Romans 5 is an important chapter for Paul’s letter to the Romans, and we will discuss it in relation to Old Testament passages that may have informed it (intertextuality).

Paul essentially proclaims his version of the gospel message in Romans 1–4. Among other things, he features prominently God’s righteousness and being justified by faith in Christ Jesus, more accurately, being “righteoused” by faith (dikaioô + ek + pistis). And starting in Romans 5 the apostle now discusses how believers are to live out this new experience of righteousness/justification by faith. He also highlights reconciliation, being at peace rather than at enmity with God (Rom 5:1–11).

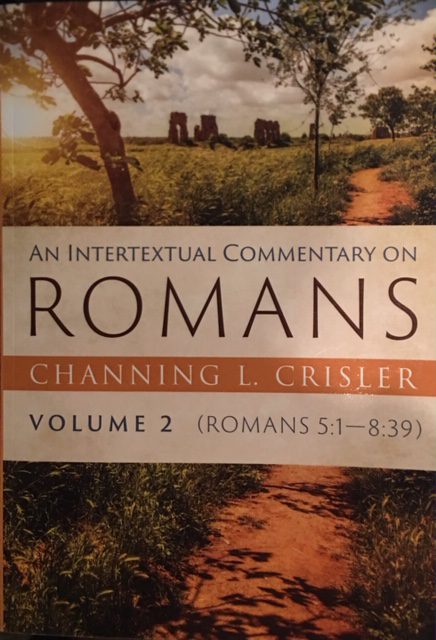

To aid us in this study, I have invited Dr. Channing L. Crisler, Associate Professor of New Testament at Anderson University (South Carolina), to provides us with some of his insights. Dr. Crisler is writing an ongoing multi-volume work, entitled An Intertextual Commentary on Romans (Pickwick Books). Earlier this year we looked at Dr. Crisler’s approach to his first volume, Romans 1:1–4:25

We now begin looking into his second volume, Romans 5:1–8:39.

An Intertextual Refresher

What does it mean to read the Bible intertextually? This refers to the study of text presences in other texts. In relation to biblical studies, it can refer to an interpretative approach for exploring passages of Scripture, such as found in the New Testament (NT), that either quote or allude to something from the Old Testament (OT). The intertextualist specializes in unearthing allusions or “echoes” with the aim of understanding how the pre-text (OT) might be influencing the given text (NT).

When it comes to explicit OT quotes in the NT, intertexualists assume that the quote is only the tip of the iceberg hiding multiple interpretative treasures below the surface. For example, when a NT author quotes from one of the Psalms, sometimes the entire Psalm—or at least a larger portion than what is quoted—is significant for what that NT author is writing. The intertextualist will uncover such things as themes and word parallels from the larger context of that Psalm to show how even the unquoted portion informs what the NT author is writing.

If you want to know more about intertextuality, you can click on my earlier article on my blog, “In Christ,” where I give 5 reasons why we should be reading the Bible intertextually (Click here)

Now onto some questions that I pose for Dr. Crisler regarding salvation terms in Romans 5 and another question on detecting allusions in Scripture:

“Righteoused by Faith” in Romans 5

Oropeza: How do you understand salvation terms in Romans 5 intertextually, in particular, “having been righteoused by faith” (dikaiôthentes ek pisteôs/ δικαιωθέντες ἐκ πίστεως) in Romans 5:1?

Crisler: While these lexemes are not entirely unaffected by a Greco-Roman context, it matters that Israel’s Scriptures function as Paul’s primary and most influential literary source. Multiple pre-texts are evoked in Rom 5:1–11 that should shape our understanding of how Paul understands these lexemes.

First, the phrase δικαιωθέντες ἐκ πίστεως (“having been righteoused by faith”) in Rom 5:1 evokes Genesis 15:6, Habakkuk 2:4, and Psalm 32:1 (31:1 LXX), each of which Paul cites explicitly in the letter prior to this crucial turn in his argument. Therefore, the meaning of “righteousness” and “faith” as Paul perceives it in Rom 5:1–11 is directly informed by these OT pre-texts.

Based on the wider contexts of these pre-texts and Paul’s prior use of them, it follows that faith consists of trust in the prior promise of salvation despite the contradictory and painful appearance of things (notice Rom 5:3–5).

- Abraham in Genesis believed God would give him a son through whom the nations would be blessed with redemption, but he did so while he and his wife were well beyond childbearing years.

- Habakkuk believed in an apocalyptic vision of the nation’s deliverance even while unrighteous Judeans afflicted him and even while he awaited the prospect of judgment at the hands of the Chaldeans.

- David in the Psalm, as Paul identifies him in Rom 4:6, believes that he will receive forgiveness for his own sins even as his own guilt and the activity of enemies challenge that belief.

Moreover, when these three pre-texts are read in concert with one another, a full picture of “righteousness” in its various dimensions also begins to emerge. In short, God’s righteousness is his act of forgiving his people (Ps 32:1) and saving them through his judgment of their enemies (Hab 2:4), according to what he established with Abraham (Gen 15:6).

Paul then takes this prototypical understanding of faith and righteousness and reworks it around the revelation of God’s righteousness in Christ. Despite the painful experiences of believers in Rome, Jews and Gentile alike trust in the Gospel’s promise that God has forgiven them and delivered them from their enemies. This comes through the righteous and merciful judgment levelled against Christ in accordance with what God established with Abraham.

Reconciliation, Peace, and Access

Oropeza: Well said! There are also other salvation-related terms in Rom 5:1–11 beyond being righteoused/justified, such as reconciliation, having peace with God, and having access into grace. Could you comment on these?

Crisler: I suggest that Old Testament pre-texts also shape Paul’s use of lexemes such as “peace” (Rom 5:1), “access” (Rom 5:2), and “reconciliation” (Rom 5:10). For example, the “access” to God provided through Christ echoes Exodus 29:4 and Leviticus 16:6 wherein sacrifices that expiate sin and thereby propitiate divine wrath afford people access to God’s presence, power, and protection. The sacrificial death and resurrection of Jesus provides such access to God for believers in Rome.

Additionally, although reconciliation language is sparse in the LXX, Paul’s use of the lexeme is still intertextually informed when one considers the wider context of Romans 5–8. In this section of the letter, Paul relies heavily on the language and theology of OT lament. This includes his evocation of the figure of a righteous lamenter whose troubles do not signal a lack of peace with God. Rather, they paradoxically indicate peace with God but in the vein of Abraham, Habakkuk, David, and ultimately Christ to whom the Romans are being conformed in suffering (Rom 8:17, 29). It follows that reconciliation with God can look like affliction at his hands.

Oropeza: In addition, I recently wrote an essay in my book, Scripture, Texts, and Tracings in 2 Corinthians and Philippians (Fortress Academic), which posits that Paul’s use of reconciliation originates from Isaiah 9:4 (Septuagint version: LXX). This connection is almost categorically overlooked because the term “reconciliation” (καταλλαγή) appears only in the Greek version of Isaiah (LXX) and not in the Hebrew (Masoretic Text) that is normally used for English Bibles. The verse is also not translated well even in certain English versions of the Septuagint.

The context of this verse in Isaiah is clearly known by Paul, which he refers to in 2 Corinthians 4–5 when discussing reconciliation in light of Christology, the new creation, and his apostolic mission.

Crisler: In my commentary, I suggest further intertextual considerations related to Rom 5:1–11 including Messianic pre-texts (Pss LXX 71[72], 84[85], Isa 32) and pre-texts related to one’s “standing” before God, which implies God’s protection and favorable judgment (Lev 9:5; Ps LXX 23[24]:3–4; 2 Chron 29:11).

When Does an Intertextual Allusion become an Illusion?

Oropeza: Here’s another question; this one more broadly about doing intertextuality in Romans.

The last time I interviewed you, we discussed the phrase “not ashamed of the gospel” from Romans 1:16 (see the interview by clicking here). You said that these words allude to both the Psalms and Isaiah. This raises a question in my mind regarding the validity of having more than one pre-text from the OT behind a given NT text.

This “multiplicity” of text allusions sounds similar to philosopher and literary critic, Julia Kristeva, who originally coined “intertextuality” as a network or mosaic of texts that continues to change as texts collide with other texts (see Exploring Intertextuality, xiv).

But this also raises criticisms regarding this type of intertextual use—we could end up comparing any text with any text by setting aside what the writer might have intended and what the original readers might have understood. I suspect you are not a poststructuralist when it comes to Romans. What, then, do you consider to be prudent boundaries to prevent intertexuality from becoming another form of parallelomania? In other words, how do you interpret Scripture in a way that prevents an allusion from becoming an illusion?

Crisler: Your point is well-taken regarding the way that multiple pre-texts can impact Paul’s thought and language at any given point. Romans 1:16 and Paul’s engagement with “shame–disappointment” (ἐπαισχύνοαμι) language provides a good example of this phenomenon. It evokes several intertextual strands such as Psalms and Isaiah.

How, though, does the analysis not devolve into a kind of poststructuralist reading which the modern originator of intertextuality (intertextualité), Julia Kristeva, encouraged? I suggest that NT interpreters should employ at least three intertextual safeguards that will keep “allusions” from becoming “illusions”:

1. Read to Complement Not Challenge the NT Text

If an interpreter aims to understand a NT writing in relation to its historical and literary context, intertextual analysis of the NT should not aim to produce a reading that challenges the said context. Rather, the analysis should aim to complement the NT text by identifying and assessing the OT language, storylines, and theological strands that inform it.

2. Validate the Intertextual Reading

Richard Hays suggests some well-known tests for intertextual echoes (see Oropeza’s summary of Hays’s criteria here). In addition to those tests, validating a suggested intertextual reading involves determining whether a suggested point of resonance occurs explicitly elsewhere in the NT writing.

For example, if I suggest that Romans 1:16 echoes “shame-disappointment” language from the Psalms and Isaiah, even though Paul does not cite anything from either text in the thesis of his letter, how can I validate my intertextual suggestion?

I examine the wider context of the letter to determine if Paul elaborates on potential disappointment with the gospel. Such elaboration often involves semantic overlap, as it does in this instance. Romans 5:5, 9:33, and 10:11 also refer to potential disappointment with what the gospel promises, including a citation from Isaiah. Therefore, it becomes more likely that OT “shame-disappointment” is echoed in Rom 1:16.

3. Presuppose an Encyclopedic Knowledge of the OT

I presuppose that many scholars simply underestimate the degree to which the OT was both familiar to and formative for NT writers. While their respective audiences could vary in their ability to follow intertextual strands, such limitations (often fretted over in so-called minimalist vs. maximalist debates) simply do not and cannot limit the level of intertextual engagement on the part of NT authors.

In the case of Paul, the interpretive problem is underestimating, not overestimating, the apostle’s scriptural engagement. Historically, it is more responsible to presuppose an encyclopedic knowledge of the OT than it is to limit NT writers’ scriptural engagement.

Oropeza: Thanks, Channing, for all your input! We will be returning to your Romans commentary volumes again soon.