Not this:

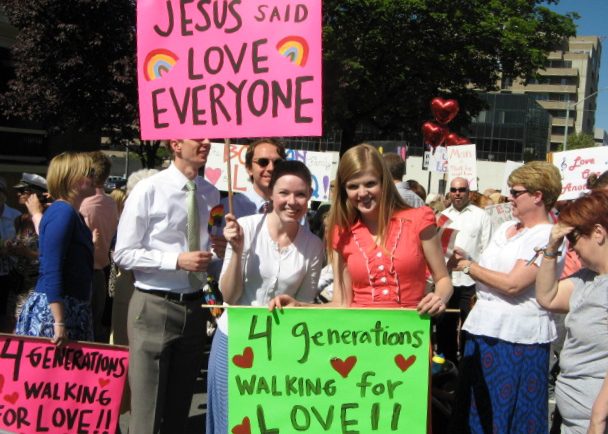

![https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ATrump-WomensMarch_2017-top-1510075_(32409710246).jpg; By Mark Dixon from Pittsburgh, PA (Trump-WomensMarch_2017-top-1510075) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/533/2017/01/Trump-WomensMarch_2017-top-1510075_32409710246.jpg)

according to a couple recent articles that passed through my twitter feed recently.

Tablet published a piece by Lee Smith titled, “The Arab-ization of American Politics“, with a provocative subtitle: “Why do so many Americans mistake what typically signals a failure of democracy for democracy itself?”

The crux of Smith’s argument is this: despite the protesters’ chant that “this is what democracy looks like” that we hear repeatedly at these marches,

American democracy is not about the size of crowds. Mass gatherings are not supposed to guide our democracy or protect our freedoms. Yes, the Constitution guarantees the right to freedom of assembly as well as freedom of speech, as it also guarantees, for instance, the right to bear arms. However, only a fool believes that democracy looks like collecting Nazi-era Lugers, or looks like a closet full of pornographic magazines. The actual mechanism of democracy is not people going to the street, but to the ballot box and voting for their chosen candidate.

The Founding Fathers did not need the example of the French Revolution birthed in blood and gore the same year the U.S. Constitution came into force in order to understand the dangers of people going to the streets to fight for their political ideas. The violence that frequently results—whether ignited by the most radical protesters, or by the most radical protectors of order—when political power is counted in large numbers massed in public squares is a constant throughout human history. And that’s exactly what the framers sought to save us from.

In fact, Smith says, mass crowds generally represent, e.g., in the Arab Spring, the failure of democracy — Westerners took it for granted that the protesters against Mubarak in Tahir Square were pro-democracy because they equated protests with democracy, so they were unprepared for the Morsi government to embrace the Islamism of the Muslim Brotherhood; and subsequently, they were unprepared for the return of authoritarianism in al-Sisi because, after all, he came to power due to yet more protesters.

A second article, in City Journal, by Steven Malanga, “The Book of Saul,” addresses the particular question of the Democratic party. Referencing proclamations of success of the “Women’s March” and the actual substantial advantages of the GOP at the state and national level, he writes:

The new Democratic Party—the one increasingly governed by identity politics and driven by special interests—has become so intoxicated by the nostrums of Saul Alinsky and his “Rules for Radicals” that it has forgotten how to operate in a democracy, where elections count more than revolutionary theater. Perhaps this is the inevitable result of elevating a charismatic former community organizer to the presidency. President Obama was a gifted campaign strategist and an appealing personality, but he convinced his party that the Alinsky model was a viable permanent approach to governing. True, it often worked for him, but success led him to use it as a crutch, even after he assumed the world’s most powerful office. “We’re going to speak truth to power,” presidential advisor Valerie Jarrett once said when asked about media bias against Obama’s policies. As political scientist Pete Peterson pointed out, however, “[Y]ou’re the White House. You are the power.”

Obama inspired a generation of like-minded Democrats to follow him into the protest-as-politics movement. Bill de Blasio has been an elected official in New York City for 15 years now, having served on the city council and as public advocate, and now as mayor. Yet, he attends protests as if he were a powerless outsider and occasionally “invites arrest,” according to the New York Times. In a city dominated by left-leaning Democrats, getting arrested on purpose is good politics.

So what is the value of protests in a modern, functioning democracy?

Last week we saw generically anti-Trump protests. On Friday, the March for Life took place. And this weekend, there were various protests at airports in reaction to individuals being detained and prevented from entering the United States despite previously-obtained visas or even permanent residency.

At the same time, flying across my facebook feed are calls to call Congressmen about the upcoming confirmation vote for Betsy DeVos — and yet these facebook posts struggle with the question: what do you do if you know your Senators are firmly on one side or the other? One friend, in Michigan, hoped that there would be value in calling Senators in Ohio with the pitch that “we have family and friends in Ohio” but it seems to me that offices simply don’t give the time of day to callers who aren’t constituents.

And of course, the increasing focus on battleground states and early-primary states has meant that many people feel keenly the irrelevance of their vote, and the uselessness of traditional activities like knocking on doors and passing out flyers.

Readers, thoughts? Are protests the cornerstone of democracy or one step away from mob rule?

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ATrump-WomensMarch_2017-top-1510075_(32409710246).jpg; By Mark Dixon from Pittsburgh, PA (Trump-WomensMarch_2017-top-1510075) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons