Everything you believe about the world can be traced back to an apocalyptic prophet who lived in the twelfth century.

Everything.

I’m well-aware that this is a bold statement to make. I do not, after all, know who you are or what you believe. But I do know that your beliefs about the world, as well as my own, and those of everyone living today have been shaped by our shared experience of the thing we call modernity. Whether you hold to “contemporary values” or reject them, whether you stand on the left or right, whether you consider yourself a free thinker or an intuitive soul, the fact of living in the modern world, of being modern, has played a role in what you believe and why you believe it. You are a child of modernity, whether you accept the fact or rebel against it, and a product of the world modernity has made.

By modernity, I do not merely mean the basic sense of living in modern times. After all, every period has been modern to those living through it. What I am talking about is modernity as an abstract concept, the distinctive quality that we believe characterizes our own times as opposed to previous ones. Modernity, in this sense, is viewed as a break from all that came before. Most people living in the world today have a sense that our days are fundamentally different from those of the Middle Ages or of Antiquity and that we can never go back to those very different times. There was, we tend to believe, a moment in time when things ceased to be ancient and became modern, when a discontinuity opened up between what the world was then and what it is now. In short, the dawning of a new age. It is this sense of discontinuity, of a complete break from what came before, bringing with it the birth of something entirely new in human history, that defines our collective understanding of modern times.

What exactly constitutes the break with the past is a question whose answer differs from person to person. But a few key factors are usually cited: secularism, science, and technology, and the whole constellation of ideas that are bound up with them. The general sense is that modernity is different from the past because we moderns have banished extraordinary beliefs and all that has been termed “superstition,” that we have built societies upon rationalism and logic rather than blind faith, and that our scientific and technological advancements have made us as a species immune from backsliding into the darkness of earlier ages. The philosopher Charles Taylor calls this the “secularization thesis” (Taylor 22), and its proponents argue that modernity began at the moment when humanity—Western, white, European humanity—placed its faith in reason and let go of all the extraordinary, overzealous, and sensationalistic supernatural beliefs that had previously guided civilization. It goes without saying that, for such thinkers, apocalyptic notions and millennialist thinking sit at the top of that pyramid of outdated belief.

It is a pity for them, then, that the concept of modernity itself is the creation of an apocalyptic prophet who lived in the twelfth century.

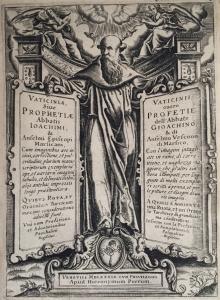

Joachim of Fiore is not someone who you usually find on the syllabus in a standard course on the history of ideas. His thought, rooted in Biblical prophecy and millennialist expectation, does not fit neatly into the easy narrative of a modern world made by intellectual advancement and scientific rationalism. And yet, no serious scholar would deny the decisive role he played in turning Europe—and hence, the world—from the unchallenged domain of priests and kings into a place governed by a very different set of ideas. Norman Cohn, in The Pursuit of the Millennium, calls Joachim’s ideological system “the most influential one known to Europe until the appearance of Marxism” (Cohn 99), an opinion quoted with approval by both Richard Kyle in The Last Days Are Here Again and Geoffrey Ashe in Merlin: The Prophet and His History.

They are not wrong in their assessment. Joachim’s fingerprints can be found all over the last eight-hundred years of Western history, if one knows where to look. Dante, in the Divine Comedy, placed Joachim in the Heaven of the Theologians and averred that he “was endowed with a prophetic spirit” (Paradiso XII:141), Christopher Columbus cited Joachim’s prophecies as justification for embarking on the fateful voyage across the Atlantic and the missionaries who subsequently set out to bring Christianity to the New World were devoted students of his thought. And the life and legacy of the greatest saint of the Middle Ages, Francis of Assisi, simply could not have been what it was if not for Joachim’s influence.

Joachim’s influence has remained strong into far more recent times, long after the Enlightenment supposedly ended the influence of apocalyptic faith. Kyle notes that “Abbot Joachim’s theory of three ages of historical evolution impacted many future philosophies, including those of Gotthold Lessing, Friedrich Schelling, Johann Fichte, Georg Hegel, Auguste Comte, and Karl Marx.” (Kyle 48). His name and ideas haunt the pages of literature from Roger Bacon, Boccaccio, and John Gower to Henrik Ibsen, Matthew Arnold, and W. B. Yeats. No less an authority than Oswald Spengler, in his famous Decline of the West, spoke of Joachim as standing “on the very threshold of the Western Culture” (Spengler 19) and leading Europe into that new epoch. As little known as his name is today, a glance over the pages of history reveals that no one else has exerted quite the same amount of influence upon the individuals, events, and ideologies that made the modern world as the medieval mystic who dwelt amongst the foothills of Calabria.

To comprehend how Joachim of Fiore invented the modern world and, indeed, modernity itself, it is necessary to understand that he invented another, closely related concept, that of the future. Again, this is not to say he came up with the idea that there will be a future, that tomorrow will follow today just as today followed yesterday. But he is responsible for the vast complex of interconnected ideas that we now associate with “The Future.” Our visions of the future, it is true, may have a sci-fi coloring that would be alien to Joachim. And yet, we moderns—at least until the turmoil of the last few decades—have traditionally viewed the future in a particular, rather utopian way. It is seen as a period of time distinct from our own and better than our own. And yet, it is not completely disconnected from our days but is the direct outgrowth of them. Furthermore, the future itself shall be continuously evolving and developing, with moment of progress after moment of progress, as life in this world edges ever closer to perfection. This sunny, optimistic view of the future has exerted a tremendous hold on society for centuries and was dominant as recently as the 1990s, when Francis Fukuyama famously proclaimed the “end of history” had come with the collapse of Soviet communism. But the idea has much older roots, having sprung directly from the mind of the Calabrian abbot himself.

It is true that visions of a future that differed markedly from the present existed before Joachim. We have covered many of them here. Apocalyptic and millennialist visions had long proclaimed the imminent arrival of a future state that was fundamentally different from the present and the past. Christianity was, in its earliest days, one such vision. Jesus’s claim to be the long-prophesied messiah naturally turned his disciples’ eyes toward the future and, in the first century, they believed that his Second Coming was just around the corner. There was an excitement about the future and its potential amongst the earliest Christians; it was, after all, the preserve of the Lord’s return and millennial reign over the earth. A transformative change was on the horizon and they knew that they would not have long to wait.

But wait long they did. Years, decades, and centuries rolled by. Still the Lord did not return. A disheartened Church took comfort in Jesus’s reminder that “about that day or hour no one knows … no one but the Father” (Mark 13:32). It was obvious that Christians would have to accommodate themselves to a world in which Christ’s glorious arrival was not soon to come. That meant turning their backs on the future and the excitement that it had previously generated. The process was already underway during the composition of the New Testament and can be glimpsed in texts, such as Paul’s Second Letter to the Thessalonians or the Second Letter of Peter, that preach caution and patience in the face of the breathless anticipation that runs through others. But this rejection of the future and its radical, millennialist potential would only reach its fullest development a three centuries later, in the thought of that greatest of theologians, St. Augustine.

Augustine advocated for a position known today as amillennialism. He believed that the thousand years of Christ’s direct rule described in Revelation 20 was to be understood symbolically as representing the lifetime of the Church. Because the Church was the body of Christ, its own rule over the earth was Christ’s rule and thus there was no need for Christ to physically return or set up a thousand-year paradise on earth. In Augustine’s reading, the Millennium turns out not to be so millennial after all. It is, in fact, our present age, with all its attendant troubles and tribulations. Instead of universal peace, there is the unending struggle between flesh and spirit, between the City of Man and the City of God. Christ will still return someday but only at the very end of time, when the whole universe is dissolved to make way for the new heavens and new earth. The world as we know it, however, has reached its final stage of development. Rather than a coming era of bliss, all that a Christian could now realistically expect is that the current state of affairs would continue until the very end of time.

As Peter Müller-Goldkuhle notes in “Post Biblical Developments in Eschatological Thought,” the result was that, in Augustine’s formulation, “[t]he present lacked all eschatological dynamism; growth and development could only take place spatially, insofar as the empire extended its rule over additional peoples” (30). The amillennialist viewpoint had a conception of the future in the most basic sense, in that it accepted that time would continue to flow forward and tomorrow would follow today. But it lacked any real sense of futurity, any notion of further development or change. All times to come would be, at a fundamental level, just like the times that Augustine knew. In that formulation, time did not mean much beyond the mere fact of its passing. The important events that would make a difference, the Second Coming, the Last Judgment, and so on, were not even in time but in the eternity beyond it.

Augustine’s message was perfectly suited to an ecclesiastical institution that had, after centuries of persecution, found itself in a position of incredible and far-reaching power, and so the Church promulgated Augustine’s amillennialism as official doctrine. While millenarian thought never totally went out of fashion, the Church’s choice was a blow to its popularity, and a non-apocalyptic worldview remained dominant in the West throughout the early Middle Ages. The famous myth of anxious churchmen huddling together, fearful of the end, as the year turned from 999 to 1000 A.D. is, as it turns out, just a myth. Instead, the general consensus of the time saw the future as flat, static, and ultimately incapable of change.

And then came Joachim. When the Church granted the Calabrian permission to publish his musings on Biblical eschatology, they had no idea that this would spark a revolution in how the Western world thought about the time to come. It is often said that Joachim completely overturned Augustine’s system. That is not entirely true. Joachim accepted a handful of Augustine’s basic tenets. For him, as for Augustine, Christ would not rule directly on earth. Instead, He would be represented by the faithful who would carry out His work during the millennial era. But Joachim broke with Augustine in one very fundamental way; he insisted that time was not static. Instead, it was dynamic. Time was not simply going to stay the same from the moment of Christ’s incarnation until the final end of everything. Rather, it was in a constant state of movement and development, with every moment contributing to the process that brought the fulfillment of God’s plan ever closer.

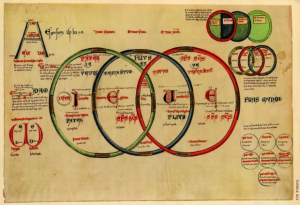

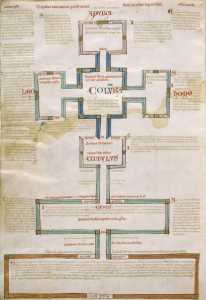

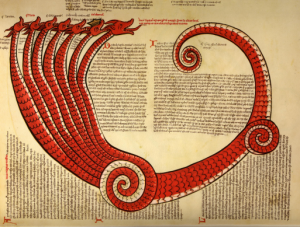

Joachim expressed this new understanding of time through his most famous concept: the Three Ages of history. In this scheme, Joachim divided the history of the world into three separate, albeit overlapping, periods of time. While it is easiest to speak of them as “ages,” Joachim himself did not choose any of the usual Latin equivalents of that word, instead opting to call them status. By using this ambiguous term, Joachim signified that each period was defined not just by duration but by the unique qualities that would distinguish life in each. He describes the Three Status and their defining characteristics in his first major work, the Liber Concordie or Book of Concordances:

For indeed there was one time of in which men lived by the flesh, which lasted until Christ, of which the initiation was made in Adam; another in which they live between the other two, between flesh and spirit, which runs up to the present time, of which the initiation was made from the prophet Elisha or from Uzziah, King of Judah; and another in which they will live by the spirit, which will last until the end of the world, of which the initiation is from the days of St. Benedict. (Lib. Con. 2.1.14)

The three ages were tied directly into Joachim’s understanding of the Holy Trinity and its workings in history. Each status corresponded with a different person of the Christian Godhead. The first age was the Age of the Father. This corresponded with the Old Testament, the Kingdom of Israel, the sacred lineage of patriarchs, judges, and kings, and the Jewish dispensation as a whole. It was the time when the materialist and worldly life of “the flesh” prevailed. The second age was the Age of the Son. The seminal event of this age was, of course, the incarnation, life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. It was the time of struggle between the flesh and the spirit, between humanity’s baser instincts and higher spiritual callings. While this age properly began with Christ, Joachim actually suggests that it first began manifesting some seven-hundred years earlier, in the time of King Uzziah. The abbot does this so that the Age of the Son may cover the whole process by which God transferred His authority from political to religious institutions, culminating in the New Testament, the Catholic Church that exerted power over kings and nations, and the Christian dispensation itself. Joachim describes the difference between the first two ages thusly:

For, just as in these who were called fathers up to Christ the likeness of the Father was venerated, so too in these who were redeemed through the blood of the Son and born from water and the Holy Spirit the image of the Son himself can be venerated, He who wished to have brothers on earth, despite being Lord of all and creator of the universe, that He himself may be as Paul said: “Firstborn among many brothers.“ (Lib. Con. 2.1.7)

In Joachim’s formulation, the Age of the Father saw earthly “fathers,” be they heads of families, tribes, or kingdoms wielding supreme power on earth in God’s name. But when the Age of the Son came, this power transferred to the select brotherhood of Christ, the priests of the new Christian church. With God’s chosen nation vanishing in the Babylonian captivity, the locus of God’s rule over the earth would shift from political organizations to religious ones. First the postexilic Jewish priesthood and then the transnational Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy would become the new conduits of God’s interaction with the world. As such, the Age of the Son would be coterminous with the birth, development, and flourishing of the type of organizations we normally include under the term “organized religion.”

This, of course, continued to be the shape of things in Joachim’s own day. But if he himself was living in Second Status, that meant the last age was still to come. There would be a further transfer of power as God began to build a new relationship with humanity beyond the confines of the priesthood. Joachim saw the first glimmers of the new age in the life of St. Benedict (c. 480–543 C.E.) and his followers would see it in that of St. Francis of Assisi. But, even if the transition was already underway, the true birth of the new epoch would only come about in the future. This future aeon would be, as Joachim says in his De Ultimis Tribulationibus [On the Final Tribulations], “that Third Status pertaining to the Holy Spirit with the quality of mystery” (De Ult. Trib. 189). The Age of the Holy Spirit, he promised, would be utterly transformative. The many corruptions and injustices in the Church and the world would finally be redressed. The Church would renounce all its accumulated wealth, power, and influence and would instead return to pure spiritual path of Christ. The unity of Christianity, wrecked by the Great Schism, would be restored, and even the Jewish and Islamic peoples would be united under the true faith. Real peace would finally exist throughout the earth and people everywhere would prosper until the end of the world and the coming of the new heavens and new earth.

This is very clearly a vision of the Millennium. In many ways, it harkens back to forms of millennialist thought that we have already encountered. Müller-Goldkuhle is right when he suggests that “Joachim did manage to recapture something of the dynamism of classical Christian eschatology” (Müller-Goldkuhle 33). Certainly, Joachim was almost single-handedly responsible for reinserting the original conception of a real and imminent Millennium into mainstream Christianity after nearly a thousand years of Augustine’s symbolic and abstract interpretation. It is also chiefly due to his influence that the Book of Revelation—in whose symbology his system was firmly rooted—reclaimed its place as the standard Christian narrative of the end-times from the Apocalypse of Methodius and its attendant texts. He made belief in the words of Revelation and the promise of an actual Millennium a viable theological position once again and, if this had been the extent of Joachim’s contribution, it would have secured his place as one of history’s most influential Christian millennialists. But Joachim went even further and did something which no millennialist before him had ever managed.

That new thing was the concept of change. As Marjorie Reeves says in her magisterial and authoritative The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages, “The historical significance of Joachim lies in the dynamic quality of certain key ideas which he proclaimed” (Reeves 135). We have noted already how static Augustine’s vision of the future was; tomorrow would be just like today, and the day after would be the same, and so on until the end of time. The earlier millennial visions may have allowed for a much different kind of future, but it was a future that was just as stagnant, in its own way, as Augustine’s. When the millennial age finally arrived, it was expected to be fixed and unchanging. In Revelation’s famous description of the Millennium, “I saw thrones and on them sat those to whom judgement was committed. I saw the souls of those who, for the sake of God’s word and their witness to Jesus, had been beheaded … They came to life again and reigned for a thousand years” (Rev. 20.4-5), the emphasis is on the static image of the elect on thrones rather than the processes and motions that rule over the earth would require. Though the millennial kingdom has an expiration date, there is no indication that life on the first day of the thousand years will be much different from life on their last day. There is a good reason the Millennium has traditional been compared to the Sabbath and called the age of rest.

Joachim’s Age of the Holy Spirit is not an age of rest. It is an epoch of activity. There is no stasis; the Third Status is all about change. Whereas Revelation placed the martyred dead placed upon thrones at the dawn of the Millennium, Joachim saw a new, far more active group of people taking the lead in the coming age. The Third Age, and the transitional period between them, would see the rise of what Joachim called “spiritual men” (viri spirituales). They would be part social worker, part missionary, but always the perfect image of Christ in the world. Joachim expected them to be monks but, rather than simply sitting behind the walls of a monastery as the monks of his own time did, these would be a new kind of monk who would go out into the world to live the Gospel, tend to the needs of the poor and downtrodden, testify to the faith, and generally be of service. These missionary-monks would go to the farthest ends of the earth to preach the Gospel and the message of universal peace. In their self-sacrifice, simplicity, and compassion, they would flawlessly encapsulate the way of life of the Third Age.

Joachim was well-aware of the need to balance the active and the contemplative life. Monasticism had since the beginning been centered on the contemplative side; Joachim was the first to suggest that monks ought to involve themselves in the active life as well. He foretold that this synthesis would be embodied in two new orders of monks and that these two holy orders would be responsible for ringing in the Third Age and the world’s transformation. It was a radical idea, one that broke completely with the stasis of earlier apocalyptic models. Joachim had not only inserted a new sense of activity and dynamism into the end-times scheme but had introduced something utterly unprecedented into millennial thought: a notion of progress. The world would not simply be made perfect in one fell swoop; humans would work over time to bring it ever closer to perfection.

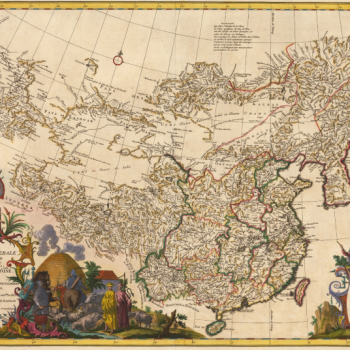

It would prove one of Joachim’s most far-reaching ideas. It was only a few years after his death that Joachim’s prophecy of two new monastic orders engaged in a radically outward-looking spiritual mission came true. In 1202, Joachim died. In that same year, Francis of Assisi was captured in battle and began to undergo the spiritual conversion that would lead him to establish the Franciscan Order in 1209. The Franciscans took both Francis’s personal example and the teachings of Joachim as the foundations on which to build the Order, and they remained the Calabrian’s most devoted disciples for generations. Another handful of years later, in 1215, the Dominican Order was founded, with a similar outlook and mission to the Franciscans. The creation of the Mendicant Orders was the most significant development in late medieval monasticism, completely reshaping both the religious life of the Church and the role of organized Christianity in the world at large. The missionaries who evangelized the New World were Franciscan, as were the first emissaries the Church sent to China and the Far East. And the role of the mendicants in later European history is too great to easily summarize. But their legacy has been vast; in them, Joachim’s vision bore remarkable fruit.

But the two new holy orders and the arrival of new spiritual men was not the limit of Joachim’s dynamism. The Calabrian abbot also proposed that the Third Age would see the unveiling of new, previously unknown spiritual truths. This was something truly unprecedented in Christianity. St. Peter, invoking the prophet Joel, had promised in the Book of Acts, “In the last days, says God, I will pour out my Spirit on all mankind; and your sons and daughters shall prophesy” (Acts 2:17)–but it had been a generally accepted since then that prophecy and revelation had ended with the deaths of the apostles, with the resulting insights being fixed and immutable. But Joachim argued that, in the Third Status, the process of revelation would begin anew. Furthermore, it would be open to all and would continue to unfold for the rest of time. Joachim believed that God would endow humans with a new mental faculty, which he called “spiritual intelligence” (spiritualis intellectus). This spiritual intelligence would develop over time, giving future generations access to spiritual insights that had been beyond the reach of those who had come before them. Joachim asserted that humanity was already beginning to manifest the new spiritual intelligence in his own day but that, as the Third Age drew near, it would become increasingly common, allowing people to study the scriptures and come upon new interpretations, new ideas, and new truths that would fundamentally reshape the practice of religion. Christianity itself would take on a dynamic, even evolutionary quality; the faith would be refined, grow, and evolve as new ways of understanding God and the world came to the forefront.

Joachim believed that even the basic structure of the Church would undergo a transformation in the Third Age. He was fond of saying that the Church of Peter would become the Church of John: “although it is necessary for the one order which itself belongs to Peter to be first brought to an end … however, the order which belongs to John will endure” (Lib. Con. 2.1.33). He argued that the bureaucratic structure of the Church, the hierarchy with its ornate titles, ostentatious wealth, and byzantine organization, would fade away. In its place, both the Church and the wider society around it would be structured on the monastic model that he held so dear, becoming far more egalitarian and communal than either the Church or the society of his time. In other words, the church of rank and power would become the church of service and love. Both religious life and human society in general would be reoriented toward universal brotherhood, mutual service, and the welfare of the community as a whole.

Joachim’s vision was remarkable for its sense of justice and thorough rejection of the way things were structured in his own time. As Marjorie Reeves says of Joachim in The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages, “Thus a most interesting aspect of the Abbot’s thought is his concern for the general body of Christian people. Here is no esoteric mystic who locks up the spiritual future within a select group while the masses perish. Sometimes he even visualizes the conversion of all peoples, including the Jews, to a new spiritual intelligence” (Reeves 140). Joachim expected the masses to share in the spiritual gifts of the Third Age. The spiritual intelligence, the refashioning of doctrine, and the communal life of the new Church would be open to all who sought to take part. For the first time, the apocalyptic moment and the millennial utopia to follow would not be the sole preserve of a chosen elect; everyone could, at least potentially, claim their share of the world’s transformation and the bliss to follow.

This was a seismic shift. Joachim’s ideas completely changed how people viewed the times to come and their place in them. As Geoffrey Ashe says in Merlin: The Prophet and His History, “Joachim and his school of thought made room in the Christian scheme of things for optimism about the earthly future” (Ashe 34). Out of Revelation’s grim imagery of destruction and persecution, Joachim found reason for hope. Even the Antichrist—or at least the worst Antichrist, for Joachim believed that each time produced its own—would not stand in the way of the Third Age’s fulfillment; he would be overcome by the steadfast faith and peaceful missionary efforts of the spiritual men. Joachim thereby liberated Christians from the fear of the end and suggested, for the first time, that the future was something to look forward to. By making the coming age a dynamic, progressive development, he suggested that life and living would continue to become better over the course of future time and that human advancement would never cease.

He also emphasized that, in addition to man’s physical and material condition, the moral and spiritual state of humanity—long seen as utterly abject and worthless in Christian thought—would also advance over time. As Delno C. West puts it, “Joachim of Fiore played a significant intellectual role in advancing the concept of the perfectability [sic] of man by contributing to the development of the idea of progress” (West 208). That idea of progress, the idea that both humanity’s material and moral states could be simultaneously improved, leading to a concrete future that would grow ever better, underlay all the developments that ushered in the modern world, from the Protestant Reformation to the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. We can recognize the echoes of Joachim’s ideas about the necessity of change, the inevitable transformation of society, and the central importance of human agency in shaping history, in all the ideas and concepts that form the bedrock of modern society. Would we have things like modern democracy, intellectual freedom, and technological innovation without these concepts and beliefs? Certainly not. And yet, these “enlightened” ideas all have their source in the mind of a mystic seeking the true meaning of the Book of Revelation.

Joachim’s theories, suitably secularized and stripped of their eschatological content if not always their apocalyptic force, form the ideological backdrop of our modern world and are deeply engrained in the collective worldview most of us share. Joachim’s influence is so vast that he not only reshaped our understanding of our place in time, but the very notion of historical time itself. As noted above, Augustine had seen time as absolute continuity, with one day being much like the next forever. The earlier millennialists, on the other hand, expected a complete break in time. The eschaton would be totally separate from historical time, brought about by God’s sudden intervention rather than anything that had come before. Joachim was the first to suggest a view of time that, while paradoxical at first glance, has since become standard: the future would be both a break from the past and a direct continuation of it. It would be a new age, but one born from the same processes and developments that had been running throughout the whole of human history.

Joachim, as we have seen, rooted his concept of the Three Ages in his beliefs about the Christian Trinity. For him, however, the Trinity was not simply the Three Persons who make up God but also the relationships and relationship dynamics that existed between them. The nature of the Trinity was a kind of spiritual movement, with the Father sending forth the Son and the Father and Son together sending forth the Holy Spirit. This meant that movement and dynamism was fundamental to the nature of God and thus had to be reflected in the world God made and its history. God’s intervention could not be limited to certain moments and awe-inspiring miracles. Rather, like the sending forth of the Holy Spirit to every believing individual, God’s working in time had to be constant, omnipresent, and immanent, manifesting through the characters, events, and developments that moved history forward.

This meant in turn that, for the first time, the millennial age would be the natural result of processes that had begun in previous eras of historical time. As Joachim says in the Liber Concordie, “what in the Second Status is proclaimed according to the letter, in the Third will be perfected according to the Spirit” (Lib. Con. 2.1.13). The future is not something imposed from without. It is a change from the present and the past, but it also comes from them. The coming Age of the Holy Spirit is an outgrowth of the Age of the Son, just as the Age of the Son is an outgrowth of the Age of the Father. For how transformative the society of the Third Age are, it bears a fundamental continuity with the society that came before. As Marjorie Reeves observes, “The third status is within history, yet not a new set of institutions: rather, a new quality of living which transforms former institutions” (Reeves 303). Thus, for example, while Joachim believed that the Church of the new age would look quite different to how it did in his day, he still expected it to have a pope—indeed, he predicted the coming of a great reforming pontiff who would help ring in the Status of the Holy Spirit, thereby introducing the figure of the Angelic Pope into the Christian end-times narrative. Joachim’s view of the future collapsed eschatology into history and made the age of perfection the outgrowth of current events, situations, and institutions. The notions of millennial disruption and Augustinian continuity had been conjoined into a holistic vision of history that saw even the greatest breaks from the past as the result of processes that had been running since time began. Time was no longer static and history was now the site of continual and ongoing development.

Joachim’s insight may seem obvious to us. We know that current or past processes can create future eras that look very different, and most of our understanding of history is built upon this observation. But this was a radically new way of viewing history in the Middle Ages. Robert Lerner says that “his theory of three ‘statuses’ was a really new conception of steady historical advance” (Lerner 118). Bernard McGinn tells us that “Joachim’s primary intention was to show that there was an intelligibility to the entire historical process … No previous apocalyptic thinker had been so persistent in this concern, so theoretical or systematic in its presentation” (McGinn 154). Marjorie Reeves, more succinctly, calls him “a poet of the meaning of history” (Reeves 132). Joachim gave a new sense of meaning and purpose to history as the guide by which we could understand how the future would unfold. As Delno West says, “by shifting the accent of God’s revelation to history, Joachim raised history to a place of supreme importance” (West 208). His prophetic method was, in fact, utterly historical; it involved comparing personalities and events from the Old Testament and ancient times to similar personalities and events of the New Testament and the Christian era, then drawing conclusions from these “concordances” about how the future would go. Joachim was the first to recognize not only that patterns recur reliably throughout history but that they can give insight into how future events are likely to play out. Our current view of historical time—summed up in the inane truism “those who forget history are doomed to repeat it”—lacks the spiritual dimension he prized but otherwise relies entirely upon his insight.

Thus, Joachim, in a very real sense, gave the world a brand new sense of time, a new way of experiencing and understanding it. As Morton W. Bloomfield says, “He was the first systematic thinker about the nature and meaning of history, and he was oriented to understanding the past so that he could understand the present and future. He was our first futurologist, even if not our first Utopianist” (Bloomfield 23). It is in Joachim for the first time that history becomes not a meaningless repetition of events or a repository of eternal truths but an ongoing process that continues to unfold in our day and deep into the future. It is Joachim who first suggested that it is this process and the activities that humans undertake within it, rather than a divine force operating completely from the outside, which holds the key to a future of hope and prosperity. He may have been the first process theologian and was certainly the first theologian of hope. He was also the first serious student of the future as a concept as well as the first thinker to seriously suggest that a better future could be made by human hands. As such, it was he, a mystic and apocalyptic prophet, who laid down the understanding of history and the future that has defined our modern age.

The irony is that our modern world seems intent on separating itself from the mystic, even if it cannot escape the apocalyptic. Joachim could never had approved of this; for him, God was still central to human history, even if it was a God who worked through history’s processes rather than around and above them. But his insights made it possible for later minds to remove God from history entirely. Charles Taylor proposed in A Secular Age that the rational, secular world of modernity, for all its pride at leaving behind the religious climate of the Middle Ages, could only have been born from the unique ideas and tenets of medieval Christianity. We can now refine this to say that it could have only been born from the tenets of one particular medieval Christian, Joachim of Fiore. The modern world kept Joachim’s insights about the recurrence of patterns and historical change and even maintained his hope in a transformative future created by those patterns and changes but abandoned the spiritual meanings he saw within them. Indeed, Joachim himself is now barely known.

This is a shame because, as Marjorie Reeves observes, “A prophet foretells the future: he can also create it” (Reeves 135). Despite his loyalty to the Church, there was something very radical and revolutionary in his teachings. The Church did not fully recognize this when it first condemned Joachim’s views in 1215. Rather, that happened because his dynamic view of the Trinity ran afoul of the stagnant, rationalist trinitarianism of Peter Lombard, which emphasized God’s unchangeable essence and cast the Trinity as merely an approximation of His true nature—Joachim declared that the Lombard both denied the Trinity and added a fourth person to it. But by the time of the second condemnation of his views—only Joachim’s ideas were prescribed, not the man himself—in 1263, the Church had finally gotten a taste of how dangerous his ideas were to their status and position in the medieval world.

The 1263 condemnation came about because a Franciscan by the name of Gerard of Borgo San Donnino had declared that the Bible was out of date and no longer valid. He said that a new holy book was needed for the Age of the Holy Spirit, and he was happy to nominate Joachim’s own writings for the position. Gerard perhaps took Joachim’s frequent injunctions to follow the spirit rather than the letter of scripture more seriously than most, but he was not alone in realizing the radical potential of the abbot’s words. As Reeves notes, “Joachim’s philosophy of history, it was now realized, constituted an incitement to subversive thought and action that was dangerously infectious” (Reeves 62). Joachim’s teachings inspired the transgressive ideology of the Guglielmites, who believed that the Holy Spirit had incarnated in the body of a woman and appointed a female pope, amongst other heterodox sects. Cola di Rienzo and Savonarola drew on the abbot’s ideas to fuel their Italy-shaking revolutions. Tommaso Campanella, a fellow Calabrian who frequented some of Joachim’s old haunts, used his thought as the basis for his great utopian work, The City of the Sun. Even amongst the orthodox, the Church’s disapproval did little to slow down the spread of Joachim’s ideas. Norman Cohn notes that “in the whole Middle Ages there was scarcely another intellectual who did so much to shake … the structure of orthodox medieval theology” (Cohn 100). For both loyal churchmen and reputed heretics, Joachim’s thought created a space in which one could legitimately oppose the actions of the Catholic Church and its leaders without having to renounce Christianity itself. This room for opposition had never existed before in the West, and certainly not in Italy, the heart of Catholic Europe. But now that it was open, that space could never be closed, despite the Church’s best efforts to do so. This rising tide of dissent would, after several centuries, find its fullest expression in the Protestant Reformation.

Joachim’s ideas provided inspiration to early reformers such as Wycliffe and Hus and proved particularly attractive to those in the movement, like the Anabaptists, who sought a theology completely distinct from Catholicism. His teachings have had a long afterlife in the many branches of Protestantism and remnants of them can be found in some of that faith’s most cherished beliefs, such as the emphasis on the individual interpretation of sacred texts and the distrust of Catholicism’s rigid hierarchy. But his influence was perhaps even greater on the newly developed secular world. Not only did he give birth to the myth of progress but all radical reformist movements, from the early utopians to Marxism, owe a debt to him. As Bloomfield says, “The political implications of Joachim have always attracted modern political theorists and the left” (Bloomfield 28). His ideas have always appealed to those who want to shake the status quo and have traditionally reappeared in times of great social upheaval, such as during the Russian Revolution of 1917 and in the counterculture of the 1960s.To both political revolutionaries and spiritual seekers, Joachim has long offered a blueprint for extreme change and societal renewal.

Ironically, the major spiritual tradition that best preserves Joachim’s thought today is not even Christian. For all its Eastern pretensions, the New Age movement is deeply rooted in Joachim’s ideas. In his hopes for the new spiritual men and his assurance of a developing spiritual intelligence, we can see the beginning of the New Age interest in spiritual evolution and humanity’s psychic gifts. The common New Age schema of dividing history into three ages—Aries, Pisces, and Aquarius—is a direct borrowing from Joachim. It reproduces the key features of Joachim’s system, including the overlap of ages and the idea that an age can begin exerting its influence centuries before its actual arrival. And the Age of Aquarius itself, the transformative age of a new spiritual consciousness, is just the Age of the Holy Spirit under a different name. Quite literally so: Marjorie Reeves has documented how St. Vincent Ferrer came up with the idea by adding astrological symbolism to Joachim’s theology of history. He declared Joachim’s Third Age to be the Age of Aquarius “because the sun of justice will then be in Aquarius: for thence shall all generations of the infidels be baptized” (qtd. in Reeves 171). Strange as it may seem, it was in one Catholic monk’s emendations to the work of another that the whole New Age movement was, in a sense, born.

All facets of modernity, even the most seemingly contradictory, bear the imprint of the Calabrian’s vision. That both secularist revolutionaries and New Age mystics owe a debt to him says something about how much his ideas have seeped into our collective consciousness. Some of this same apparent contrariness can be seen in Joachim himself. On one hand, he was a thoroughly medieval man who created his system out of numerology, symbolism, and a close reading of the Old and New Testaments. He was loyal to the idea of the Church, if not always its reality, and believed monasticism provided the best way forward for humanity. But on the other, many of his views reached far beyond those of his contemporaries and seem progressive even to us today. He, practically alone among medieval Catholics, had a deep respect for Judaism and Jewish thought. And by the end of his life, he had come to totally reject religious violence and holy war— his De Ultimis Tribulationibus even insists that God will not use actual violence at the Battle of Armageddon, but when the forces of evil are “pierced by the sword of Christ which is his Word,” this means that “they will cease to live carnally as ‘they may no longer live themselves, now Christ lives in them’” (De Ult. Trib. 188). That he was able to inhabit his world so successfully and yet see so far beyond it is a testament to his genius. In his own person, Joachim himself managed to embody the process of historical change and transformation that was so crucial to his theory of time.

For what it’s worth, he was not wrong, in the main. His theory of the Three Ages of historical time does have some evidence in its favor. As noted above, Joachim placed the first stirrings of the Age of the Son, the age of religious institutions and mature religious thought, in the time of King Uzziah. Uzziah’s reign began sometime around 800 B.C.E. Scholars today recognize that 800 B.C.E. was also the beginning of what they call the “Axial Age.” This period saw a massive leap forward in religious thought and organization around the globe. Philosophy and theology came into their own as intellectual disciplines. Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and Hinduism were all codified, became truly institutional religions, while Buddhism, Jainism, Confucianism, Taoism, Mohism, Legalism, and the various schools of Greek philosophy all came into existence. It was, indeed, the birth and flourishing of organized religion as we know it today, just as Joachim’s Age of the Son was. In this, despite working with a much more restricted dataset than modern researchers, his conclusions were right.

In turn, Joachim placed the next great leap in human development and spiritual consciousness in the Age of the Holy Spirit, which he believed would come soon after his own day. We see that, in this, he was also correct. A new, utterly transformative age did dawn. We call it modernity. It did not turn out entirely as Joachim thought it would, perhaps, but the improvements in living conditions, the collapse of old hierarchies, and the more diffuse forms of spirituality he gestured toward did indeed come about. We live in a world that certainly looks more like his Third Age than his own time would have. Modernity is still not the Millennium; that part of Joachim’s prophecy remains unfulfilled. But in some senses, our world seems closer to the millennial paradise that it ever has before.

Of course, in other senses, it seems further away than it ever has. The work begun by the Calabrian is not completed. Joachim foretold that perfection would not simply come to be but must be approached by continuous effort. That message is as much for us as for his own time. Joachim was the man who foresaw modernity. He is also, as we have seen, the man who did more than anyone else to create it. But he was also the man to saw beyond it. While we have taken our current spiritual malaise as the price of human advancement, Joachim offered a vision of progress and development that fully nurtured humanity’s spiritual as well as their physical needs, a way to be spiritual that did not require an individual to resist change and hide from the future. His vision was of a holistic society built upon universal justice and the common good; we have only just begun to approach it with small and halting steps. Joachim called mankind to its social and spiritual maturity; we have only half-heeded the call. Now, as our own age seems to be staring down its apocalyptic end, as Joachim said even his Third Age someday would, we would do well to remember Joachim always held out hope for those who were willing to strive for a better world. Our modern age, it seems, still has much to learn from an apocalyptic prophet who lived and wrote over eight hundred years ago.

Works Cited

Acts of the Apostles. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 1394-1430.

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy, translated by C. H. Sisson. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Ashe, Geoffrey. Merlin: The Prophet and His History. Stroud: The History Press, 2008.

Bloomfield, Morton W. “Recent Scholarship on Joachim of Fiore and His Influence.” Prophecy and Millenarianism: Essays in Honour of Marjorie Reeves. Edited by Marjorie Reeves and Ann Williams. Essex: Longman, 1980. pp. 21-52.

Cohn, Norman. The Pursuit of the Millennium. London: Secker and Warburg, 1957.

Joachim of Fiore. Liber de Concordia Noui ac Veteris Testamenti. Edited by E. Randolph Daniel. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series 73, no. 8 (1983). De Ultimis Tribulationibus. Edited by E. Randolph Daniel. Prophecy and Millenarianism: Essays in Honour of Marjorie Reeves. Edited by Marjorie Reeves and Ann Williams. Essex: Longman, 1980. pp. 175-189. All translations mine.

The Gospel according to Mark. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 1304-1326.

Acts of the Apostles. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 1394-1430.

Kyle, Richard. The Last Days Are Here Again. Ada: Baker Publishing Group, 1998.

Lerner, Robert E. “Refreshment of the Saints: The Time After Antichrist as a Station for Earthly Progress in Medieval Thought.” Traditio, vol. 32 (1976): pp. 97-144.

McGinn, Bernard. “Symbolism in the Thought of Joachim of Fiore.” Prophecy and Millenarianism: Essays in Honour of Marjorie Reeves. Edited by Marjorie Reeves and Ann Williams. Essex: Longman, 1980. pp. 143-164.

Müller-Goldkuhle, Peter. “Post-Biblical Developments in Eschatological Thought.” Concilium, vol. 41, “The Problem of Eschatology” (1969): pp. 42-56.

Reeves, Marjorie: The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages: A Study in Joachimism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

Spengler, Oswald. The Decline of the West. Translated by Charles Francis Atkinson. New York Alfred A, Knopf, 1926.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

West Jr., Delno C. “The Education of Fra Salimbene of Parma: The Joachite Influence.” Prophecy and Millenarianism: Essays in Honour of Marjorie Reeves. Edited by Marjorie Reeves and Ann Williams. Essex: Longman, 1980. pp. 191-215.