Here’s a Ross Douthat column in the New York Times: “For Poorer and Richer.” This is another in the various columnists and bloggers commenting on the new book by Robert Putnam, Our Kids.

Here are a few key paragraphs:

. . . “Our Kids” is attuned to culture’s feedback loops, and it offers grist for social conservatives who suspect it would take a cultural counterrevolution to bring back the stable working class families of an earlier America.

That idea makes some people on the left angry. As they see it, it’s money and only money that Murray’s Fishtown and Putnam’s hometown lack and need. And it’s unchecked capitalism and Republican stinginess, not the sexual revolution, that has devastated working-class society over the last few decades. Fight poverty, redistribute wealth, and you’ll revive family and community — it’s as simple as that.

Their argument gets some things right. The American economy isn’t performing as well as it once did for less-skilled workers. Certain regions — like Putnam’s Ohio — have suffered painfully from deindustrialization. The shift to a service economy has favored women but has made low-skilled men less marriageable. The decline of unions has weakened professional stability and bargaining power for some workers.

And yet, for all these disturbances and shifts, lower-income Americans have more money, experience less poverty, and receive far more safety-net support than their grandparents ever did. Over all, material conditions have improved, not worsened, across the period when their communities have come apart.

Now, I’ve read leftist/progressive authors often enough to agree that Douthat characterizes their prescription correctly. In their telling, working class men have become unmarriageable because they can’t find jobs, simple as that. Ironically, these authors, recognizing this problem, have only minimal interest in actually helping young men — they’re pretty incidental to the project of helping single and teen mothers or increasing welfare benefits. I suppose they’ve just written off the men. (And it’s not about redistribution or such proposals as a “minimum income” if that doesn’t actually result in these men holding jobs of some kind or another.)

But let’s break apart the issue: there are two components of this “unmarriageability”: first, the bigger question of whether men contribute to the household, and, second, whether their presence actually makes the financial situation worse. And, in fact, for women without a job, getting married to a man who is also unemployed takes their welfare benefits away (doesn’t it?), without bring any income into the family. Even if he moves in without the marriage license that would eliminate her eligibility, he won’t be paying his own way. But men who work at low-paying jobs are likewise considered to be “unmarriageable”; the requirement seems to be that he be able to measureably improve her financial situation over and above what she can get from welfare or from her own job (supplemented or not by additional welfare money, like food stamps).

Fundamentally, this seems to be saying that the only use of a man is as a financial contributor to the household — both in the opinion of progressives and of poor women themselves.

And this just feels wrong. Is there not, among poor women, the same desire for companionship as motivates middle-class women to marry, even when they don’t need their husbands’ financial contribution? Consider the futuristic scenario in which anyone who chooses not to work, doesn’t have to, because automation will have changed the very concept of work: do we imagine that in that scenario, no one will bother marrying?

No, of course not. Because the unmarriageability of poor men extends beyond the mere fact that they are unemployed. I read a book quite a while ago called “Promises I Can Keep” about poor single mothers (this was right when I started blogging and it was one of my few kindle book purchases, which meant that I didnt’ get very far in summarizing the book after I read it, as I’m simply not accustomed to kindle-reading, but here’s my summary, parts one and two, for what it’s worth), and the stories these women told — well, you know how women often joke that they have four boys, rather than three, because their husband is just another kid, because he likes his “toys” (e.g., the Lego Tower Bridge from last Christmas)? Well, these women considered the men in their lives, whether dating relationships (which as often as not included children), or live-ins, to be as much trouble as their actual children. It’s not just a matter of whether they contributed, or had the potential to contribute, to the household financially, but that didn’t contribute in any way at all (not with the household chores, not with the childcare), and they were more trouble than they were worth, if they spent their time drinking, gambling, partying, in gangs, or just plain cheating on them.

A while back I read another book, specificially on black families and the “Great Migration” from southern sharecropping to northern cities, which essentially portrayed poor black families as, for the most part, troubled, even in the pre-Great Society, pre-welfare for single mothers days, not the romanticized Logan family of Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. Essentially, poor black men were just as unmarriageable then, but poor black women married them anyway.

So what happened? Did the rise of the welfare state and changing cultural norms free women from men they didn’t want to have anything to do with, anyway?

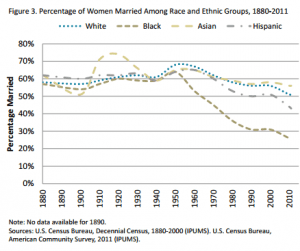

One last thought: here’s a graph on changing marriage rates from the National Center for Family and Marriage Research.

This graph shows that marriage rates have been dropping since the late 1940s and levelled off in the mid-80s. (I tried to find the data itself, to better identify the years and produce something more scaleable, but failed to find year-over-year data source.) There is no simple drop-off at the start of the War on Poverty; just the same rate of decrease as before. What happened, then? I don’t know.

(And, yes, I went from talking about poor men, in general, to black men — but the decline in marriage is similar for both groups, and I was able to find data on the latter more easily.)