Plural.

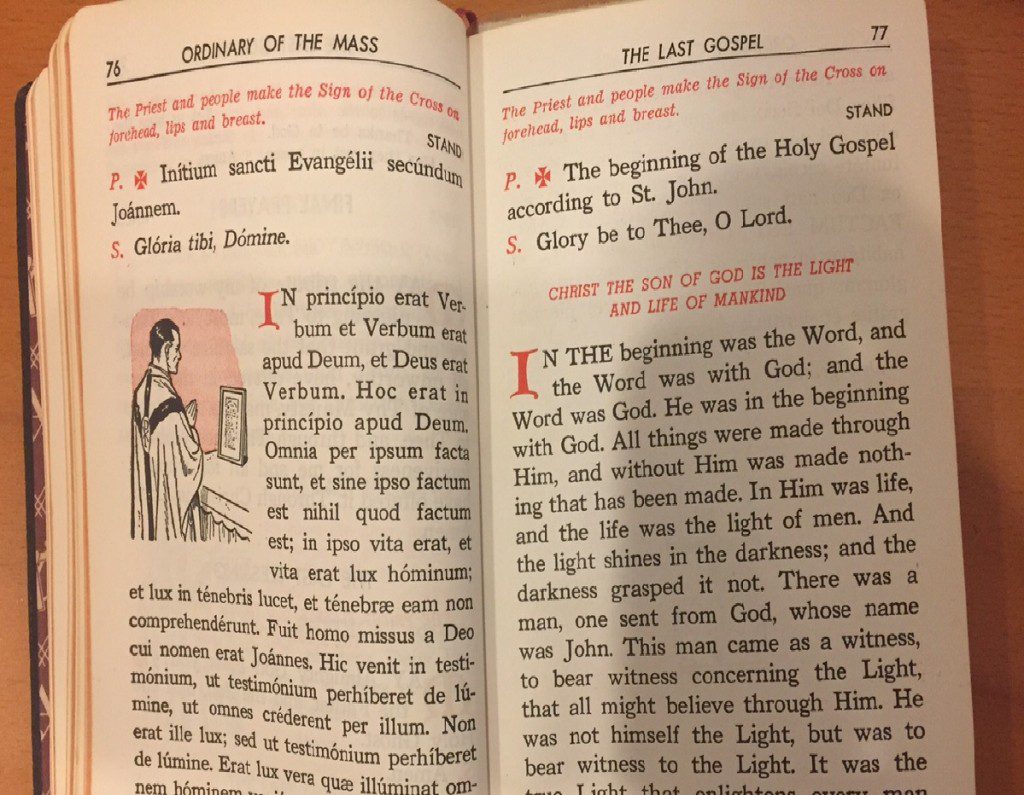

Some years ago, I attended Catholic mass on Christmas Day for the first time, and learned that the readings are not the standard nativity narrative you hear on Christmas Eve, but are instead the opening to John:

In the beginning was the Word,

and the Word was with God,

and the Word was God.

He was in the beginning with God.

All things came to be through him,

and without him nothing came to be.

What came to be through him was life,

and this life was the light of the human race;

the light shines in the darkness,

and the darkness has not overcome it.

The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world.

He was in the world,

and the world came to be through him,

but the world did not know him.

He came to what was his own,

but his own people did not accept him.But to those who did accept him

he gave power to become children of God,

to those who believe in his name,

who were born not by natural generation

nor by human choice nor by a man’s decision

but of God.

And the Word became flesh

and made his dwelling among us,

and we saw his glory,

the glory as of the Father’s only Son,

full of grace and truth.

This was, once upon a time, the “Last Gospel,” read every Sunday at the close of mass, prior to the Vatican II re-write. And the priest who preached on this talked about what a profound concept the Incarnation is — that the distance between God and man is inconceivably vast (e.g., human vs. a bug), yet bridged with Christ.

This is no mere matter of God giving humanity a “gift” — it’s far deeper than that. It’s not a matter of God looking down on humanity and thinking, “I think I’ll give them a present.” And to say, “we give each other gifts because God gave us the gift of Jesus” — if you think about it, it seems more a rationalization of the gift-giving tradition than a real explanation of the origin of the tradition.

The “real meaning” of Christmas? I dunno. Seems like, from a religious perspective, the feeling Christmas should inspire is simply to be in awe.

But the secular version of Christmas? A year ago, I observed that, shorn of any belief that Christ is indeed the Son of God, this meaning is simply impossible to hold.

At the same time, reflecting a bit more, there is a genuinely meaningful “true meaning” to the secular celebration of Christmas.

Not “peace on Earth” — Christmas really has nothing to do with peace except for the statement of the angels. “Peace” isn’t a fundamental part of the Christmas story, nor in the wider Christian story — after all, Jesus himself says that he did not come to bring peace, but a sword. And Christmas is certainly not the story of refugees or immigrants or the homeless, and anyone who takes the nativity narratives as proof that we should admit more refugees into the United States, or open our borders to more unskilled immigrants, or provide an amnesty for those already here, is trying to score political points that just don’t belong to a religious holiday. And don’t get me started on warm-and-fuzzy messages of “hope in the darkness” — do people really find that meaningful? Do people really find that message in Christmas celebrations, and feel a renewed sense of hope in their lives?

But the Santa Claus story? There is within this a “true meaning” — the celebration of the virtue of generosity. Behind the chaos of buying presents for children (and the demands of said children), and trying to find a satisfactory present for family, friends, and sometimes bare acquaintances, there is an underlying expression of the idea that giving to others is important, not just in a reciprocal fashion, but to help the less fortunate and to share from our plenty.

In fact, the Santa Claus story, and the idea that we should “be Santa” to others, fits in with this “Christmas meaning” a heck of a lot more than with the Incarnation.

And this “Christmas means generosity” — well, you can easily transform this into “December means generosity” or consider Christmas a cultural celebration of generosity, without necessarily any connection to Christ except for the origin of the holiday, and non-Christians, by virtue of living in a country with the national “culture” of Christmas, can share in the celebration of generosity.

But “celebrate generosity” and the Incarnation are two different things entirely, and the latter meaning is disappearing except, of course, for Christmas Day mass. How should we respond? Do we abandon Christmas as a celebration of the Incarnation, and move that to the feast of the Annunciation instead?

Readers, your thoughts?