(This is a talk I gave at this year’s Women’s Conference at Brigham Young University.)

For Thanksgiving each of us in the family has to make a pie—because you can never have too many pies—and this year I tried for the second year in a row to make a banana cream pie. My pie the year before had been too runny. I was determined to follow the recipe exactly this time, so determined that I failed to notice I used a half cup of salt instead of a half cup of sugar as instructed. My custard was creamy, not too runny, just perfect, but when I taste tested it before pouring it into the crust, I gagged. Needless to say, my family got quite a kick out of this. My wife kept laughing and saying over and over, “A half cup of salt! Really? What were you thinking?!” Obviously I wasn’t thinking at all. I just lost the forest for the trees, trying so hard to follow the instructions that I failed to use common sense. I wish I could say that this was an isolated incident. I seem constitutionally incapable of following simple instructions properly. I am the same way with board games. I have learned that if I read the instructions or listen to others explain them to me, my mind goes blank and I lose interest, but give me a chance to start playing and to intuitively figure it out, the passion for competition lights within and I become a pretty fierce and capable competitor.

For Thanksgiving each of us in the family has to make a pie—because you can never have too many pies—and this year I tried for the second year in a row to make a banana cream pie. My pie the year before had been too runny. I was determined to follow the recipe exactly this time, so determined that I failed to notice I used a half cup of salt instead of a half cup of sugar as instructed. My custard was creamy, not too runny, just perfect, but when I taste tested it before pouring it into the crust, I gagged. Needless to say, my family got quite a kick out of this. My wife kept laughing and saying over and over, “A half cup of salt! Really? What were you thinking?!” Obviously I wasn’t thinking at all. I just lost the forest for the trees, trying so hard to follow the instructions that I failed to use common sense. I wish I could say that this was an isolated incident. I seem constitutionally incapable of following simple instructions properly. I am the same way with board games. I have learned that if I read the instructions or listen to others explain them to me, my mind goes blank and I lose interest, but give me a chance to start playing and to intuitively figure it out, the passion for competition lights within and I become a pretty fierce and capable competitor.

My point is not that God’s commandments are like a recipe, nor that gospel living is like a competition we strive to win. Presumably a recipe, if followed correctly by any individual, results in more or less the same pie, but in his intimate regard for us as unique individuals, God is not intent on churning us out like identical cookies cut from the same pattern. The fold of God is not a mold. As the body of Christ, we are all inherently valuable members with our own unique stories, gifts, and experiences. Nor is the point of gospel living to compare ourselves to see if we are staying ahead or falling behind others. Until we accept God’s unconditional love and our inherent worth, no amount of effort will be enough to prove our worthiness to ourselves. We will remain our own harshest critics, over-thinking and second-guessing our worthiness, constantly battling a sense of shame, and failing to forgive ourselves for things Christ has longer ago forgotten or failing to forgive others for things Christ already suffered for.

As a teenager growing up in Connecticut, I wasn’t so much a rebel as just the kind of kid who needed the space and freedom to figure things out on my own. I convinced myself that the question of God’s existence, let alone his possible interest in and love for me as his child, was simply unresolvable and unknowable. This allowed me the convenience of experimenting with alcohol and smoking with imagined impunity. I kept this up for a number of years. I thought I was protecting my freedom, but I was blind to just how reactionary and self-gratifying and therefore inauthentic my choices were, let alone the damage they were doing to my capacity to think clearly and act intentionally. The truth is, I was afraid, confused, and dangerously losing self-control. Somehow I confused commandments—and even the very idea of God—with coercion, conformity, and utter disregard for my individuality. But because I loved my parents and respected people at church and didn’t want to disappoint them, I thought I could keep it a secret.

Until one fateful Saturday morning of my senior year after I had been out the night before with friends when my father entered my bedroom, closed the door behind him, and pulled a chair right up next to my bed. He rubbed my back and spoke gently and said something like this: “Your mom and I have been worried about you. We are especially worried that you don’t feel comfortable sharing your life with us. You are old enough to be making your own decisions, and it pains us to think that a son of ours could live under our roof and not feel comfortable being honest about who he is or what he is doing. So I want to ask you some questions about what you are doing with your friends and I am want you to feel comfortable and safe being completely honest with me. Before I ask you these questions, I want to reassure you that I have no intention of punishing you. I only want to know the truth so I can know you better. I grew up in a much different world than you did, so I want you to help me understand what it is like for you.” So he asked me some questions, and without hesitation and with great relief, I unburdened myself of my story. When I was done, he told me he loved me and believed that I had the good sense to lead a good life. And then he said “I am not going to make any demands on what you do from now on. All I want to ask of you is that you trust us to tell me and your mother from now on where you are going with your friends and what you plan to do. We want you to be honest and to be safe. Can you do that?” I told him I could. That night I went into his bedroom and announced where I was going that night and I told him, “Dad, I won’t be drinking or anything else tonight. I won’t do those things anymore.” “Are you sure about that?” he asked. “Absolutely sure, Dad. I am done.”

My father wouldn’t want you to believe he was a perfect father. He is always the first to acknowledge his own weaknesses and mistakes, but on that day I think he had the perfect words and the perfect tone for me. He could have been angry, hurt, or taken it personally in some way. That would have been understandable. When I read the words “by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned and by kindness” (D&C 121: 41), I can say that I know exactly what that feels like. It was undeniable love and acceptance that rather than leaving me content with my sins unleashed my freedom to choose what deep down I always knew was right. This was freedom, of course, that I always had, that had been safeguarded since the foundation of the world by God’s plan and its cornerstone, Christ’s atonement. But real freedom is responsibility not impunity, and I wasn’t ready to accept it. My father’s generosity filled me with gratitude and every desire for sin departed. I wanted to be as courageous and faithful and loving as he had been with me. And so my conversion to the gospel began. A few weeks later when I was called into my Bishop’s office and offered the chance to serve as his first assistant to the priest’s quorum, I confessed all of my sins and gladly accepted the calling. I learned then that my spiritual father had also placed generous trust in me, by allowing me to choose the good for myself and by using gentle persuasion, not coercion or intimidation. Filled with gratitude for that love, I felt freed to serve him.

I believe it is an innate and even sacred desire within each of us to want to discover our own deep wells of passion, creativity, and self-determination. The problem is that when we are left to our own devices, our will can burst like a bull into a china shop. And in our mistakes, we compromise our own and others’ agency, but with God’s gentle guidance, our free will can authentically grow like a beautiful crescendo in music. In our disobedience God looks exactly the same, always asking nothing of us and always at a cool remove from the world even though we remain oddly convinced that he approves of our every whim. He is a dead and mute god created after our own image, guaranteed to prevent our development. But the God of our belief—although the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow—is so involved in our lives that he manifests himself perpetually in new and surprising ways. Belief in the living God is a relationship, a dialogue, that facilitates our growth and change.

I have learned through experience that I cannot afford to implicitly trust myself and my every instinct. I am, however, grateful for the freedom to gain that understanding through my own experience. We must understand for ourselves that we need instruction, correction, and assistance in rising above our limited understanding of who we are. And nothing quite inspires a desire to do right than to know in that moment of humiliation and vulnerability that a hand of mercy and forgiveness is offered to us. Jesus said he came so that we “might have life and that [we] might have it more abundantly.” Sin, then, is what prevents us from becoming our best selves and from using our will as effectively and as freely as possible. So in order to become more truly ourselves, we must have the humility to make Jesus the master of our lives.

So the question is, where does that willingness come from? It is from the experience of the love of God. King Benjamin didn’t stuff his listeners’ ears with commandments but he gave them a witness of Christ and of His mercies. His listeners became “children of Christ”; they were “born of him” (Mosiah 5:7). They said they felt “a mighty change… in our hearts, that we have no more disposition to do evil, but to do good continually” (Mosiah 5:2). Just as Adam and Eve had done when they departed the Garden of Eden with a new appreciation for the trust and mercy of God despite their transgression, King Benjamin’s listeners wanted to start over and make a covenant of obedience: “We are willing to enter into a covenant with our God to do his will, and to be obedient to his commandments in all things that he shall command us” (Mosiah 5:5). The lesson here is that we don’t browbeat people into obedience or simply assume it is enough to teach the truth. They need to experience a reason to feel gratitude for God. They need to experience love first. As John said, “we love him, because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19). Every sacrament prayer speaks of our desire to obey as a grateful response to the love we experienced at our spiritual birth.

This means that as a community of believers we bear a special responsibility to make that love palpable for everyone within the walls of our churches, our homes, and in our communities. Commandments learned in an unloving or unjust or judgmental environment where our agency is not respected and we are not unconditionally loved can be a form of spiritual abuse. How many of God’s children have been lost because of the pride, arrogance, or controlling manipulations of unrighteous dominion? If you are a victim of such abuse, it will be easy to confuse the message with the messenger and fail to see the love, the respect, and honor God’s commandments pay to your individuality. More benignly, in our anxiety to encourage others to obey, sometimes we oversponsor the gospel by overstating the consequences of sin and understating the mercy of God. If we members do not demonstrate God’s unconditional love unambiguously, people will go elsewhere where they find love and acceptance. We simply cannot afford to let people lose sight of God’s mercy, his quickness to forgive, or to suggest that God might love the strictly obedient just a little bit more than the rest of us.

I am afraid we sometimes create the impression that this life is a competition for his love. Maybe it offends us to realize God is no respecter of persons, especially if we have worked hard to live the gospel while others go about their prodigal ways, but the truth is that the sun shines and the rain falls and the flowers bloom for all of us. Every day is an expression of God’s love. Why should we be offended to learn that someone who is not religious felt the innate joy of existence on a hike or at the symphony or that others not of our faith relish and express love of family as well or better than we do? I know in my disobedience I still felt God’s love. Maybe I didn’t call it that, but it was still there in the joy of laughter with friends, in the sounds of seagulls and the smell and sights of a low tide, or in the warmth of a family dinner or a wrestle with my dad. My personal experience with life’s goodness is what drew me back to God.

These experiences of spiritual joy are available to us not because we earned them but simply because we are loved first, because our very existence here is the fruit of his love. God is a spendthrift when it comes to his love. His love is not carefully budgeted. It falls outside of anything we devise to contain it. It is so abundantly available to us, it takes no more than a glance to find it in the most ordinary experiences or the most ordinary objects. As William Blake said, spiritual sight is “To see a World in a Grain of Sand/ And A Heaven in a Wild Flower/ Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/ And Eternity in an Hour.” The men on the road to Emmaus walked on a familiar road and ate in a familiar home, only to discover that their conversation, their meal, and their very existence was permeated by the radiance of the resurrected Lord. With how much more reverence and gratitude would we live if we understood as King Benjamin teaches that God “has created you from the beginning, and is preserving you from day to day, by lending you breath, that ye may live and move and do according to your own will, and even supporting you from one moment to another.” (Mosiah 2:21)?

So obedience certainly isn’t about earning God’s love or approval; it should be an expression of appreciation for your dependency on what King Benjamin calls God’s “goodness and longsuffering towards you.” Once we understand the merciful and personal and utterly unconditional nature of God’s love, obedience ceases to be the old struggle for self-mastery; we feel free to truly love Him as we are loved. What obedience gains us isn’t more love from God, but more power from his love to free us to do the good in the world we were born to do. To become as a child is not to be a child. To act as sheep is not to be sheep. It is to love as Christ loves.

The louder we shout the truths of the gospel and the more frantic and fearful and angry we become at a disobedient world or disobedient children, the less faith and love we seem to have. Don’t let your determination to be obedient cause you to miss the most important and sweet ingredient of life, love. That is not to say that we should stand idle while evil triumphs, but as parents, neighbors, and citizens, we need that quality of Christ’s love that knows both the readiness and boldness of missionary work and the patience and mercy of work for the dead in temples.

