Perhaps you remember this from history class in school: in the system of slavery as it existed in the American South, it was illegal to teach a slave to read or write.

The State systematically denied slaves the ability to gain an education, because they believed that the ability to read and write would enable slaves to fight against their oppression. It could be said that their human right to an education was being denied them, though it’s a trivial observation when their basic human right to liberty of person was denied.

But is there a universal human right to be provided with an education? A right to have someone else, with suitable qualifications, give you instruction, whether in basic literacy or numeracy, or multivariate calculus? And a right to be provided, by someone else, with the relevant supplies, and classroom space that’s heated as necessary, and desks and equipment? And a right to have one’s living expenses provided for, if an adult, while engaging in this process?

No.

To be sure, various state constitutions claim to be guaranteeing such a right, as do the constitutions of other countries. But what they are doing is not a matter of a pledge to respect universal human rights. What they are doing is creating an entitlement, defining an obligation of the state and committing themselves to meet this entitlement — no differently than the pledges of the old Soviet Union constitution to a “right” to work, to housing, to “rest and leisure” and so on, all of which were subject to the demands of the state. For instance, the “right to work” carried with it the explicit caveat that the right to choose one’s occupation was subject to the “needs of the state.” (This comes from an old, old blog post of mine, from shortly after I started blogging, and either the links didn’t convert to the Patheos system properly or I neglected to link.)

And I agree that it’s appropriate for the government to take on this obligation — though I would dispute claims that it is the federal government in particular that has the obligation to provide this education, or that the government has the obligation to ensure that, however much education any individual want, be made available to them. Not only are there practical reasons to provide a free public education — our entire society would suffer if children were dependent on their parents’ willingness to pay the needed sums of money or ability to find charitable schools– but it is simply part of what government is about, to provide for the common good.

But that’s not because it’s a “human right.”

“Human rights violators” are countries in which the government imprisons or otherwise punishes people for seeking to speak out, practice their religion, assemble together, publish and share written works, or even for being a family member of such a person. They are countries that actively oppress ethnic or religious minorities by denying access that they make available to others, restricting their ability to earn a living, taking away their rights to property, restricting their access to redress in the justice system, and through other means, including imprisonment, or indifference to others who attack them.

To declare education to be a “human right” means to call every state that provides its citizenry with a (perceived) inadequate level of education a “human rights violator.”

Now, you might say that I’m just quibbling, and that there is a general consensus that “human right” can also mean “thing which the State has the responsibility to provide for.” The state has the responsibility to ensure, insofar as it is possible, that its people do not starve, that they are not exposed to the elements due to lack of shelter, that they have provision for healthcare. In modern terminology, you might say, these are simply labelled as the “right to food, right to housing, right to healthcare” – the so-called “positive human rights” as distinguished from the traditional (negative) human rights which have to do with things the government may not do. No big deal.

But it does matter.

Even Eric Zorn, Chicago Tribune columnist and single-payer supporter, gets it. His column today argues that, in the same way as basic education is a “right,” so, too, is healthcare — or, rather, that’s the claim implied in the headline, “If basic education is a ‘right,’ why not basic health care?” but the text itself is more moderate that that, writing that

That the U.S. is not among those countries [enshrining healthcare as a “constitutional right”] either shouldn’t prevent us from aiming to provide a basic level of health care for all.

Because there is civic and economic value in a healthy population.

Because we know that it requires far fewer resources in the long run when we catch and treat chronic conditions early.

Because we know that it’s a moral abomination that the unluckiest among us face bankruptcy, death or both when medically stricken.

And because we know that, to paraphrase UNESCO, good health is essential for the exercise of all other human rights. . . .

It may be, however, that fightin’ words are impeding that progress. Arguing for health care as a right seems to harden the resolve of those who get hung up on semantics.

Better to argue that expanding Medicare-like protections to everyone is a responsibility. Providing quality health care is an obligation to our fellow man. It’s a joint investment in our shared future, that, like our joint investment in education, will benefit us all.

Debates about “rights” take us to dead-ends. Debates about responsibilities of governments, and responsibilities of us all to our fellow man — these get us somewhere. How do we, as a society, collectively, act to ensure that people without means have their basic material needs met when they’re unable to do so for themselves? How do we, in general, balance the need for individual human responsibility, with the fact that it’s better for people to get their cavities filled than become toothless? How far do these responsibilities extend — to sameness of provision or the minimal meeting of needs?

And, beyond this, how should our economic system be structured, to give people the best chance of providing for their needs? It seems to me that focusing on “rights” of people to receive basic provision take us in the wrong direction on this question — because they presume direct state provision, in all cases, and disasters like Venezuela.

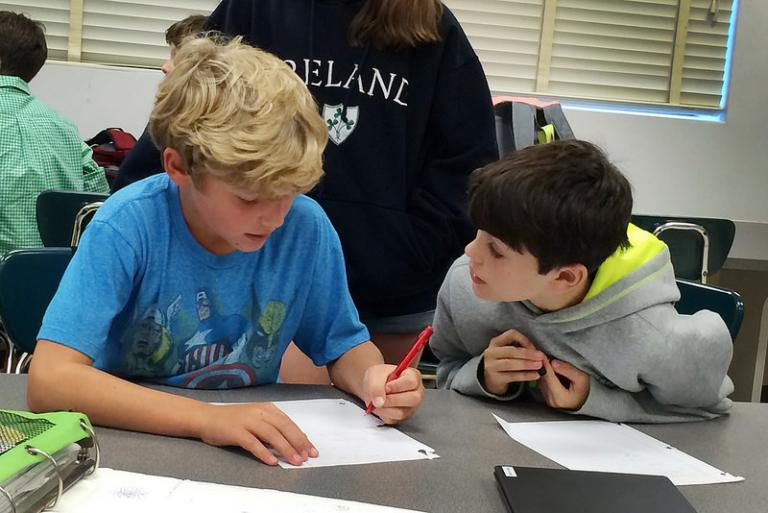

Image: children in a classroom. from flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/wwworks/15344079560; by woodleywonderworks; Creative Commons license.