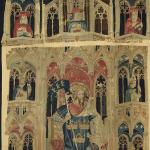

The Tiburtine Sibyl is one of the Sibylline Oracles, prophetic texts from the first few centuries of the common era that were supposedly written by the Sibyls of Greek and Roman mythology. In actual fact they were usually written by partisans of Judaism and Christianity in an attempt to convert Greco-Roman audiences through an appeal to their own antiquity. The Oracle of the Tiburtine Sibyl is one such work, and features the title Sibyl offering a prophecy to a large group of Roman senators about the decline of humanity across nine ages. The Last Emperor material in the text of the Tiburtine Sibyl is an interpolation, meaning that, despite sharing the theme of time lurching inevitably toward its apocalyptic end, it does not represent a part of this original design. As such, it will be considered on its own rather than alongside the whole of the text, as was necessary with Pseudo-Methodius. The Last Emperor passage is short enough to quote in full. According to the Sibyl, a number of very bad things happen to the Roman Empire and its people before a savior emerges:

And then shall arise a King of the Greeks, whose name is Constans, and he himself will be the King of the Romans and of the Greeks. This man will be large in stature, handsome in appearance, luminous in face and also well formed in all the features of his body. And his reign will be limited to 112 years. Therefore in these days there will be much wealth and the earth will give fruit abundantly so that a modius [Roman unit of measurement equivalent to nine liters] of wheat will be sold for one denarius [a small silver Roman coin], a modius of wine for one denarius, a modius of oil for one denarius. And the King will have before his eyes the scripture saying: ‘The King of the Romans shall claim the rulership of the Christians for himself.’ Therefore the islands and cities of the pagans will be laid waste and all the temples of idols destroyed, and all pagans called to baptism and through all the temples the cross of Jesus Christ erected. Then indeed shall Egypt and Ethiopia stretch out their hands toward God. Whosoever does not truly adore the cross of Jesus Christ will be punished with the sword, and when the hundred and twenty years are completed, the Jewish people shall be converted to the Lord, and his sepulcher will be renowned by all. In those days, Judah will be saved and Israel will dwell confidently.

In that time the Prince of Iniquity from the tribe of Dan who is called the Antichrist shall arise. This will be the Son of Perdition and the head of pride, and teacher of errors, the abundance of wickednesses who deceives the world and produces prodigies and great signs through false illusions. But through his magical art he will deceive many, so that fire appears to descend from heaven. And he will shorten the years to months and the months to weeks and the weeks to days, and the hour even to a moment. And from the north shall arise most foul peoples, whom Alexander the King of India enclosed, namely Gog and Magog. These moreover are twelve kingdoms which are as numerous as the sands of the sea.

When the King of the Greeks hears of this however, he shall subdue them with his gathered host and he shall overcome them so thoroughly that it becomes a massacre and after that he will come to Jerusalem and there with the crown from his head and his royal vestments laid down he will relinquish the rulership of the Christians to God the Father and Jesus Christ His Son. And when the Roman Empire shall cease to be, then the Antichrist will be revealed openly and will sit in the house of the Lord in Jerusalem. While he is ruling, however, those two most illustrious men Elijah and Enoch will go forth to announce the advent of the Lord and the Antichrist will kill them, and after three days they will be revived by the Lord. Then there will be a great persecution, like none that was before nor that shall follow after. However the Lord shall shorten those days on account of the elect and the Antichrist will be slain by Michael the Archangel through the strength of the Lord on the Mount of Olives.

(Sibylinnische Texte 185-186)

This, then, is the account we find of the Last World Emperor in the Tiburtine Sibyl. On one hand, we can recognize several elements that were already present in Pseudo-Methodius. There is the same basic plot: the Emperor rises, there is peace and abundance for a time, the enemies of the faith are defeated, Gog and Magog attack and are defeated, and the Emperor relinquishes his crown and kingdom to God, after which there is a very brief account of the end-times that focuses largely on the two witnesses, Elijah and Enoch. There are key elements, like the Emperor’s ceremonial act of giving up his crown, the Antichrist being from the tribe of Dan, and the continual designation of the Emperor as “King of the Greeks” that closely echo Pseudo-Methodius’s account. Pseudo-Methodius’s favorite verse, “Ethiopia shall stretch forth her hands toward God” also appears here, though the Sibyl shows no interest in Pseudo-Methodius’s confused genealogical logic and instead concludes that the phrase indicates the conversion of the (already Christianized) nations of Egypt and Ethiopia. But despite these obvious parallels and marks of influence, the Sibyl’s account is otherwise a very different one from that offered by the Pseudo-Methodian prophet.

