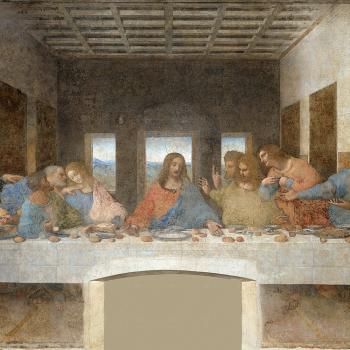

![https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACaster_Semenya_London_2012.jpg; By Tab59 from Düsseldorf, Allemagne [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/533/2016/08/800px-Caster_Semenya_London_2012.jpg)

She won the gold in the women’s 800 meter race Friday, with a time more than a second ahead of the silver medalist. That time, 1:55.28, set a record for South Africa, but was two seconds shy of the women’s world record. For comparison, the 54th and last place men’s finisher had a time of 1:54.67.

Semenya’s participation in the Olympics raised quite a bit of controversy. While no medical records have been made public, the general understanding (from the Observer) is that

As an intersex individual reportedly born without ovaries or a womb, Semenya has internal testes which produce testosterone levels more characteristic of men than women.

As the Observer summarizes,

Semenya burst onto the scene in 2009, dominating the world championships and soundly defeating the world champion at age 18. The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), the governing authority of world track, banned her for 11 months, then allowed Semenya to compete again—on the condition she either undergo surgery or chemical treatments to reduce her testosterone level.

Chromosomes now determine “fairness,” but those tests, too, fail to capture the female essence. Claiming testosterone as the characteristic male substance and key natural performance-enhancer, the IAAF issued a new rule in 2011 mandating that a female’s testosterone level be less than 10 nanomoles per liter of blood.

After undergoing treatments, Semenya competed in the 2012 Olympics, but her performance level dropped substantially with her reduced testosterone. She managed to win the silver medal, however, losing to a runner who the World Anti-doping Agency later recommended be banned for life. Then last year, Indian sprinter Dutee Chand challenged the testosterone regulation before the highest court in world sport, and won. The court suspended the IAAF’s testosterone regulations for two years, demanding the organization justify and clarify its rules.

Without her testosterone artificially suppressed, Semenya recorded the fastest time in the 800 in the last seven years.

So what’s fair?

There is no one answer here.

But before we start in on it, let me tell you a few things I learned about the Paralympics.

You see, if you had asked me about it, before I spent some time reading Wikipedia, I wouldn’t have been able to call to mind nothing much more than amputees racing on springy prostheses, and wheelchair basketball, and a vague impression of warm-and-fuzzy TV ads. But it’s actually really complex.

Take wheelchair basketball. It’s not as simple as anyone who uses a wheelchair competing, but, since all players who use wheelchairs are not alike, they are classified with a certain number of points, and the team as a whole must not exceed 14 points per team on the court.

A one point player is someone with “significant loss of trunk control,” so that they have to hold onto the wheelchair with one hand rather than using both hands for playing. A two point player has partial trunk control. A four point player has normal trunk control, and includes some amputees, and a 4.5 point player includes below-the-knee amputations. A five point player, in some cases, is for players without disabilities who are joining the disabled players by playing in wheelchairs.

For competitions such as swimming and track and field, there are a great number of categories. For track and field, there are multiple wheelchair categories, and further categories for ambulant athletes who nonetheless have some sort of cerebral palsy or a similar impairment affecting muscle tone and co-ordination. The most mild of these categories, at least as described on Wikipedia, that I can tell, is the T38 classification — which is interesting because at this level, well, it’s not entirely clear to me whether all participants have an unmistakable and obvious disability, or whether there are, in fact, disputes at the margin, whether an athlete qualifies for paralympic competition, or is just on the other side of the threshold to be a perpetual last-place finisher in non-disabled competitions.

Of interest, the record for the men’s 100 meter race, for the T38 class, is 10.79. For the T43 class, below-the-knee amputees, it’s 10.57 seconds. This compares to a time of 9.57 seconds for unimpaired men. The fastest woman ran at 10.49 seconds.

Are these classifications right or wrong? Should they exist at all?

The above Wikipedia article also has a section noting that nearly all the very top racers are West African, or of West African ancestry, and that these ethnic groups tend to have specific physiological differences, do to genetics, that provide advantages. Do they have an unfair advantage? Should there be separate classifications, and separate medals for athletes without those genetic advantages?

And now there’s Semenya.

Why, after all, are there women’s competitions? Is it because women are, socially, different, and the team, and changing room, dynamics would be different in a co-ed environment? No, of course not. We all know that if women were placed alongside men, women would disappear from sports, due to the greater height, muscle development, etc., of men. (Though we don’t like to acknowledge this — especially in the Olympics, when we measure “how good” an athlete is by how many medals they win, competing in their own “class,” or for how many years they remain at the top of their competitive class, or by how great a margin they won, rather than their absolute speed or other metrics.)

What if, instead, we had different classifications, based on height, and some kind of metric of the “natural” muscle development, the amount of testosterone, etc.? In this system, it’d be clear that women or intersex or transgender people who exceed the metrics defining the “testosterone-caused natural muscle development” and/or testosterone metrics themselves simply would fall outside the classification of “women” in the same way as, due to medical advances, a partially-paralyzed para competitor who regains measurable trunk control would be moved up a level in wheelchair basketball classification.

Would it be fair or unfair to require Semenya to compete alongside men because that’s what her underlying physiology dictates? What about a transgender individual with all the height and muscle development that goes along with male puberty, even though now taking estrogen? I suspect that many defenders would answer “unfair” because, in both cases, they socially identify as women and it would be perceived of as mean-spirited to prevent them from competing with those whom they identify as being of the same gender. Others would say that, whatever their natural athletic ability, they are clearly unable to perform at the same level as men. But that’s true for any situation in which you’re moved from one category to another — from the individual who’s just barely placed in the upper qualification tier, say, the T38 class rather than T37, or who is deemed not to qualify as disabled at all but still lacks the muscle tone and coordination to do well in athletic activity, or an individual who measures out at a 71 IQ and is thus ineligible for the intellectual disability class.

Heck, I’d be more motivated to train for that 5K if there was a class, and a medal, for “short women with no appreciable muscle tone.” And, with respect to children, there’s a lot of sorting out, and the poor runners and the uncoordinated ones just end up with other activities, so long as they’re not encouraged to continue as a way to overcome a disability.

Semenya’s defenders say, “so what if she has high testosterone levels; we don’t declare Michael Phelps ineligible because he has abnormally-large feet.” But in Semenya’s case we’re talking about a difference which cuts at the dividing line between “men” and “women” as relevant for competitive sporting purposes. Sure, we could place the dividing line differently, and say that anyone who doesn’t have the complete set of advantages that a “natural” man has — including, say, a man with naturally low testosterone levels — may race in the women’s category, but that creates a situation in which some competitors have too great an advantage over others in the class.

And fundamentally, we like to tell and hear stories of sports heroes who work hard and who succeed due to their efforts, rather than by this sort of difference that places them at a borderline spot in their category.

image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACaster_Semenya_London_2012.jpg; By Tab59 from Düsseldorf, Allemagne [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons