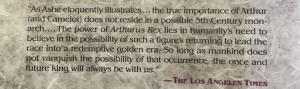

Among the various Arthurian texts in my possession is a 1987 edition of Geoffrey Ashe’s The Discovery of King Arthur, a seminal book in which Ashe (who passed away early last year) advanced his argument that the historical Arthur was a fifth-century king known as Riothamus. The back cover of the 1987 edition includes an excerpt from a Los Angeles Times review that I had always found rather curious. It reads:

As Ashe eloquently illustrates…the true importance of Arthur (and Camelot) does not reside in a possible 5th Century monarch….The power of Arthurus Rex lies in humanity’s need to believe in the possibility of such a figure’s returning to lead the race into a redemptive golden era. So long as mankind does not vanquish the possibility of that occurrence, the one and future king will always be with us.” (qtd. in Ashe, back cover)

While Ashe certainly does offer a number of insightful remarks regarding the return legend, he does not speak of it as an actual possibility. And the book is entirely premised upon the existence of a “possible 5th Century monarch” that the review seems so dismissive of. Why, I have often wondered, did the reviewer make these comments, when they are at such variance from the actual subject matter of the book? And perhaps more importantly, why did the publisher choose to give them pride of place on the back cover, when surely another, more suitable comment or review—like the one from The Atlantic that graces the front cover—could have been chosen instead?

I think that the note I ended on last time might get us closer to the answer. I have never seen the full review, but the excerpt quoted on the back cover of Ashe’s book makes no comparison of Arthur with Christ. And yet, the character it ascribes to Arthur’s return is decidedly millennial. Here, Arthur once again takes on Christ’s role as redeemer and savior, literally guiding humanity into “a redemptive golden era.” It is assumed that there will not only be prosperity but a kind of spiritual salvation as well. Importantly, this prosperity and this salvation are global; Arthur’s saving mission is explicitly applied to all of humanity, rather than simply to Britain itself or countries with British heritage. We have a term for when these particular attributes—the future golden age, the redemption of the world, and a universal reach that extends to all humanity—are combined into a single vision: millennialism.

This reviewer may not be knowingly invoking either the Jewish Messianic Age or the Christian Millennium—although, given that it lies behind every similar idea the West has come up with since becoming Christian, its fingerprints are certainly there. Regardless, the review is professing a millennialist understanding of what Arthur’s return will entail, even though Ashe himself is far more circumspect and prefers to focus on the return myth’s nationalist associations. This long series has shown that the Christian concept of the Millennium is the source of the return myth’s own utopian associations. This review of Ashe’s book demonstrates that the influence of the Millennium idea is still very much present in modern conceptions of the return myth, even if the explicitly Christian elements have largely disappeared. It is certainly a testament to the continuing appeal of the promise of the Millennium that only a few decades ago a reviewer in a respected publication could express ideas about Arthur that, while not explicitly Christian, are deeply and incontrovertibly millenarian.

It appears the reviewer was moved to make these statements by Ashe’s basic contention that was a real King Arthur who can be identified with a figure of the fifth century. Even though Ashe does not trade in millennialist ideas within in The Discovery’s pages, simply asserting the reality of Arthur’s existence was enough to once again stir the millennialist hopes inherent in the idea of the Once and Future King. It makes one think about how the question of Arthur’s existence remains at the forefront of public interest today. Scholars and academics may consider that question below their notice and prefer to study the nuances of the Arthurian story as a story. But the public today shows little interest in the Arthurian story itself. While Arthurian elements continue to recur in popular culture, not since John Boorman’s Excalibur in 1981 (or perhaps Monty Python and the Holy Grail in 1975) has an Arthurian text or film enjoyed truly mainstream popularity. And yet, the public is deeply invested in the real existence of King Arthur. The only question I am ever asked when I tell people outside of academia that I am an Arthurianist is, “Was he real?” Invariably, the person asking it does so in such a manner as to indicate what answer they are looking for: a “Yes.” Why should the existence of a fifth-century leader of people ancestral to the Welsh and Cornish be so important to so many people, when precious little else of the Arthurian tradition is? Could it be that, as with the reviewer of Ashe’s book, the reality of Arthur’s past existence allows at least some of them to have hope, however unrecognized, in the millennialist promise of his future return?

I cannot answer that question with anything more than speculation. But I think that I have shown, over the course of this series, that the idea of the return is rooted in just this kind of millennialist hope. I have been criticized and insulted by academics before—in language unbefitting the supposed high-mindedness of profession—for suggesting that belief in the return is rooted in hope and that it transforms Arthur into a figure of hope. I have been told that doing so dilutes the tragedy at the heart of Malory and other Arthurian writers. Scholars are certainly attached to that sense of tragedy. I think one of the reasons Bridges and Ticknor have been neglected or ignored in most studies of American Arthurian literature is because scholars, the Lupacks included, prefer to focus on the playing up of Arthurian tragedy and mockery of Arthurian ideals themselves in American literature. Bridges and Ticknor, in their celebration of Arthurian hope, went completely against that grain, and thus have been ignored even by academics who specialize in both American and Arthurian literature.

Perhaps I—in writing things like this series—have also diluted the tragedy of Arthur’s story somewhat. But I am only following my sources; human beings on the whole have never been particularly good at tolerating unmitigated tragedy. Something within drives us to transform it into hope. In some sense, this makes the tendency of authors to link Arthur and Christ more understandable. For Christians themselves transform tragedy into hope every time they affirm that the tragedy of Christ’s crucifixion was followed by the triumph of his resurrection and the hope of his Second Coming. So too have Arthur’s devotees across time transformed the tragedy of his downfall into hope for a future reign, one that has itself only grown more final and transformative over the centuries.

Of course, not all hopes are justified. Tennyson’s hope that his “crown’d Republic’s crowning common-sense, / That saved her many times, not fail” (“To the Queen” ll. 61-62) and that the British Empire would forever avoid a reckoning akin to “[t]he darkness of that battle in the West, / Where all of high and holy dies away” proved futile. So too did the hope of Bridges and Ticknor that Arthur’s return and the subsequent birth of the millennial kingdom would put an end to the strife of the Civil War. If Arthur truly was looking on from Avalon, weighing up which side to intervene on, he apparently decided to sit the conflict out. The Union did not need him and no savior came to revive the Confederacy, no matter how much its pernicious legacy lives on in America’s current political discourse.

Christians are also no stranger to this sense of disappointment; the earliest Christians believed that the Second Coming would happen within their own lifetimes or soon after. Countless believers through the centuries have convinced themselves that they know the exact time of Christ’s return. Inevitably, these expectations also came to nothing and. After two thousand years, Christians still wait patiently for the fulfillment of the greatest of God’s promises. Still, the hope lives on, daunted by time, but not vanquished. In both Christ’s and Arthur’s cases, the failure of specific expectations has traditionally done little to dampen the overall appeal of the millennialist hope. Both return narratives continued to occasion healthy amounts of public interest well past the end of the twentieth century.

Whether they shall outlive the current century, or the centuries to come, is another matter. Christianity is in sharp decline in most Western nations. People there, it seems, have finally grown tired of waiting for the promised return, the Millennium, and the “new heavens and new earth.” It remains strong outside the West and is even growing in China, which optimistic forecasts have suggested may be the world’s largest Christian nation by 2100. Yet, within the West itself, the current sentiment is one of inevitable and irreversible decline. As to whether it is an accurate sentiment or a misguided one, only time will tell. Meanwhile, the Arthurian tradition is itself in a period of public neglect. As I noted above, it still has a firm presence in popular culture, but it is rare for any new text or film about Arthur to generate much mainstream interest. This is a far cry from the Victorian era, a little over a hundred years ago, when the Arthurian story functioned as a kind of foundational myth for the English-speaking world. Of course, this current lull does not have to be permanent. The Arthurian story previously fell almost completely out of fashion in the eighteenth century before making a stunning comeback in the nineteenth. This was due, in large part, to Tennyson’s harnessing of the millennialist energies inherent in the myth of Arthur’s return.

Such energies may revive the Arthurian tradition again. Or Christianity’s own millennialist energies might give it the boost it needs to survive in the world of today. Or they may lead to new and innovative spiritual formulations like those advanced by Bridges and Ticknor over a century and a half ago. That is not to say that the composite Christ-Arthur figure is primed for a comeback. But millennialist impulses do have a tendency to develop in strange directions. It is not unthinkable that new divine characters, equally unorthodox but more adapted to a contemporary audience, could emerge from today’s newly developing spiritualities or that old sources of faith and hope might be revived in surprising new ways. If nothing else, the long history of Arthur as the other Christ demonstrates that millennial hopes, dreams, and impulses inevitably survive, endure, and transform the more traditional narratives that surround them. Whatever the future fate of Arthurianism and of Christianity, there is no reason to think that these same millennialist impulses will not exercise their transformative powers again, though perhaps in different forms than those we currently know. For all his wrong-headedness, Ticknor was right about one thing: millennialist hopes never truly die. There will always be someone willing, in Sallie Bridges’s words, to place themselves “mid the throng that wait the coming King.”

Works Cited

Tennyson, Alfred, Lord. Idylls of the King. Edited by J. M. Gray. London: Penguin Books, 1983.

Ashe, Geoffrey. The Discovery of King Arthur. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1985. Owl Press Books, 1987.