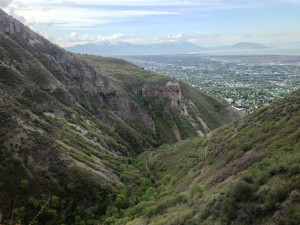

I wish I could say my struggle to be obedient ended at my spiritual birth at age 18. Being a husband and a father and engaging in work and service have shown me enough of my weaknesses for a lifetime to master. Life has tested me, stretched me almost to the point of breaking. As I have grown into adulthood and middle age, I discovered that I simply couldn’t be obedient once and be done with it, or be perfectly obedient ever, or even perfectly desirous to be obedient. When we see despite our best intentions that a trail of our mistakes lies behind us like the black streak of oil behind your car from a leaky oil pan, it is easy to doubt your suitability for the kingdom. It is easy to imagine you are the only one who can’t get it together. In my darkest hours I have felt as broken as I ever was and tempted to just give up. But then something always happens. Maybe something simple, like a beautiful walk up Rock Canyon when the light on the craggy peaks takes my breath away or a performance of Mahler’s Second Symphony that leaves me weeping and unable to speak or a conversation with a friend that lifts my heart or a loving note from a child. Or maybe it is something more directly spiritual, like the time I sat in the celestial room and felt the presence of my deceased brother by my side. The way these experiences have punctuated my life so consistently has finally taught me that obedience is a means and not an end. My striving is not to be perfectly obedient but to love the Lord with all of my heart, might, mind and strength. I have been a lot happier, a lot more free to obey, and a lot more quick to repent when I remember that even though I will never earn God’s love, I will also never lose it. Nothing, absolutely nothing can “separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus, our Lord”(Romans 8:39). Knowing that helps me to look upon my life with compassion, gratitude, humor, and joy, warts and all. When I was younger I imagined the presence of the Savior as an exceptional event I would likely never experience in this life. And probably one that would cause me to shrink. I no longer feel this way, but not because I am more obedient but because I know his love is real and because I love him more. In my home, at work, and at church, when two or three have been gathered in his name, there he has been also. And in the outdoors I can attest that he is, indeed, in the light of the stars and the moon and the bright sun of noonday and is the light which quickens yours and my understanding (see D&C 88). When we know and accept his love, suddenly his presence is ubiquitous and doesn’t cause us to shrink but to expand, like a budding flower in springtime reaching up to the generous sun.

I wish I could say my struggle to be obedient ended at my spiritual birth at age 18. Being a husband and a father and engaging in work and service have shown me enough of my weaknesses for a lifetime to master. Life has tested me, stretched me almost to the point of breaking. As I have grown into adulthood and middle age, I discovered that I simply couldn’t be obedient once and be done with it, or be perfectly obedient ever, or even perfectly desirous to be obedient. When we see despite our best intentions that a trail of our mistakes lies behind us like the black streak of oil behind your car from a leaky oil pan, it is easy to doubt your suitability for the kingdom. It is easy to imagine you are the only one who can’t get it together. In my darkest hours I have felt as broken as I ever was and tempted to just give up. But then something always happens. Maybe something simple, like a beautiful walk up Rock Canyon when the light on the craggy peaks takes my breath away or a performance of Mahler’s Second Symphony that leaves me weeping and unable to speak or a conversation with a friend that lifts my heart or a loving note from a child. Or maybe it is something more directly spiritual, like the time I sat in the celestial room and felt the presence of my deceased brother by my side. The way these experiences have punctuated my life so consistently has finally taught me that obedience is a means and not an end. My striving is not to be perfectly obedient but to love the Lord with all of my heart, might, mind and strength. I have been a lot happier, a lot more free to obey, and a lot more quick to repent when I remember that even though I will never earn God’s love, I will also never lose it. Nothing, absolutely nothing can “separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus, our Lord”(Romans 8:39). Knowing that helps me to look upon my life with compassion, gratitude, humor, and joy, warts and all. When I was younger I imagined the presence of the Savior as an exceptional event I would likely never experience in this life. And probably one that would cause me to shrink. I no longer feel this way, but not because I am more obedient but because I know his love is real and because I love him more. In my home, at work, and at church, when two or three have been gathered in his name, there he has been also. And in the outdoors I can attest that he is, indeed, in the light of the stars and the moon and the bright sun of noonday and is the light which quickens yours and my understanding (see D&C 88). When we know and accept his love, suddenly his presence is ubiquitous and doesn’t cause us to shrink but to expand, like a budding flower in springtime reaching up to the generous sun.

It’s normal to make mistakes and to wish we could do better, but let us not spend time stuck in remorse or regret for our very humanity, for our silly and constant mistakes. It might even help to laugh at ourselves once in a while. Let us look around us, at each other and at this marvelous world, and ask ourselves, in the words of the great poet Mary Oliver: “what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” If we are truly grateful for this precious gift of our life and for the goodness of God and our own nothingness, as King Benjamin calls it, we won’t feel shame but humble gratitude and love for God, for his creations, and for our brothers and sisters. I know of no better motivation to obey God than that.