Diapers are in the news lately, due to a new White House initiative in which a Silicon Valley e-commerce startup, Jet, will be working with diaper manufacturer First Quality, to

lower the price of diapers for the low-income families who struggle to afford them. By modifying diaper packaging and streamlining shipping processes along the lines of on-demand models like Amazon Prime, the project will allow nonprofits to quickly buy diapers in bulk online for distribution to families who need the assistance,

as reported by Yahoo. The effort is intended to cut the cost of the diapers themselves, by eliminating aspects of the packaging cost that are driven by the need to market and sell at stores (these are “Cuties” diapers, which seem to be some type of private label manufacturer), and by shipping them in an “on-demand” fashion so that the nonprofits don’t need a large warehouse. This, Yahoo reports, will cut the unit cost from 50 cents to 13 cents.

Now, this is a bit odd — if I look online at Walmart.com, they already sell private-label diapers at 19.77 for a “value” box, of between 160 size 2 diapers (that’s 12 cents each), 124 size 4 diapers (16 cents), or 92 size 6 diapers (21 cents – but size 5 and 6 are really only for the late potty-trainers), which means that the claims of extreme discounts are exaggerated. Perhaps the 50 cent diapers are to be found in high-cost areas, and at convenience stores in those high cost areas, and those diapers are purchased by parents who lack the transportation options to carry diapers from a retailer who sells in bulk, and lacks the cash to pay for a larger purchase at once, or is unbanked and cannot buy online. More likely, most poor families do attempt to purchase their diapers cheaply, but, even at Walmart prices, diapers are still a budget-buster for extremely low-income families — and cloth diapers are not a solution for children in daycare (they don’t accept them) or in places where mothers don’t have access to washing machines (it’s a no-no at a laundromat) or are short on time, especially when those mothers work and have long commutes.

And there have been a spate of reports about this over the past several months — taking a new angle, not just that it causes hardship for families, but that there are health issues: both that the children are at risk of rashes and infections if dirty diapers are kept on for too long, and that it affects the mothers’ mental health. See, for instance, this Atlantic article, and yesterday’s Slate article, which cites a study which hopes to make the case that providing free diapers through Medicaid would be cost-effective, by alleviating health issues. (Personally, I think it’s unlikely that they’d be able to make this case — and I say that as a mom of three who, by the time the third came around, went from changing diapers at the first sign of wetness to taking my time, with no ill effects, and gaining a fair bit of skepticism for instructions to change the baby constantly, especially given modern diapers’ ability to absorb wetness without irritating the skin. So I can believe that rashes are an issue, but not an epidemic, and solved via diaper ointment.)

But here’s the bigger issue: the Slate article linked to describes several legislative and other proposals, and they all center around provision of diapers to the poor, for instance, through daycare centers, via vouchers, or directly, in the same manner as food pantries (except government provided, rather than via charity). It links to a description of a pilot program, in San Francisco — though at the time, the program was new, and there are no more recent reports describing how it’s faring.

Is this the right approach? The bigger question is this: to what extent should government programs for the poor consist of provisions of specific items — food, diapers, housing — rather than general cash assistance? And how far should it go? There’s general agreement that daycare should be funded, for the obvious reason that it enables the poor to work, though there are disputes about whether expensive daycare centers should be covered, or just lower-cost home daycare. It’s also already a given that the poor receive free healthcare, and free contraceptives, but I think it’s hit or miss whether such items as eyeglasses and dental care are funded by the state or not. Heating is covered, and a telephone, though I’m not sure about electricity. There’s now some discussion of free menstrual products. Should poor families get clothing allowances, or shoe allowances? What about free mass transit (one of the biggest holes in everyday needs)? Vouchers for household goods, such as dishes and cookware?

(Of course, for many of the poor, the notion that housing should cost 1/3 of one’s income, is thoroughly upended by the distorted housing markets of high-cost areas, and the fact that our subsidized housing programs are the one type of assistance for the poor that is lottery-based rather than uniformly provided — literally lottery-based, as the norm is to hold a lottery for the chance to be put on a subsidized housing waiting list. And that means that families who should “have enough money” according to the definitions of poverty, spend so much on housing that they are left seeking help for their other needs.)

Or should all of this be replaced by a simple cash benefit, in the form of traditional welfare and/or an enhanced EITC (earned-income tax credit) for the working poor — with the recipients themselves left to decide how to spend it?

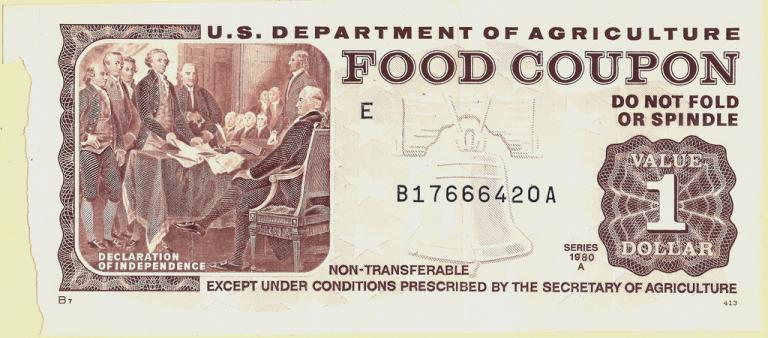

Image from http://www.publicdomainpictures.net/view-image.php?image=17551