For one, there is the Emperor himself. Here, he is given a name, Constans (a Latin term meaning firm, steadfast, or constant and also the name of a few fairly unspectacular Roman Emperors in history) and the perfection of his appearance is dwelt upon at some length. He is also given a set number of years to rule, even if the Sibyl contradicts herself on whether that number shall be 112 or 120. It was true that Pseudo-Methodius gave the Emperor only about twelve years but that was only after the defeat of Gog and Magog; the length of time he reigns before their appearance is left unspecified. Thus, the comparative abundance of personal information makes this Emperor more of a real, distinct individual than Pseudo-Methodius’s anonymous instrument of God, while the superhuman reign of over a century ascribed to him makes the Emperor seem supernatural and even semi-divine.

Then there is the course of his career. The forces of Islam, so prominent in Pseudo-Methodius’s version of the legend, are totally absent. Instead, the Emperor’s initial enemies are nameless pagans. And while the Pseudo-Methodian Emperor was fighting a war of defense against the Caliphate, Constans seems to be the aggressor here, hunting the pagans to their “islands and cities” and burning down their temples. What is more, the peace and prosperity guaranteed by the Emperor’s victory over the Caliphate in Pseudo-Methodius here seems to already be in progress before Constans begins his campaign against the pagans. In short, his enemies here feel like less of an existential threat to Rome or Christianity and more like the remnants of an already overcome paganism that simply need to be mopped up.

It was this aspect of the Sibylline presentation of the Last Emperor’s story—as well as other details such as his having been given a traditional imperial name—that convinced older scholars such as Cohn and Reeves that this version must be earlier than Pseudo-Methodius’s and must date to around the time of the original Greek text’s composition in the late fourth century, despite the fact that the Last Emperor material only appears in a much later Latin translation. To them, the image of a more traditional Roman Emperor battling pagan foes, with no mention of Islam, suggested that this version arose not in the seventh century but during the tumultuous events of the fourth, when a pagan-battling Emperor would have been more welcome. But the lateness of the surviving Sibylline manuscripts with Last Emperor material and a smattering of details that only make sense in a Pseudo-Methodian context (“King of the Greeks,” “Egypt and Ethiopia shall stretch forth their hands toward God”) would suggest that Pseudo-Methodius came first. That being said, the archaic nature of this narrative is still puzzling and has led to some speculation that it may draw from some lost version of the Last Emperor story that predated both it and Pseudo-Methodius.

But, even if its narrative seems less relevant to the concerns of the seventh century and later, the Tiburtine Sibyl does several important things for the Last Emperor myth. For one, by making him a man who hunts down pagans and erects crosses in their temples, the Sibyl makes this Emperor a far more rigid and thorough enforcer of faith that the one in Pseudo-Methodius was. In Pseudo-Methodius, the Emperor was mostly concerned with freeing his people from the Islamic yoke. Though his victory implied the worldwide triumph of Christianity, Pseudo-Methodius did not show him being so proactive as to force widescale conversions. The idea of the Emperor as not only a defender of the faith but an enforcer of it became a key part of his narrative and character, influencing the direction of most later forms of the legend profoundly.

There are several other details of note. The conversion of the Jewish people to Christianity happens at the end of the Emperor’s reign. This does not happen in Pseudo-Methodius. In addition, the lost tribes of Israel return in this version and settle in their old territory—thereby making some sense of Pseudo-Methodius’s ridiculous notion that the Antichrist could be from a lost tribe, that of Dan, and yet still be born and raised in the Galilee. Gog and Magog begin their rampage at the very end of the Emperor’s reign, after the Antichrist has already been born. This is not where the Book of Revelation puts them; there they break out at the very end of time as the Millennium of Christ’s reign on earth concludes (Rev. 20:8-9). But it is a tad closer to where they are supposed to be than in Pseudo-Methodius, and the direct quotation of Revelation 20:8 in the description of Gog and Magog being “as numerous as the sands of the sea” suggests a greater influence from that book. Crucially, the Sibyl also moves the location of the Emperor’s surrender of his crown and title to God from Golgotha to the Mount of Olives, where the Antichrist was popularly expected to meet his demise. All of these details, the conversion of the Jewish people, the return of the lost tribes, the late appearance of Gog and Magog, and the greater importance of the Mount of Olives, are key elements of the standard medieval narrative of the end-times but ones that did not appear or (in the case of Gog and Magog) featured differently in Pseudo-Methodius. By incorporating the more conventional apocalyptic program into the Emperor’s story, the Sibyl makes the Emperor himself a better fit for that apocalyptic narrative as people of the time in Western Europe almost universally understood it.

And the Sibyl’s last major change accomplished something similar but more profound. As noted, the Emperor is a more fleshed out character here than in Pseudo-Methodius. He is also a more impressive figure, who is given both an inhumanly long reign and the personal victory over Gog and Magog that Pseudo-Methodius had denied him. Paul J. Alexander, in his article, “The Diffusion of Byzantine Apocalypses in the Medieval West and the Beginnings of Joachimism” makes the observation that the Sibyl’s narrative “lends the careers of both the Last Emperor and the Antichrist a curious Jesus-like character in that they both belong to history and to eschatology. The Last Emperor is a human being born in time but he seems to survive into the final conflict of God and Antichrist” (“Diffusion” 59). This is true as far as it goes. The Emperor does have some qualities that make him seem godlike, chiefly his incredibly long reign. And by moving his battle with Gog and Magog into the time of the Antichrist, the Sibyl allows the Emperor to participate in the apocalyptic narrative proper, the part we find in Revelation, even if only in a glancing way. But, in other ways, the Emperor Constans of the Sibyl seems more human and less divine than his Pseudo-Methodian counterpart.

There are no Biblical verses applied to him that had originally been applied only to God the Father or Christ. The sense that he is directly guided by God’s will at every turn is absent; instead, this Emperor decides on his course of action by consulting scripture, like any good Christian. And when it comes time to surrender his crown and throne, the Sibyl makes clear that it is “to God the Father and Jesus Christ His Son” that he does so. Pseudo-Methodius had left Jesus out of that equation entirely, even applying a Biblical verse in such a manner as to suggest that the Emperor, not Jesus, was the “Son of God.” The author of the Tiburtine Sibyl makes no such mistake. The lordship and uniqueness of Jesus as Christ are emphasized, while the Emperor is obviously subject to both Christ and the Father. The Emperor is still a messiah of sorts but he is no longer on the same level of the Messiah, who is Jesus Christ. This serves to make the Emperor much more palatable as a participant in the apocalyptic narrative for medieval Christians. No matter how superhuman he might appear, he is ultimately simply another human follower of Christ who just so happens to have been chosen for a great purpose. And in a time of kings and emperors, it did not seem far-fetched that a great but utterly human emperor could play such a role when the end of days finally rolled around.

Thus, in her presentation of the Last Emperor, the Sibyl jettisons all the potential blasphemies that had surrounded the figure in Pseudo-Methodius’s telling. No longer is there the dangerous equivalence between the Emperor and Christ, no longer the gnomic hints of the Emperor’s own divinity. This is an Emperor much more fit for orthodoxy than his counterpart. He is also more fit for the apocalyptic narrative as medieval people would have known it, with several details of his story now matching up to what were then the accepted truths about the apocalyptic age. Alexander may be right to suggest in “The Last Roman Emperor and Its Messianic Origin” that “even if the Latin Sibyl preserves an earlier form of the Legend, it was the Pseudo-Methodian version, with its emphasis on the Emperor as the conqueror of Islam, that captured the imagination and kindled hopes in the Byzantine Empire, in Western Europe and in Slavic lands” (“Last Roman Emperor” 15). But while the Emperor’s role as opponent of Islam remained important and helps to explain the idea’s longevity, the Sibyl did contribute two things of lasting value to the myth. One was to find place for the Emperor in traditional Christian theology and eschatology. The other was to make the Emperor the enforcer of faith in the Empire as well as the conqueror of Christianity’s enemies. This later notion would only grow more important over time, so that by the later Middle Ages, it had morphed into the belief expressed by Savonarola and others that the Emperor would be a chastiser and purifier of the Church itself.

Developments continued in the legend after Pseudo-Methodius and the Sibyl, as well. In the tenth century, Adso of Montier-en-Der, while giving the medieval West its authoritative version of the Antichrist legend in his Letter on the Origin and Time of the Antichrist, would assure his patron:

Since therefore the Apostle Paul said that the Antichrist would not come before, unless the departure will come first, that is to say, unless all realms will first depart from the Roman Empire, to which they had previously been subdued. However this time has not yet come, because, while it is true that we may see the Roman realm for the most part destroyed, nevertheless, as long as the Kings of the Franks endure, who hold by right the Roman Empire, the dignity of the Roman realm will not perish everywhere, because it will continue on in its kings. Some of our scholars truly state that one of the kings of the Franks shall possess the entirety of the Roman Empire, which shall in newest days. And he shall be the greatest and last of all kings. After he has governed the kingdom happily, in the end he shall come to Jerusalem and on the Mount of Olivet he shall lay down his scepter and his crown. This is the end and consummation of the Roman and Christian empire. (Sibylinnische Texte 110).

This brief account of the Emperor in his treatise on the Antichrist proved surprisingly decisive. Because his work became the definitive account of the Son of Perdition for centuries, Adso helped to spread and legitimize the Last Emperor myth in Western Christendom. His text also emphasized the Emperor’s success as an administrator and confirmed the Sibyl’s change of location for his surrender of power from Golgotha to the Mount of Olives. But most importantly, he made the Last Emperor a “King of the Franks.” This association of the Last Emperor with the Frankish kingdom would be inherited by its successor-states, the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire; until the end of the Middle Ages most Last Emperor claims would be made on behalf of either or both of these powers.

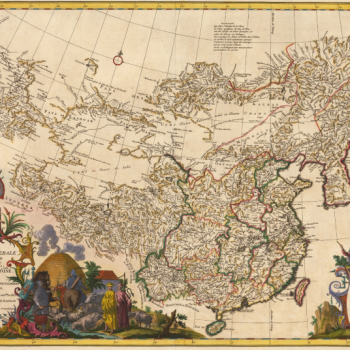

Its reach was vast and claimants by no means had to be French or German. Indeed, the notion of a Last World Emperor and his advent lurks behind some of the defining events of the Middle Ages. We have already looked at the formation and continuance—in name if not always in fact—of the Holy Roman Empire, but there are plenty of other traces. Crusaders looked to the legend to justify their attempts to take the Holy Land and the bloody deeds against the peoples who dwelt there. Increasingly, however, the Emperor came to be seen as a chastiser of the Church who would destroy all corrupt priests and restore the faith to its original purity. Holy Roman Emperors used this form of the idea as propaganda in their frequent battles with the Papacy for control of Western Christendom, as did French kings like Charles VIII. So too did would-be religious revolutionaries like Cola di Rienzo and Savonarola. Even Dante got in on the act. Dante’s own prophecies of the coming Last Emperor are littered throughout his greatest work, the Divine Comedy. The future Emperor is referred to as the “Greyhound” at the beginning of Inferno (Inferno I.101) and assigned the number DXV (515) as a holy counterpart to the Antichrist’s number 666/616 in Purgatorio (Purgatorio XXXIII.43). Finally, in Paradiso, Dante unfolds a grand vision of a Roman Empire destined to rule the world until the end of time (Paradiso VI), with the Roman imperial eagle enshrined in Heaven itself as the symbol of justice (Paradiso XVIII-XX). Dante even penned a political treatise entitled De Monarchia, in which he carefully laid out a number of socio-political, historical, and logical arguments for why the Last Emperor should rule the world. In doing so, the great poet became perhaps the only person to ever summon rational and sober political theory to the aid of apocalyptic prophecy. Only Joachim of Fiore made a solitary stand against the notion of a final imperial monarch when he replaced the Last Emperor with a reforming Angelic Pope in his apocalyptic system. But this led to quite a different result than he had intended. The Angelic Pope became a popular figure alongside the Emperor, leading to a period of time when Catholic Europe, like the ancient Essenes, expected the advent of three separate messianic figures.

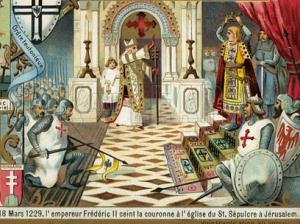

Prophets, divines, and wise men debated whether the remarkable Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (1194-1250) was the Last Emperor or the Antichrist, speculation which his death did little to dispel. A few centuries later, the same dueling identifications would envelop Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain (1500-1558). Between being the last Holy Roman Emperor to receive a coronation, ruling the world-spanning Habsburg Empire, encouraging the forcible conversion of the Americas to Christianity, and abdicating his throne to retire to a monastery a few years prior to his death, Charles V probably came the closest of any historical person to fulfilling the Last Emperor’s eschatological program. But at his death, Antichrist failed to appear, and speculation moved on to new targets. However, his reign was not the first time that the Last Emperor legend had reached its ghostly fingers into the European colonization of the Americas. Indeed, the colonization might never have begun without it; Christopher Columbus, fervent believer in prophecy that he was, fully expected that his opening of a sea route to “the Indies” would be only the first in a sequence of events that would culminate in King Ferdinand striding victoriously into a recaptured Jerusalem as the Last World Emperor.

The myth has resurfaced from time to time in the modern age; the crown of the Holy Roman Empire remains on display at the Hofburg in Vienna only “until there is again a Holy Roman Emperor” (“The Imperial Crown”) and Frank Kermode discovered a book written by a “Fr. Cyril Marystone” in 1963 which promised that “[t]he Great Monarch will come in 1966, and in consort with the Great Pope will achieve world victory, the reform of the Church, the conversion of the separated, and a universal Holy Roman Empire” (Kermode 15). But it is undeniable that the myth had its heyday in the Middle Ages. Once modernity advanced too far and brought with it the time of revolutions and the fall of monarchies, the hope of a world-redeeming savior emperor began to falter in popularity. But this came after it had already been an accepted part of the Christian end-times scheme for over a thousand years. Its development during that period demonstrates the extreme creativity and versatility that medieval thought and prophecy displayed, even as these narratives’ excitement about the slaughter of non-Christians should give us pause. And its very existence and wide sphere of influence demonstrates that, for most of the faith’s history, Christians had no difficulties imagining that Jesus of Nazareth might not be the only messiah of the end-times.

But through all of his manifold transformations, and despite the best efforts of works like the Tiburtine Sibyl, the Last Emperor never quite lost his supernatural and semi-divine quality. This is evidenced by one of the strangest outgrowths of the Last Emperor’s legend, namely, the belief that it would be a dead or “sleeping” king that would return to fulfill the role. The idea was probably sparked by the remark in Pseudo-Methodius that the Emperor is “he whom men have supposed dead,” but it took a form that went far beyond that text. Marjorie Reeves, in Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages, notes that “under the year 1095 Ekkehard of Aura recorded the circulation of a fabulosam confictum concerning the resurrection of Charlemagne, who would once more lead the Christian in triumph against the infidel and bring in the era of peace and prosperity” (Reeves 301). Norman Cohn remarks, in The Pursuit of the Millennium, that at the time of the First Crusade, “it was also widely believed that Charlemagne had never died at all but was only sleeping, either in his vault at Aachen or inside some mountain, until the hour came for him to return to the world of men” (Cohn 55). The prophetic revival that spread throughout Europe in the wake of Joachim’s writings only strengthened the connection between Charlemagne and the Last Emperor. It would also introduce new candidates for the role among other departed monarchs, such as Frederick Barbarossa, Frederick II, the last Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI, and the Portuguese King Sebastian, all of whom owed their supposed survival and future return to their imagined role as the Last World Emperor.

Most of these legends of royal undeath survived into modern times and thus became the most lasting legacy of the Last Emperor myth. Many have now encountered the myth of the “sleeping king” in various forms without ever realizing that it arose out of the eager expectation of a world-conquering, redemptive monarch in the Middle Ages. That being said, as most of these figures fade further into the depths of the past and their lives become matters of scholarly study rather than folklore, the myths of their return have largely been reduced to historical curiosities, found only as footnotes in biographies or in collections of old fairy tales. There is, however, one royal figure whose story is still bound up inextricably with the notion of a future return and who still has enough mystery and uncertainty surrounding him to make the idea stick. That figure, of course, is Arthur. We shall consider his relation to the Last Emperor myth and the role envisioned for him as Christianity’s second messiah in our next entry.

A Note on Sources

For the text of the Oracle of the Tiburtine Sibyl and Adso’s Letter on the Origin and Time of the Antichrist, I have relied upon the standard Latin texts published by Ernst Sackur as part of his Sibyllinische Texte und Forschungen (Halle: Max Niemeyer 1898). An online copy of this work can be found at Hathi Trust: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.16188553. The translation from the Latin is mine.

Other texts cited are:

Alexander, Paul J. “The Last Roman Emperor and Its Messianic Origin.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtlauld Institutes, vol. 41 (1978): pp. 1-15. [An online edition of this paper can be found at https://www.jstor.org/stable/750860.] and “The Diffusion of Byzantine Apocalypses in the Medieval West and the Beginnings of Joachimism.” Prophecy and Millenarianism: Essays in Honor of Marjorie Reeves, edited by Ann Williams. Harlow: Longman, 1980. 53-106.

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy, translated by C. H. Sisson. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Cohn, Norman. The Pursuit of the Millennium. London: Secker and Warburg, 1957.

“Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire.” Holy Roman Empire Association. Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire (holyromanempireassociation.com)

Kermode, Frank. The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction, 1967. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Reeves, Marjorie: Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages: A Study in Joachimism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

The Revelation of John. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. 1556-1575.