While the nation as a whole at the outbreak of the Civil War was experiencing a vogue for a romanticized British past of wise kings, gallant knights, and courtly damsels, this fascination was particularly strong in the Southern states. Southerners had a marked tendency to develop fixations on symbols of heroic British knighthood and apply those symbols to themselves. Jason Philips, in Looming Civil War, describes their particular fascination for Henry “Hotspur” Percy, the fifteenth-century English rebel leader immortalized in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1:

Nineteenth-century Americans considered Hotspur a tragic hero, a daring nobleman who died avenging his insulted honor on the field of battle. A military hero from the countryside, Hotspur represented to southern slave owners the older feudal order that rebelled against the king’s more modern style of rule that courted the masses. (Philips 119)

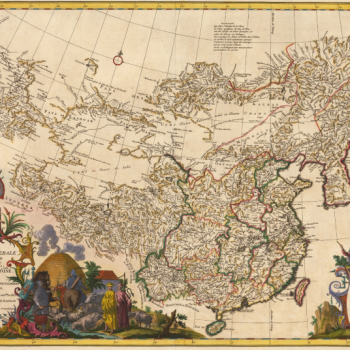

Yet, it was not only Hotspur that captured the Southern imagination. John H. Matsui, in Millenarian Dreams and Racial Nightmares: The American Civil War as an Apocalyptic Conflict, notes that “Southerners could hardly resist romanticizing their generals as latter-day cavaliers in the mold of Prince Rupert, if not an even more storied knightliness akin to King Arthur’s Camelot” (Matsui 22). Figures such as Hotspur, Prince Rupert (who fought for King Charles I in the English Civil War), and the Knights of the Round Table were seen by Southerners as the last defenders of a bygone social order where everyone and everything was fitted into its proper place. Sitting at the top of the brutally hierarchical social pyramid that was antebellum Southern society, the planter aristocracy considered themselves to be the heirs of that social order and hence a kind of knightly brotherhood. Thus arose the paradoxical situation in which one of the most unjust and inhumane social orders the world has ever seen preoccupied itself with the “chivalric” virtues of honor, courage, and gentility. The illusion of Southern chivalry justified a socio-economic system of subjugation and slavery by making it seem as though that system had been passed down from a sacrosanct age of heroic knighthood.

An illusion it was, but without doubt a powerful one. Even today, it is the root of the “Lost Cause” myth, the pernicious belief that the Confederacy, in the mode of Hotspur and Prince Rupert, heroically held out to the end, losing due to unbeatable odds and dishonorable foes rather than because it was outfought by the likes of Grant and Sherman and weakened by its own overreliance on slavery. But the illusion was even more powerful during the time of Civil War, when the soldiers in the field were being painted by mythmakers back home as knights in armor fighting bravely against the fiends of the federal army. And of those mythmakers, few were as ardent or as certain of their beliefs as was Francis Orray Ticknor.

A physician from Georgia who practiced poetry on the side, Ticknor, like Sallie Bridges, failed to achieve much notoriety before his death in 1874 and today languishes beside her in obscurity. But unlike her, he did manage to find some fame after death, enjoying something of a renaissance in the first half of the twentieth century. In part, this was because his wartime poetry, which invariably portrayed Confederate soldiers as heroic modern-day knights-errant, perfectly suited the newly-ascendant “Lost Cause” myth. But Ticknor also benefited from having left behind a family that was determined to promote and safeguard his legacy by cultivating the leading literary figures of the South in his name.

A record of their progress can be found in the magazines and journals of the time. An early product of their efforts was S. A. Link’s article entitled “Dr. Frank O. Ticknor.: ‘The Lyric Poet of the South’” (later included in his book, Pioneers of Southern Literature) that appeared in The Independent of June 6th, 1889. Here, Link lamented, “yet the name of Dr. Frank O. Ticknor does not appear as a diminutive ‘fixed star’ in the ‘poetical firmament’” (Link 5) of the South and sought to correct this with a highly positive appraisal. Link remarks several times on later developments in the Ticknor family and cites them as sources of information—such as when he remarks that the 1879 first publication of Ticknor’s work “omitted many of what the family consider the best poems” (6)—indicating that they were the driving force behind the article itself.

Similarly, a piece entitled “Dr. Francis O. Ticknor” from ten years later cites “Mrs. Rosa N. Ticknor, of Columbus, GA” and a “Mr. Henry Ticknor” as its among its sources (I. M. P. O. 176). Rosa Nelson Ticknor was the widow of the poet and is the article’s chief source; the piece largely consists of her reminiscences punctuated by quotations of Ticknor’s poetry. No other source but her is quoted directly, though a further unnamed “member of the family” (Henry perhaps?) is cited for details on Ticknor’s death (174). From texts such as these, a recognizable pattern emerges. Wherever one finds a positive mention of Ticknor in these years, one inevitably discovers the Ticknor family behind it. And wherever the Ticknors’ campaign takes them, their formidable matriarch, Rosa Ticknor, can usually be found pulling the strings.

It was primarily Rosa’s determination and tenacity that fueled the family campaign to promulgate her husband’s memory. But, as Link’s article makes clear, her efforts and that of the family as a whole bore little fruit in the nineteenth century; Link himself notes how obscure Ticknor was in his time. Things would turn around, however, in the first decades of the twentieth century. An important milestone was reached in 1907 when Ticknor was given an honored place in the Library of Southern Literature, a massive volume edited by Charles W. Kent, Edwin Anderson Alderman, and Joel Chandler Harris. This work, as its name and length both suggest, attempted to define a canon of Southern literature. The inclusion of Ticknor’s poems alongside a lengthy biographical sketch secured his ascension into that canon. This biographical sketch by Charles Alphonso Smith is both a testament to the fact that Ticknor’s rise to prominence only came about in the 1900s, for “it is only in very recent years that his recognition may be said to have become in any sense national” (Smith 5353) and of the central role that Rosa herself played in winning that recognition for her husband. The latter point is demonstrated by the fawning and obsequious address that Smith makes to her directly, “Mrs. Ticknor still survives her gifted husband, and the author of this sketch would like to assure her that … her unshaken confidence in the triumph of his name and fame have already been vindicated by the verdict of the years and have themselves become a part of the history of Southern literature” (5354).

Smith also mentions that “Miss Michelle Cutliff Ticknor … a granddaughter of the poet, will probably edit an enlarged edition” (Smith 5358). Spurred both by the fact that the first edition had quickly gone out of print after its 1879 publication—Link, ten years after that publication, was already complaining, “unfortunately his poems have gone out of print” (Link 6)—and by the family’s distaste for that original volume, Michelle Cutliff Ticknor edited a second, expanded, and definitive edition and published it in 1911. Immediately afterward, Ticknor’s poems began appearing in anthologies of Southern literature such as Walter Neale’s 1912 Masterpieces of the Southern Poets and Charles W. Kent’s own Southern Poems of 1913, with Cutliff Ticknor’s edition invariably cited as the source. Thus, the publication of the second edition of Ticknor’s poems represented the culmination of the long effort spearheaded by Rosa to enshrine him in the Southern literary canon. It had taken about forty years for her and the family to achieve that goal. Their success would last for another fifty years until literary tastes began to change and Ticknor’s saccharine Confederate nationalism fell once more out of fashion.

In truth, despite the insistence of Ticknor’s family and their literary supporters, there was never very much to recommend his poetry. Compared to Bridges, he may have enjoyed the greater literary legacy, but Bridges was—for all her own faults—the better versifier. Ticknor’s poems are staid and repetitive and paint the Confederacy in an invariably sentimentalist and romantic light. Indeed, the scholarly claim that Southerners saw their soldiers as heroes out of a British feudal past finds an almost comically literal confirmation in Ticknor’s wartime poetry. There, in poem after poem with mind-numbing regularity, Ticknor celebrates the Confederate military as recapturing the spirit, and even reembodying the personas, of the great knights of medieval Britain. His war poems could serve as a test case for Mircea Eliade’s famous concept of repetition, given how often Ticknor describes Confederate soldiers as though they themselves are those earlier heroes, come to life again. It is as though, in Ticknor’s view, the whole pantheon of knightly heroes had been physically reincarnated in the Confederacy. And of that pantheon, no hero sat higher in his mind than King Arthur.

Arthurian allusions crop up frequently in Ticknor’s poetry. For instance, a poem entitled The Gap” commemorates D. H. Hill’s defense of Boonsboro Gap by proclaiming, “Here wrestled Arthur and his knights!” (“The Gap” l. 8), thereby explicitly identifying Hill and his forces with King Arthur and the heroes of the Round Table. Another poem, “The Sword and the Sea,” compares the CSS Alabama to Excalibur, “that great glaive that Arthur gave / In guerdon to the sea” (“The Sword and the Sea” ll. 25-26). Meanwhile, his most famous poem, “Little Giffen” tells of how Ticknor personally nursed a sixteen-year-old Confederate soldier back to health, only for that soldier to return to battle and presumably perish. The poem ends not with Giffen’s vanishing, but with Ticknor proudly proclaiming that “were I king / Of the princely knights of the Golden Ring” (“Little Giffen” ll. 32-33), he would still prefer Giffen’s chivalrous example over theirs. Given Ticknor’s affiliation with the Confederacy, this last line quite possibly refers to the pro-Confederate secret society known as the Knights of the Golden Circle. But it also seems to harken back to King Arthur and the Round Table, as demonstrated by the fact that Charles Kent, in his own 1913 edition of the poem, amends the line to the more explicit “Of the courtly Knights of Arthur’s ring” (Kent 33).

Ticknor’s statement that “I sometimes fancy that were I king / Of the princely knights of the Golden Ring” (or “the courtly Knights of Arthur’s ring”) is certainly striking. It indicates that Ticknor was in the habit of imagining himself as King Arthur in a bit of poetic grandiosity comparable in its way to Sallie Bridges’s casting herself as the catalyst of Arthur’s return. But it is fully in keeping with his tendency to see the Confederacy as equivalent to, and a kind of reincarnation of, Arthur’s Camelot. Given this, it is perhaps not surprising that the course of the Civil War would lead him, as it did Bridges, to ponder the possibility of Arthur’s return. After all, Ticknor had, in some sense, been thinking about the return of dead heroes for a while. While he may not have pondered it as a fantastic possibility in the way Bridges had at the war’s beginning, Ticknor had long been playing with the idea that dead knights lived again in the person of Confederate soldiers. Thus, like Bridges, all he needed to actually start thinking about the physical return of a dead knightly hero was a crisis of faith in the ability of his chosen cause to prevail.

In Ticknor’s case, it was not the near-failure of the Union, but the actual failure of the Confederacy—its fall to the armies of Grant and Sherman in 1865—that caused him to make the leap and decide that King Arthur’s return was the only hope for national salvation. What is surprising, however, is that Ticknor not only came upon the same basic idea as Bridges had a few years before, apparently independently, but that he also formulated it in the same rather blasphemous terms. For, like Bridges, Ticknor nor only expects Arthur to intervene in the chaos of the Civil War, but he also identifies a returned Arthur with Christ and sees the King’s future return as the beginning of God’s millennial reign on earth.

This is all the more remarkable given that Ticknor, unlike Bridges, did not seem particularly vested in American nationalist millennialism until the Confederacy’s collapse. He did play with the idea occasionally. His 1854 poem, “The Conquest of Labor”, for instance, he dares to hope that the fruits of American industry “[s]hall circle the earth with their mission sublime, | Till the world that was fair in the morning of Eden | Shall blossom again in the sunset of Time” (“The Conquest of Labor” ll. 21-24). Yet it seemed then like something he only used out of convention; he never appeared very passionate about it. However, millennialist nationalism was still very much a part of the cultural framework of his time and he clearly absorbed its main message, however passively. In addition, similarly to Bridges, he was devoutly religious, as many of his poets testify. Like her, his religious leanings appear to have been quite conventional. Yet, also like her, they could apparently take him down quite blasphemous paths when faced with the existential crisis of apparent national defeat. Thus, when the South’s defeat awakened the need in Ticknor for a new type of American millennialism, one that saw God’s coming kingdom embodied not in America as a whole but in the vanquished Confederacy, the necessary ingredients were already all there for his use.

Of course, the Confederacy’s defeat was something of an obstacle for Ticknor in his effort to identify it with God’s triumphant future kingdom. Ticknor got around this through a very literal application of that Neo-Confederate battle-cry, “The South will rise again.” Drawing on Christ’s leading role in the coming of the millennial kingdom, Ticknor chose to equate the South with Christ, specifically with the crucified Christ of the Gospels. Just as that Christ had risen from the dead to signal the eventual coming of his future reign, he claimed that the Confederacy itself would rise from the ashes upon Christ’s Second Coming. Allusions to this idea appear in his later poetry; a poem entitled, “Under the Willows,” for instance, warns the victorious Union that, “The volume closed not with an Abel smitten, or with a Christ crucified” (“Under the Willows” ll. 7-8). Obviously, the intent here is to suggest that the Union shall receive a divine punishment like that Cain endured for killing Abel, and that the Confederacy will share in the fate of the crucified Christ. But Ticknor expressed the idea far more explicitly in an 1869 poem entitled “South in Memorial.” This poem, when first published in 1865 under the title “Cordelia! Cordelia!,” was a straightforward elegy, with no hope of redemption for the Confederacy. This was the version contained within the 1879 volume. But the 1911 volume includes instead a rewritten version from 1869, now with the “South in Memorial” title and “Cordelia! Cordelia!” as the subtitle, that comes to a very different, and far more millennialist, conclusion.

Both versions of the poem imagine a funeral for the Confederacy. However, whereas the 1865 form of the poem is content to simply depict the Confederacy receiving a Christian entombment, the 1869 version ends by drawing a parallel with another entombment, one that is at the heart of Christianity. In this version, Ticknor affixes three new stanzas to the end of the poem. It is not the most felicitous emendation, as the new stanzas clash with the previous in tone, rhythm, and subject matter. They cannot help but jolt the reader by how sudden they seem and how much they break from the previous lines. But, by a happy accident, this serves Ticknor’s purpose quite well, given that these stanzas forecast another kind of disruption, one foreshadowed two-thousand years ago in the Levant:

’Tis a proud monument they rear,

By this proud pathos of Judea—

This Roman scoff that fronts the skies—

Watching lest Righteousness arise!

Watch, Eagle!—for a tale is told

Of slumber on thine eyes of old—

Of triumph, blind; of tears that kept

The better vigil that they wept.

Watch, Roman! lest the dawning hour

Write dust and ashes on thy power—

And retribution, swift and dread,

Rise with Righteousness from the Dead! (“South in Memorial” ll. 29-40)

Here, in his own bombastic fashion, Ticknor attempts to draw a direct connection between the Confederacy’s fall and the aftermath of Christ’s crucifixion. When he speaks of “the proud pathos of Judea,” he is referring to the mourning and downcast South and the “Roman scoff that fronts the skies” alludes to the Union victory. Thus, Ticknor casts the South as occupied Judea and the Union as the Roman occupiers. But the fact that the victors are watching “lest Righteousness arise” indicates that this is not merely the general situation of the first century he is referring to but to a specific incident in the Bible: the Roman watch over the entombed body of Christ following His crucifixion.

Never one to be subtle in his allusions, Ticknor begins the next stanza with the phrase, “Watch, Eagle.” This references the fact that the eagle is the national bird of the United States—hence it is the Union he is addressing. But it also alludes to the Roman usage of the eagle as a national and military emblem, thereby drawing what Ticknor thinks is a clever connection between the two powers and justifying—in his own mind, at least—his equating of them. Ticknor uses the phrase “triumph, blind,” a commonplace reference in his poetry for the Union victory, to indicate that he is still talking about the outcome of the Civil War, despite his biblical posturing and the line “a tale is told” makes clear that Ticknor is applying the old story to modern times. And yet, while Ticknor sets up to instruct the triumphant Union based on the example of the past, he cannot stop himself from treating current figures and events as though they were literally the same as past ones. He speaks of “slumber on thine eyes of old” as if he believes that the Romans and the Union are the same entity persisting through time—an idea which, if taken literally, would undermine his point about the transience of each nation’s power. Altogether, then, he takes great pains to convey the idea that the Union is equivalent to the Romans who crucified Christ. Such a blunt and unambiguous identification leaves only one possible conclusion about who the defeated Confederacy must be.

This, of course, is Christ himself. Despite Ticknor’s earlier clumsy mention of Judea that had seemed to set up an identification of the South with the Jewish people, it is specifically Christ that Ticknor wants his readers to see as representing the Confederacy in this allegory. He makes this clear in his final stanza. For as the Romans (the Union) celebrate their triumph, “retribution, swift and dread” will “rise, with Righteousness, from the Dead.” This poem has gone to great lengths to portray the Confederacy as a body given a funeral and placed in a tomb. Now, we are told, the dead body in the tomb will come to life again, just as Christ did in His tomb nearly two-thousand years before. Ticknor here likens that regime not only to Christ crucified but to Christ resurrected. He clearly believes that the Confederacy itself will rise from the dead, just as Christ did. Furthermore, since it was God who raised up Christ, Ticknor’s identification of the two implies that it will be God who intervenes to restore the Confederacy to life. This means that, in Ticknor’s mind, the Confederacy holds a central place in God’s plan not unlike that of Christ himself.

This would all be quite a lot to take in on its own. Ticknor’s identification of the Confederacy—a social order centered on the oppression of Black people—with the oppressed and crucified person of Christ is suspect enough. It is also blasphemous, given that Ticknor once again seems to forget that there is a distinction between the Confederacy and the historical individual that he is paralleling it with, an individual that is, for him, God. But there is an even darker note to Ticknor’s prophecy. He warns the Union that “the dawning hour” will write “dust and ashes on thy power” and furthermore promises that “retribution, swift and dread” will accompany the Confederacy’s return to life. Ticknor cannot be drawing this from the Gospels. Jesus’s resurrection did not signal the end of the Roman Empire or any great moment of divine vengeance on it. The Roman Empire survived long enough to adopt the man it had once crucified as its only God. Ticknor’s anticipation of what awaits the Union is far more vicious and final than that. It is, in a word, apocalyptic.

When the Confederacy is raised up, the Union will be brought low. When God brings life to the Confederacy, he will bring retribution and destruction to the Union. There will be a final settling of accounts, in which the Union’s defeat of the Confederacy is reversed through divine intervention, such that the Confederacy is brought back to life and the Union annihilated. Ticknor expects that God’s intervention will bring about a final kind of justice in which the wrongs of history are righted and those he considers righteous at last prevail. This, it goes without saying, is a fundamentally millenarian idea, albeit a dark and grim one. It conveys in broad strokes what Christians expect to happen at the end of time. But Ticknor has now with the Confederacy placed front and center of those expectations.

By this time, Ticknor had come to see the Confederacy’s fate in strictly millennialist terms. It had fallen in history but would be revived as God’s coming kingdom on earth. One poem in particular, entitled “Atlantis,” demonstrates not only this belief, but the strange forms it could take. In this poem, rightly included among the war poems in the 1879 edition but bizarrely placed in the 1911 edition’s humor section, Ticknor identifies the Confederacy with that fabled sunken continent and promises that someday “Atlantis” (the South) will rise again from the sea. It is a peculiar poem built upon a bad analogy; the Atlantis of Plato and later tradition is not expected to rise from the sea. The unsuitability of the metaphor is especially apparent when Ticknor laments the fact that the Union, in its “triumph blind” (“Atlantis” l. 24)—that phrase again—“hath furrowed the sod / To hillocks that cry to God,” (ll.25-26) and will be able to “toil in the sunless stain / Where our lost Atlantis sleeps” (ll. 29-30), painting an outlandish picture of the Union tilling soil that has already firmly lodged itself in the depths of the ocean.

Ticknor’s millennialism in this poem is similarly confused. He says that “Atlantis” (the Confederacy) will “tarry a thousand years / Till her Angel of Light appears” (ll. 31-32). These lines, the last of the poem, bizarrely imply that it is the Union that will become the long-promised millennial kingdom, as the South will be under its yoke for a thousand years until the very end of time. Given Ticknor’s hatred of the Union, this surely cannot be what he wanted to suggest, and it must be that his understanding of the Christian end-times is rather garbled here. Still, the fact that an “Angel of Light” will come at the end to raise up the Confederate Atlantis demonstrates that Ticknor believed that the Confederacy’s restoration would happen at the end of days and that it would be God, working through an angel, who would bring it about. “Atlantis” serves to confirm the millenarian implications of “South in Memorial,” demonstrating that Ticknor does indeed see the Confederacy’s rising again as a key part of God’s final triumph and the establishment of His reign upon earth. For him, the Confederacy’s return will be as much a part of that apocalyptic program as any of the events in Revelation.

It was a brazen move, one that is both highly unorthodox and deeply unhinged. American nationalistic millennialism was always rather myopic, given its singular focus on the United States as the instrument of God’s final unveiling. And yet, Ticknor’s instance that it would not be the United States as a whole, but a sectional regime that had failed after only four years, was far stranger and even more extreme. But it got even stranger when Ticknor, still trapped in a romantic view of the Middle Ages and newly enamored by Tennyson, decided to bring his old hero, King Arthur, into the apocalyptic mix. The result was “Arthur the Great King,” the poem that closes out the “War Poems” section of the 1911 volume.

Works Cited

I. M. P. O. “Dr. Francis O. Ticknor.” Woman’s Work, vol. 1, no. 8 (1 May 1899): pp. 174-176.

Kent, Charles W., editor. Southern Poems. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1913. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t4fn13s1w

Link, Samuel Albert. “Dr. Frank O. Ticknor.: ‘The Lyric Poet of the South.’ The Independent, vol. 41, no. 2114 (6 June 1889): pp. 5-6. Pioneers of Southern Literature. Nashville: Barbee and Smith, 1896. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hx5a2g

Matsui, John H. Millenarian Dreams and Racial Nightmares: The American Civil War as an Apocalyptic Conflict. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2021.

Neale, Walter, editor. Masterpieces of the Southern Poets. New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1912. Web. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t6834cf6r

Philips, Jason. Looming Civil War: How Nineteenth-Century Americans Imagined the Future. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Smith, Charles Alphonso. “Francis Orray Ticknor.” Library of Southern Literature, edited by Edwin Anderson Alderman, Joel Chandler Harris, and Charles M. Kent, vol. 12. 1907. Atlanta: The Martin and Hoyt Company, 1910, pp. 5353-5358. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.31175034925381

The two editions of Ticknor’s poetry cited above are:

The Poems of Francis Orray Ticknor, edited by Michelle Cutliff Ticknor. New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1911. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015063973849

The Poems of Frank O. Ticknor, M.D., edited by Kate Mason Rowland. Philadelphia: J. Lippincott and Co., 1879. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b274732