This, from the New York Times, “A Family-Friendly Policy That’s Friendliest to Male Professors,” which reports on the impact of the standard accommodation for new parents among professors seeking tenure: stopping the clock; that is, allowing additional time beyond the usual seven years after hire.

This policy is apparently generally applied rather blindly; all such new parents receive this benefit, regardless of whether they take leave time, put the baby in daycare right away, etc. This policy became the norm at universities in the late 90s/early 2000s, though 1/5th of universities did not adopt such policies. The Times then reports,

Three economists — Heather Antecol, a professor at Claremont McKenna College, Kelly Bedard, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Jenna Stearns, a doctoral student at Santa Barbara — evaluated these gender-neutral tenure-extension policies in important new research.

The policies led to a 19 percentage-point rise in the probability that a male economist would earn tenure at his first job. In contrast, women’s chances of gaining tenure fell by 22 percentage points. Before the arrival of tenure extension, a little less than 30 percent of both women and men at these institutions gained tenure at their first jobs. The decline for women is therefore very large. It suggests that the new policies made it extraordinarily rare for female economists to clear the tenure hurdle.

So it’s easy to understand why men’s success increased — they used the extra time to publish more, while being disadvantaged minimally or not at all by the new baby, to the extent that their wives were stay-at-home-moms or, even if not, they continued to work long hours, with the baby in daycare or in bed. (The article takes it for granted that male academics are disproportionately likely to have SAH-wives, which seems unlikely to me, as I would expect it would be more the norm that they’d have been working to support the husband during grad school days, but I suppose I’m not an expert.) Oddly, the disadvantage that the women face isn’t cited in terms of being busy caring for a baby — that is, if they’d taken a significant maternity leave — but instead other factors:

Perhaps this reflects the physical toll of pregnancy, the difficulties of a complicated birth, the extra task of nursing or simply an unwillingness to shirk parenting duties.

But why would women be disadvantaged, rather than simply less-advantaged than men? Because, the authors report, the extra year than men get raises tenure committee expectations for achievements during the tenure-seeking span, and women who defer research, or decrease their productivity, during this period of pregnancy/childbirth/childbirth-recovery/early-infancy childcare, fall short of these increased expectations.

The article itself mentions the policy at the University of Michigan as being different, and, indeed, it is.

To begin with, as required by law, the university provides 12 weeks of unpaid leave for FMLA reasons, and faculty may request further unpaid leave for child care and other “personal circumstances.”

In addition, for each “event that adds a child or children to his or her family,” a faculty member is entitled to one term of “modified duties,” which means, in general, that one is not required to teach, only conduct research, advise doctoral students, and other responsibilities. But in an effort to be “fair,” they add another provision: One must take

significant and sustained care-giving responsibility for the child (or children) during the period for which modified duties are requested as a single parent or, where there are two parents, that is at least as time-consuming as the care-giving responsibility of the faculty member’s spouse or partner.

In other words, single parents are eligible, as well a parent whose spouse is working, but not someone with a stay-at-home spouse. I suppose one is eligible if one’s spouse works part-time, if the “modified duties” are also considered to be a sort of temporary part-time work. Presumably if both spouses are working, the university doesn’t further demand some proof as to which party picks the baby up from daycare, has primary weekend care-giving responsibility, etc.

But this isn’t yet “stopping the clock.” There’s another piece, though:

In recognition of the effects that pregnancy, childbirth, and related medical conditions can have upon the time and energy a woman can devote to her professional responsibilities, and thus on her ability to work at the pace or level expected to achieve tenure, a woman who bears one or more children during her tenure probationary period shall, upon written request to the relevant dean (in the case of the UM-Dearborn and UM-Flint campuses, the relevant provost) be granted an exclusion of one year for each event from the countable years of service that constitute the tenure probationary period to a maximum of two years.

So, one year automatic upon giving birth. In addition, there are up to two years (additional, I think) of extension available for child care needs, subject, again, to the tenure candidate not having a stay-at-home spouse.

So I can understand the logic here, but it’s regrettable. It says something like this:

We expect tenure-seeking professors to work far in excess of 40 hours per week in order to publish a sufficient amount. We further expect that men with stay-at-home wives will continue to work these overtime-hours even after their children are born, so they don’t need accommodating. But those without stay-at-home spouses should be enabled to work a “normal” work week at least temporarily so as to be able to pick the baby up from daycare on time.

But all of this misses the fundamental problem: the concept of tenure in the first place — a fixed period of time in which to “prove oneself” in competition with other faculty, by publishing a sufficient number of publications, of a sufficient quality level, for the prize of guaranteed employment. And, oooh boy, am I glad I took a different path.

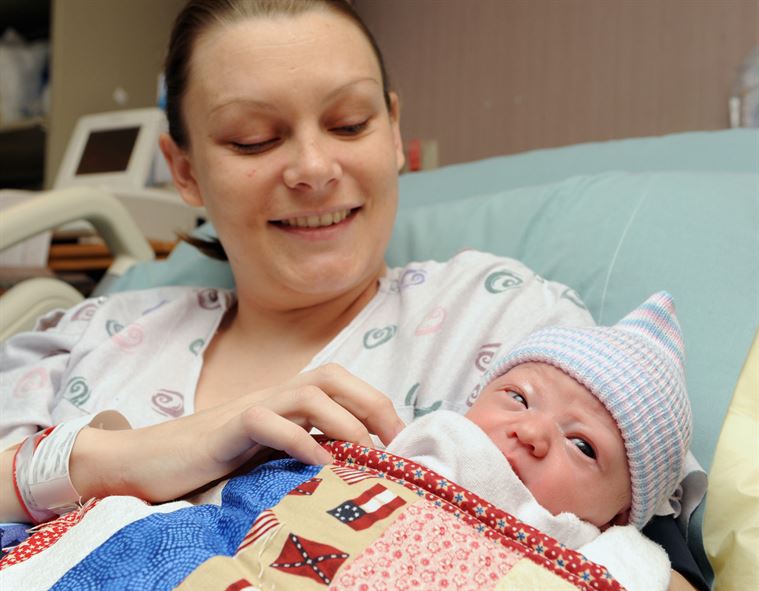

Image: http://www.mountainhome.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2000602500/ (public domain; US gov’t photograph)