![Dresden, Teilansicht des zerstörten Stadtzentrums über die Elbe nach der Neustadt. In der Bildmitte der Neumarkt und die Ruine der Frauenkirche. Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1994-041-07 / Unknown / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/533/2017/01/Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1994-041-07_Dresden_zerst%C3%B6rtes_Stadtzentrum.jpg)

(Warning! Spoilers ahead!)

I tried.

My kids, the high-schooler and the incoming high-schooler, brought home a couple of the books from which they could choose for their summer reading list. One of them, All the Light We Cannot See, by Anthony Doerr, historical fiction around World War II, sounded interesting, so I started reading. And it has racked up some major awards, and 26,838 reviews on Amazon, with an average 4.6 out of 5 stars. So it’s a Good Book, right?

Now, I’m going to start by admitting that I’m a bit of a dunce when it comes to the “lyrical prose” that reviewers of such books rave about. I simply don’t get enchanted by these sorts of descriptions. And the storytelling device the author chooses, of starting at the War’s end when the characters were in their mid-teens, then backtraking to their early childhood, didn’t really do anything for me.

But that’s not what bugged me.

The story traces the lives of two main characters, Marie-Laure, a blind French girl, and Werner, a German Ruhrpott orphan.

Marie-Laure’s father is the locksmith for the Paris natural history museum, and as the occupation begins, he and Marie-Laure flee to his uncle’s home on the coast, with an enormously large and valuable diamond entrusted to him that carries with it a myth that whoever owns it will never die while those around him suffer untimely deaths. The father begins to map out and measure the city in order to construct a model for Marie-Laure, so that she can learn to navigate it, but just after he finishes, he is imprisoned (suspected of sabotage) and sent to a prison camp. Subsequently, Marie-Laure, the uncle, and the housekeeper begin working with the resistance, broadcasting coded messages from a radio transmitter in the attic of the 6-story house.

Simultaneously, Werner grows up in the orphanage, using his mechanical skills to rebuild a radio found in the trash, and then using the radio to broaden his universe, first by, in the early Nazi period, listening with his sister to broadcasts of all kinds, including the broadcasts of a Frenchman they call “The Professor,” about science (he knows French because the woman who runs the orphanage is French), and then listening to forbidden reports of the war itself. He is called on to fix the radio of a German military officer’s family, and, his genius observed, invited to a military academy, saving him from a fate of coal-mining, where he experiences the abuse of those institutions but is also mentored by a teacher in whose lab he works at nights. He subsequently angers that teacher, who takes his revenge by claiming that the boy’s birth certificate was falsifed, he really is 18, not 16, and sending him to the front, where he works to identify radio transmissions of partisans.

Marie-Laure and Werner’s paths cross when he ends up in France, assigned to find the source of the radio transmissions which turn out to be those of Marie-Laure’s uncle; Werner realizes that the sender is the “professor” from his childhood, decides to claim he cannot find this transmission, and ends up rescuing her instead, at precisely that instant when she is otherwise about to be killed by the German officer who has come to find the diamond, seeking it out because he is dying of cancer and he hopes it would save his life.

So far, so good, right? Well, if you can buy the idea that Werner by sheer coincidence ends up assigned to track down the individual responsible for science broadcasts he listened to as a child, and likewise by coincidence rescues her at exactly that instant when her life is directly in danger. And there was a whole bit that I didn’t quite follow in which he and a fellow soldier were trapped in a basement, buried below rubble, for a week or so. Early on, they discuss whether they could use a grenade to dislodge the rubble that keeps them from leaving the basement, but the older soldier says, “no, it’ll kill us.” Then — I suppose because he figures that they’ll die either way, so the risk is worth it — out of nowhere he tosses the grenade, and, a page later, they’re out.

Honestly, some parts of the book felt a bit hazy to me. Rather than painting a crystal-clear picture of what was going on, it was that sort of “I think I can get the gist of it” as when I read German (which I ought to resume, as I’m not sure if I could manage it as well as I could have a decade ago). The device of switching back and forth in the time periods contributed to this feeling of haziness, and, look, I’m not a dumb person.

But here’s what left me feeling irritated with the book, in the end: there’s enough death and destruction in the world. I don’t need to get invested in fictional characters, only to have them die or suffer, not to advance the plot but seemingly, well, “just because.”

Werner escapes any pitched battles due to his position in the army; he only sees the dead bodies of partisans afterwards, when he’s told to gather up the equipment they were using for whatever value it might hold. He only once sees a shooting, when they’re in an apartment where they think there is a hidden transmitter, and a jumpy nervous soldier shoots a child who was hiding in a closet, who he thought was a partisan. But he contracts some unknown illness that means that, at the conclusion of the book, when he is a POW in an infirmary, unable to keep any food down, he delusionally walks into a minefield. Boom! Dead. For no particular reason.

His younger sister, who shared The Professor’s broadcasts with him and was angry with him when he destroyed the radio, for fear that it’d be discovered, who wrote letters to him expressing such fears about the war that the reader is shown only the “censored” versions, stays at the orphanage, until, in the last pages of the book, we learn that the orphanage has been emptied out of small children, and she and the older girls and the director are moved to Berlin to work in a factory there, and are subsequently raped by Soviet soldiers. There was no reason for this — it didn’t further the narrative, and I certainly have never read of, in real life, girls and women being moved into Berlin. My best guess is that the author wanted to work the Soviet rapes into the story in some fashion.

And Werner’s best friend at the academy, an upper-middle class boy who is there because he’s “supposed” to be, but actually loves birds more than anything else, is weak and slow, and is also severely nearsighted but has to hide the fact, is bullied and beaten to such a degree that he ends up back at home — and severely brain damaged, unable to care for himself in any way. The author makes sure to let us know that, even years later, in an epilogue, he never recovered and only ever endlessly scribbles on paper, day after day.

Maire-Laure, at least, has a happy ending — almost too happy, as if to make up for the fates of the others — as she becomes highly-educated, teaches and works at the museum, and has a child and then a grandchild. And her uncle, too, who had been a recluse after World War I, traveled with her after the war ended.

So in the end, yes, I stayed up late at night to finish it, but in a “let me just get to the end so I can know what happens” sort of way, not “this is so magnificent I never want it to end.” And now I think I’ve had my dose of fiction for a while, or at least of prize-winning fiction. Maybe I’ll see if any of the Star Trek novels my oldest son was reading before leaving on their trip, are still around.

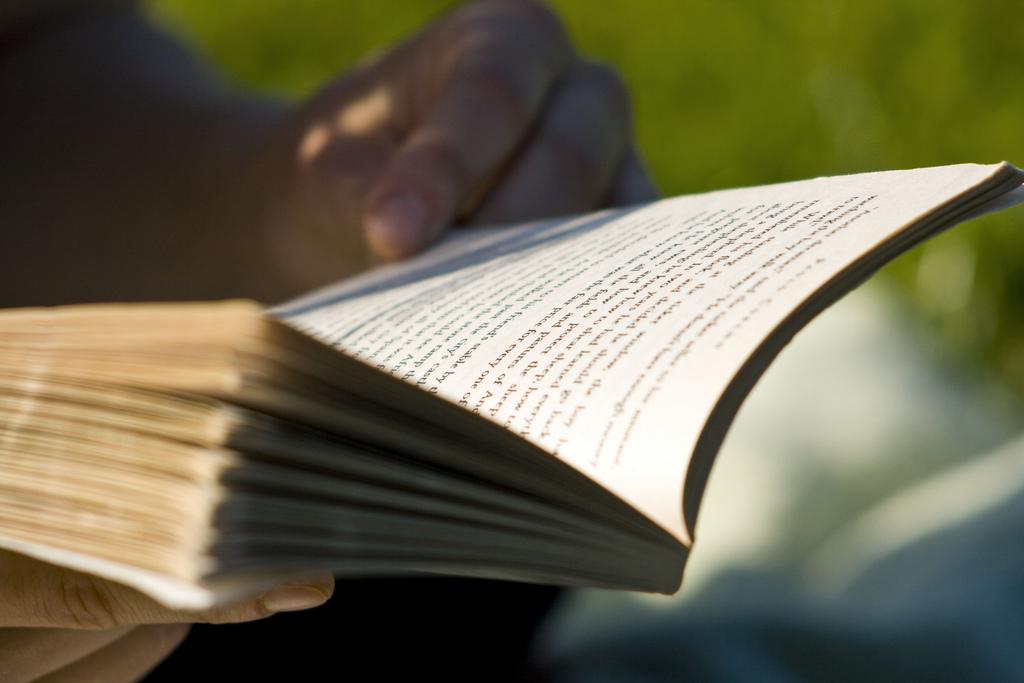

Image: OK, this is Dresden, not the town in which this book takes place. But, eh, World War II.

Dresden, Teilansicht des zerstörten Stadtzentrums über die Elbe nach der Neustadt. In der Bildmitte der Neumarkt und die Ruine der Frauenkirche. Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1994-041-07 / Unknown / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons