As some of you know I play Peter Pan part time, serving our church youth group, and frankly I have a ball doing it. We take a mission trip each summer and it’s often the highlight of my year. We go to different parts of the country, often to Indian Country, but this year to West Virginia. I wanted to have our group (eight adults and 28 youth), experience Coal Country and introduce them to the Scotch Irish and Presbyterian traditions of the South.

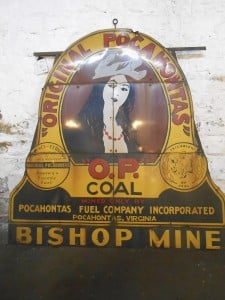

We stayed at Bluefield College, Virginia. We traveled each day into Pocahontas, West Virginia to rebuild and paint homes, repair roofs and construct ramps for disabled folks. We joined up with Group Workcamps, and so 400 adults and youth descended on a town of 300. Pocahontas is a town the coal industry left behind when the mine closed in 1955. The town was founded in 1880. Europeans, African Americans and Indians came to the town to work the mines. The history of it all is stunning: an early coal mine explosion—killing more than a 120 miners—both blacks and whites together. Their race couldn’t be determined post mortem, which on its own made history–it was the first burial of blacks and whites together in the United States. We also visited the African American Methodist Church, in which the first miner’s union was organized. We admired the magnificent churches of every stripe, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, as well as a synagogue. And to top it off, we viewed the opera house that had seen better days. Myth number one was broken: these towns were incredibly diverse, it wasn’t just the Scotch Irish, but people from all over Europe and beyond.

We stayed at Bluefield College, Virginia. We traveled each day into Pocahontas, West Virginia to rebuild and paint homes, repair roofs and construct ramps for disabled folks. We joined up with Group Workcamps, and so 400 adults and youth descended on a town of 300. Pocahontas is a town the coal industry left behind when the mine closed in 1955. The town was founded in 1880. Europeans, African Americans and Indians came to the town to work the mines. The history of it all is stunning: an early coal mine explosion—killing more than a 120 miners—both blacks and whites together. Their race couldn’t be determined post mortem, which on its own made history–it was the first burial of blacks and whites together in the United States. We also visited the African American Methodist Church, in which the first miner’s union was organized. We admired the magnificent churches of every stripe, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, as well as a synagogue. And to top it off, we viewed the opera house that had seen better days. Myth number one was broken: these towns were incredibly diverse, it wasn’t just the Scotch Irish, but people from all over Europe and beyond.

At the end of our week we drove back to Nashville and went to a water park to cool off—a much-needed break! But in buying tickets I felt that we were being over-charged, and like a good Yankee I negotiated hard. I failed miserably and threatened not to buy the tickets. A man, standing nearby, turned to me and said, in a southern drawl, “Couldn’t help but overhear your dilemma. The Lord has put on my heart that I should make up the difference between what you thought you were going to pay and what you have to pay. I was a youth pastor once too.” And he then explained how his house had experienced water damage and in a payoff he had more than benefited and wanted to “pass on the blessing.” We demurred. But then he said, “Don’t steal my blessing.” And I knew this was serious. I backed down my fellow leader and lawyer friend, and this Southern Baptist pulled out $200 and put it in my hand. I said, “Hey, will you come pray with our youth group?” He said, “Sure.” And we walked over and I told our group what had happened and their jaws dropped. I asked our new friend to pray, and before you knew it he had prayed us into a revival, long, hard and loud. Needless to say, afterwards, our youth were dazzled and dumbfounded.

On the plane ride home I sat next to a stranger. Having long ago taken the oath not to talk to strangers on planes, I broke my promise and struck up a conversation. I argued, listened and loved talking to this man for the next five hours. He was a Nashville native, a Presbyterian of Scotch Irish heritage, a hunting and fishing guide and a delightful interlocutor. We talked fish, bears, religion, the South, and how he didn’t like Lincoln, and why this lovely Baptist man had given me the money, and how the South doesn’t like government welfare because it “steals our blessing.” “For us,” he said, “This is what we do in the South, we help each other out; what that guy did for you happens all the time. We’re Christians, we have to give and by giving we are blessed.” And suddenly, the push back against Obamacare and against “government handouts” made some sense, although I still don’t agree! And my Presbyterian friend looked at me and said, “You liberal professor types will never get it!” And we agreed to disagree. But I came away “blessed” in many ways, thinking, “Maybe the South has something to teach me about helping those in need and passing on blessings.”

After we got back to the Nashville church, following our water park break, our youth said, “Let’s pass on the blessing and give the $200 to this Nashville church for them to use for their youth ministry.” And we did just that; we didn’t want anyone to steal our blessing, much less the government or ourselves.

By the way the best book on the regional cultures of American life, and particularly on the Scotch Irish, is David Hackett Fisher’s Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America.