japan? Why wasn’t that an option? Could the character really not conceive of keeping his faith intact back in Portugal? Why was the truly noble thing to do to stay in Japan as a secret Christian for the rest of his life betraying his vows of celibacy, poverty and obedience?

Christian Mission and Cultural Relativism

Here are several responses to this point of the plot, which seem not to make sense. On the one hand, the Japanese establishment were correct when they saw Christianity as an existential threat. Christianity as it was conceived in the early days of the church was revolutionary. If Christ was resurrected, then Jesus, not Cesar was Lord, and everything was turned upside down.

During one scene, Father Rodrigues is speaking with the Inquisitor who is trying to convince Rodrigues that Christianity may very well work in Portugal, but like a tree in a swamp, it just cannot flourish in Japan. Rodrigues counters that if truth is universal, it doesn’t matter if we are in Japan or Portugal. But how can we tell the difference between universal truth and the cultural trimmings that come along with it? Unfortunately, missionaries were often preaching not just the ways of Jesus, but the ways of the West as well. Certainly God is universal, but according to the Christian story, he chose to become human in a very particular place and time.

Is Jesus the icon of the Christ that we must look for in every culture? Or is Jesus Christ the one true image of God for all human beings everywhere?

This got me thinking about another religion that was introduced to Japan, only 100 years or so before Christianity. Buddhism, brought by Buddhist monks along the Silk Road, and to Japan by traders, was slow to spread and many of the Japanese establishment openly opposed it because of its perceived challenge to the dominance of Kami, or nature spirits, which are venerated in Shinto, the indigenous spiritual tradition of Japan.

There was after all, a general mistrust of foreign ideas throughout the history of Japanese feudal and imperial rule, and Buddhism, as malleable as it was, was still foreign. Buddhism initially found some adherents, but like Christianity in the Mediterranean, it didn’t really take root until it was adopted by the Roman Empire. In Japan, one of the first official recognition came with the Empress Suiko (554-628) who encouraged the Japanese people to adopt the religion along with their Shinto traditions. The Seventh Century Soga clan was also instrumental in its spread. They favored Confucian governance, but Buddhist spiritual practice and they even placed Buddhist statues in some Shinto Shrines.

After this time, various sects of Buddhism waxed and waned depending on the whims and interests of the Rulers through the Common Era. But Buddhist Temples were often located near Shinto Shrines, allowing the two systems to develop and cross pollinate together. However, Buddhism was not safe, in 1868, long after the persecution of Christians had passed, a Coup ushered in what is called the “Meiji Restoration.” The new government sought to eradicate Buddhism because of its connections to the Shoguns, and Shinto again enjoyed official ascendency. An edict in 1872 even forced many Buddhist monks to marry, and agree to eat meat. Paradoxically, this was also the time when Christianity was officially legalized, and the State Shinto continued until Japan’s defeat in WWII.

Certainly Christianity and Buddhism differ, but I have always thought that Christianity would have been more successful if it had adopted a more diffusionist approach to mission. For example, today, 34 per cent of Japanese people consider themselves Buddhist, a number on the rise in recent decades. That is compared with the almost one per cent who consider themselves Christian. However, over 80 per cent of Japanese conduct funerals according to Buddhist tradition, and those same 80 per cent are just as likely to get married in a Shinto Shrine. Would it be totally unacceptable for a Japanese Christian to conceive of this kind of pluralism? Is it better for Christianity to just not be present if it is going to be blended with the cultural context?

The way Christianity was spread throughout the Western world’s various empires has always struck me as essentially anti-Christian. How could there ever be Christian conquistadors? Certainly Christ ask his disciples to preach the Gospel, but not with the sword. Is a zealous Christianity which was forced underground but uncompromised better than a syncretic Christianity in dialogue (rather than shouting at) the world’s cultural wisdom? To me the answer seems obvious. If Rodrigues wanted to be a zealous Catholic, he should have gone back to Portugal.

Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE) said in defense of his dialogue with Greek culture:

Philosophy has been given to the Greeks as their own kind of Covenant, their foundation for the philosophy of Christ. The philosophy of the Greeks contains the basic elements of that genuine and perfect knowledge which is higher than human (Miscellanies 6.8).

If Rodrigues wanted to be a humble Christian, he should himself have been silent before God’s great silence and listened to the wisdom of the Japanese tradition and culture with an open heart, seeking the seeds of Christ therein.